After approving necessary water permits for the Northeast Supply Enhancement (NESE) pipeline, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection is considering air permits for a related 32,000-horsepower compressor station in Somerset County’s Franklin Township in the face of intense community opposition.

The proposed pipeline, twice rejected by New Jersey and New York, has reemerged as the Trump administration embraces “energy independence” built upon unfettered oil and gas development. The NESE project would extend the Williams Cos.’ Transcontinental natural gas pipeline system from Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, through New Jersey and beneath the Raritan and Lower New York Bays to Queens in New York City.

A Williams subsidiary, the Transcontinental Gas Pipe Line Company LLC, known as Transco, has argued that the project is necessary to meet growing demand in New York City and Long Island, describing it as critical for energy resilience and regional economic growth.

Environmentalists and Franklin Township residents say they don’t understand why New Jersey regulators now seem to support the pipeline after rejecting it in 2019 and 2020, arguing that the project would threaten renewable energy goals, endanger fragile coastal ecosystems and pollute the air and water.

After NJDEP approved the NESE water permits on Nov. 7, multiple environmental nonprofits filed lawsuits less than two weeks later, arguing that the agency had “unjustifiably” authorized permits that were previously rejected.

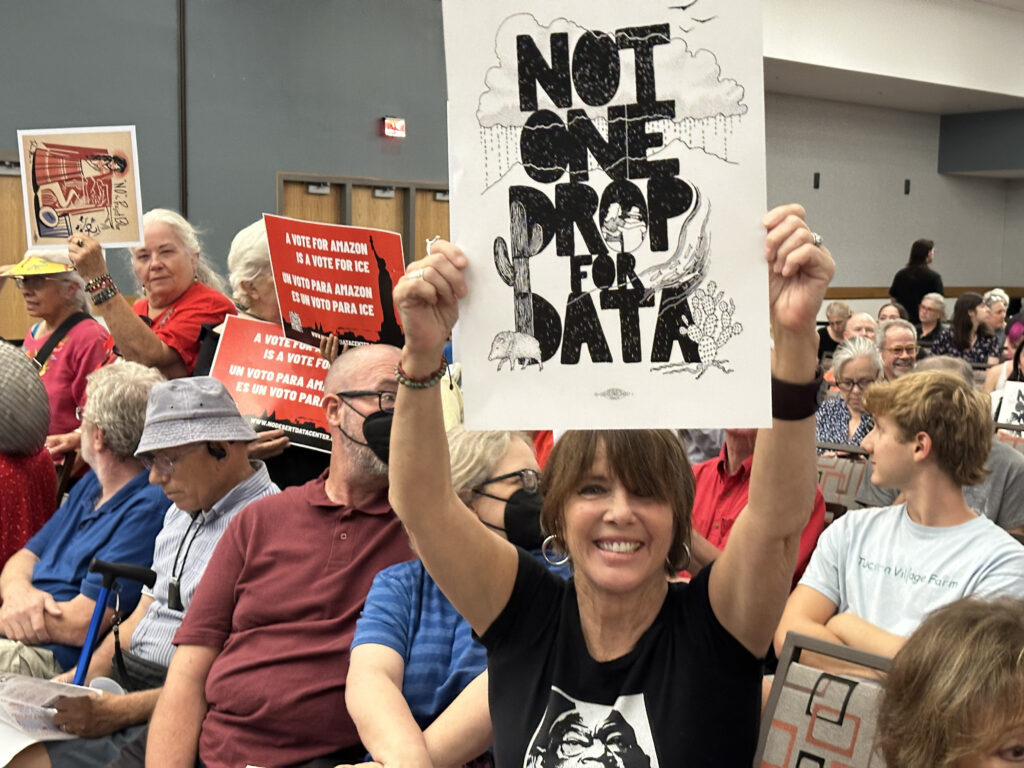

When NJDEP held a public hearing on the air permits for the compressor station on Nov. 13, many of those testifying began by expressing their confusion and frustration with the approval of the water permits, arguing that nothing had changed since the prior rejection.

