PECOS COUNTY, Texas – Sharon Wilson trained her bulky, black camera on a thin, steel tower next to a natural gas compression station.

The screen of her Optical Gas Imaging camera lit up with warm colors, indicating that methane was pouring out of the tower.

Wilson, of the non-profit Oilfield Witness, was recording the Oklahoma-based company ONEOK’s Coyanosa station in its WesTex pipeline network. The station maintains pipeline pressure of natural gas during transportation.

Wilson documented widespread flaring, venting and other methane releases during a week in the Texas Permian Basin this month. Natural gas prices in the Permian Basin fell below zero during March. When natural gas prices are low, companies are more likely to vent or flare methane. Pipeline capacity to transport the gas out of the Permian Basin is currently limited, which can also result in more flaring.

We’re hiring!

Please take a look at the new openings in our newsroom.

See jobs

That’s bad news for efforts to fight climate change. Natural gas is mostly made up of methane and the Permian Basin is the single-largest source of methane emissions in the U.S. oil and gas industry. As a greenhouse gas, methane is about 80 times more potent at warming the atmosphere than carbon dioxide over a 20-year period.

Flaring also releases a variety of hazardous air pollutants, including volatile organic compounds like benzene, a carcinogen, and contributes to ground-level ozone, a pollutant that causes respiratory illness and heart disease.

The Permian Basin produces more crude oil than any other in North America and is now the second-most productive gas basin in the country. Drilling for oil yields the biggest profits for energy companies, but oil drilling also produces large volumes of natural gas. Companies flare natural gas if they aren’t able to sell or transport it, a practice known as routine flaring.

“They have to get rid of the gas because it’s going to cost them money to get it in a pipeline,” Wilson said.

At the Waha Hub, where natural gas produced in the Permian Basin is funneled into pipelines to reach demand centers, the price for gas dipped below zero on March 13 and was still negative as of March 21. Analysts warn that the capacity for pipelines to transport gas away from the Permian Basin is limited.

The ONEOK compression station where Wilson documented methane emissions connects gas producing wells in the Permian Basin to the Waha Hub.

An ONEOK spokesperson said during the time period Wilson documented emissions at the compression station, “no unpermitted emissions occurred.” However, a spokesperson for the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality said the emissions were not reported to their agency, as required by law, and they would be looking into the incident.

Price of Gas Key to Methane Question in the Permian Basin

The Permian Basin sprawls across the arid landscape of West Texas and southeastern New Mexico. The quantity of this gas in the Permian has nearly tripled since 2018, according to the Energy Information Administration.

At drilling sites, the Railroad Commission of Texas enforces State Rule 32, which prohibits flaring natural gas. However, the Commission grants thousands of exceptions a year. Companies can request an exemption to flare when there is not enough pipeline capacity. During January 2024 in Texas, 2.65 percent of the natural gas produced at oil wells, known as casinghead gas, was flared, according to information provided by the Railroad Commission. More recent data was not available.

“In the rush to develop the oil in the area, [companies] don’t plan for how to manage the gas that’s produced at the well,” explained Elizabeth Lieberknecht, a regulatory and legislative manager at the Environmental Defense Fund.

The Environmental Protection Agency issued its final rule to reduce methane emissions under the Clean Air Act in December. The new rules, as written, will eventually prohibit routine flaring, which is currently allowed in Texas. However, the attorneys general of Texas and another two dozen states have challenged the federal rule. The legal challenges may delay implementation.

Extensive pipeline construction has facilitated moving natural gas out of the Permian. But East Daley Analytics, which provides energy market analysis, and Validere, an emissions data company, projected in a May 2023 report that, starting in 2024, production growth in the Permian Basin once again could exceed gas “takeaway” capacity. The authors expected the problem to peak in mid-2024. When there is not enough pipeline capacity, companies can either limit drilling or increase flaring.

The report’s authors wrote that some companies “will likely opt to flare” instead of waiting to drill wells while pipeline capacity is limited. An East Daley representative said the company has not updated its analysis since the May 2023 report and could not comment further.

Joshua Rhodes, a research scientist at the University of Texas, Austin, said there is a “perfect storm” creating a glut of gas in the Permian. He pointed to a mild winter that drove down demand for gas. Meanwhile renewables in the region like solar and wind are producing well. Several pipelines are currently undergoing maintenance in the region, further constraining capacity.

While the United States exported record volumes of liquified natural gas during 2023, demand in the European market is flattening. Natural gas consumption in Europe fell to a 10-year low in 2023.

“The problem is that oil demand is still high,” he said. “That’s what’s continuing the production of natural gas.”

The Energy Information Administration reported that the price of natural gas at the Waha Hub fell to -$0.25/MMBtu on March 13. The price remained negative the subsequent week, dropping as low as -$1.16/MMBtu on March 18. In areas like Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale, which is dominated by natural gas, drillers are dialing back. But in the Permian Basin, where oil is the most lucrative commodity, drillers still added rigs, the large drilling sites, during March. These drillers will continue to produce natural gas alongside the oil, despite the drop in prices and pipeline capacity problems.