One after another, residents from Princeton Manor, a 55-and-older community in Kendall Park, New Jersey, less than two miles from the possible compressor station site, took turns lambasting the project.

“The seniors in my community range in age from 55 to 103 years old, and many of them are frail,” said Rupali Chakravarti, a Princeton Manor resident. “In a one-and-a-half-mile radius, there are 2,000 homes and three schools with 600 kids. So 6,000 or more New Jerseyans will have to breathe the toxic air all day, every day.”

Transco officials did not respond to requests for comment.

Multiple Princeton Manor residents asked the NJDEP officers overseeing the virtual hearing how they plan to protect citizens’ health and whether they would want their elderly grandparents to live so close to a natural gas compressor station.

Compressor stations are a crucial component of a pipeline system, boosting pressure at multiple points along a lengthy pipeline to ensure the flow of natural gas. The Environmental Protection Agency conducted a national inspection and maintenance effort for compressor stations in January 2021, finding that about 1,790 compressor stations support more than 279,000 miles of interstate natural gas transmission pipelines.

Natural gas compressor stations have a significant negative impact on local communities’ air quality, emitting volatile organic compounds. Studies prepared by college professors in the Virginia Scientist-Community Interface show that compressor stations significantly impact local air quality by emitting volatile organic compounds.

Poor air quality can contribute to a slew of short-term health problems, including headaches, nausea and irritation of the mucous membranes and long-term health risks such as increased mortality rates, lung cancer risk and cardiovascular and respiratory diseases.

A few years ago, Franklin Township Mayor Philip Kramer had 20 air quality monitors placed around his town and found that the worst readings were almost always near I-287. He said the natural gas compressor would produce as much pollution as 3,200 cars annually on the highway.

Franklin Township has been fighting the construction of the compressor station since 2016. The township council formed an ad hoc committee, the Franklin Township Task Force, in 2017 to inform the public of the health and safety issues related to the pipeline extension.

“At this time, it just seems a bit harder,” Kramer told Inside Climate News, describing the “maddening” experience of fighting against the project multiple times. “What has changed? This was bad before, and it was acknowledged to be bad, and it’s still bad. And my town will suffer and get no benefit whatsoever from it, so it’s frustrating,” he said.

The mayor also said that he met with Transco representatives several months ago before any of the virtual permit hearings. When he asked whether the compressor could be electrically powered, he said they told him it would place a burden on their customers. Kramer said he took their response as the company saying they would not make as big a profit utilizing an electric-powered station compared to a methane-powered one.

Besides mentioning concerns about living near the compressor station, many of those testifying against the pipeline’s air permits said they did not even mention blowdowns, which are controlled releases of pressurized natural gas from compressor stations during emergencies or scheduled maintenance. Blowdowns can last from a few minutes to several hours and can cause significant air and noise pollution.

“You cannot leave a community with the uncertainty of what’s going to happen with the blowdowns,” Anjuli Ramos-Buscot, the director of the Sierra Club’s New Jersey chapter, said in an interview.

Ramos-Buscot said she reviewed the documents that Transco submitted to the NJDEP and found that their failure to mention blowdowns was a “huge mistake.” She said it’s possible that blowdowns would not happen in Franklin Township. But because there was no information in the permit applications regarding blowdowns, she said, it’s not clear where they might happen.

Ramos-Buscot also said that there are no precautions residents can take when a blowdown occurs, except staying inside.

NJDEP lacks the authority to regulate the harmful emission leakage that could happen at a compressor station, near the station or any spot along a pipeline, Ramos-Buscot said. She said her biggest concern with the compressor station and pipeline involves emissions of benzene and formaldehyde, both known carcinogens, from pipeline leakage and blowdowns at compressor stations.

“That is one of the biggest weaknesses that we have in terms of regulating air quality in the state and in the country, it’s that we’re really not assessing the real problem with pipelines,” Ramos-Buscot said.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,