EDF’s Lieberknecht said the impacts of price fluctuations on flaring show that voluntary commitments from oil and gas companies are not enough. She said the federal methane rule will level the playing field and, eventually, phase out routine flaring and require drillers to capture the gas instead.

“We think that’s a huge step forward, especially in Texas where we don’t have any meaningful regulation requiring operators to do that,” she said.

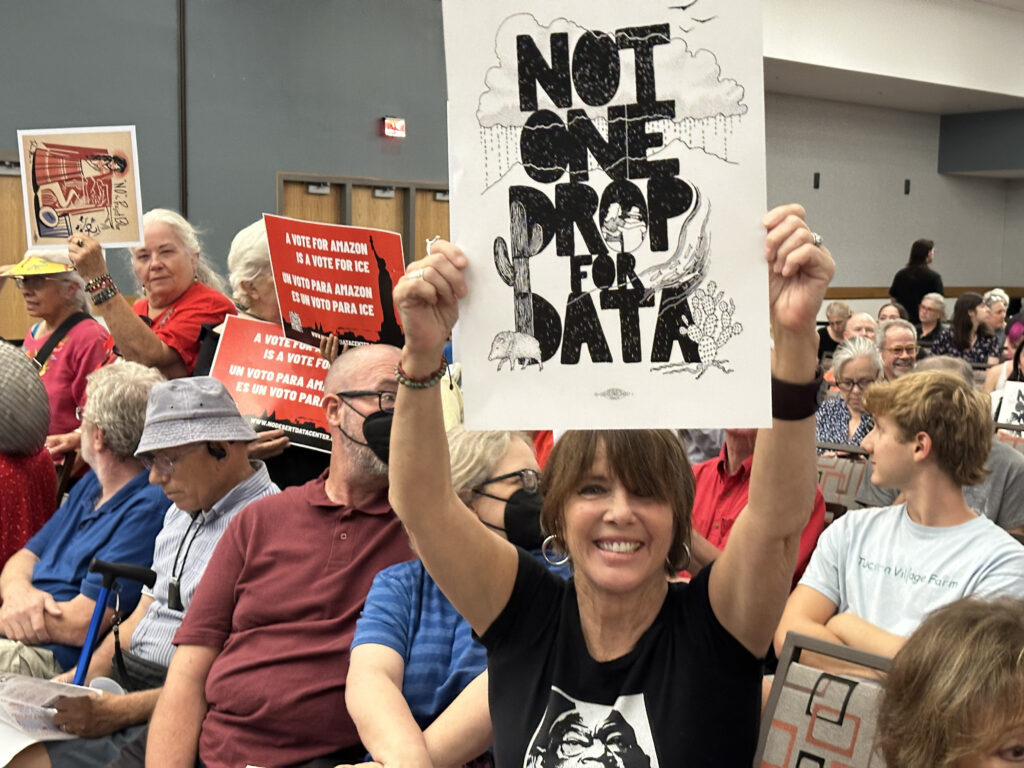

Grassroots Emissions Tracking Continues

Wilson, with her Optical Gas Imaging camera, is accustomed to seeing rampant methane emissions while “ground truthing” in the Permian Basin. But she said the negative natural gas price appeared to be contributing to increased emissions during her recent field work.

“It’s not just flaring, we saw numerous blowdowns, we saw really intense tank emissions,” she said. Blowdowns occur when gasses are released at wells or pipelines to reduce pressure and are even worse for the climate than flaring. “There are emissions everywhere.”

Wilson said measuring emissions on-site is important to capture methane releases that companies do not report to regulators. Her previous work has documented that the majority of flares go unreported.

“We saw just an unbelievable amount of emissions that would not have been detected if we weren’t out there,” she said.

In Texas, the Railroad Commission and the TCEQ split jurisdiction over emissions from oil and gas drilling, processing and refining.

Railroad Commission spokesperson Patty Ramon said applications to flare undergo a “thorough” review. However, records in the state flaring query database indicate that the Railroad Commission has approved 1,077 applications to flare since Jan. 1, 2024, and denied one application.

The elected leaders of the Railroad Commission have been critical of the federal methane rule. Commissioner Wayne Christian has called the regulations “more bureaucratic red tape stifling business.”

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

The TCEQ regulates air emissions from other stages of the oil and gas supply chain, including processing plants and refineries. A TCEQ spokesperson said that companies must report any emissions events within 24 hours.

The Department of Energy has also awarded $134 million to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality for plugging low-producing wells to reduce methane emissions. The spokesperson said the agency is working with the Department of Energy to finalize the program for the funding.

In New Mexico, the New Mexico Energy, Minerals and Natural Resources Department’s Oil Conservation Division enforces the state’s methane flaring regulations. Spokesperson Sidney Hill said the agency is “generally aware” of the potential impact of natural gas prices on operations. The state’s rules prohibit flaring when there is limited pipeline capacity.

“Just because prices are low does not mean routine flaring will be permitted,” he said.