Fracking’s Forever Problem: Seventh in a series about the gas industry’s radioactive waste.

When John Quigley became the secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection in 2015, he knew that he would be busy trying to keep up with the consequences of the state’s rapid increase in natural gas production. But when reports landed on his desk that trucks carrying oil and gas waste were tripping radioactivity alarms at landfills, he was especially concerned.

“There was obviously a problem that the state was not dealing with,” Quigley said. “Which was the threat to not only public health, but to the folks driving the trucks and people handling the waste in the oil and gas industry. They were unnecessarily put at risk.”

Ten years after the alarms first unsettled Quigley, fracking in Pennsylvania has continued to grow, generating huge volumes of oil and gas waste and wastewater in the process. Seventy-two percent of the solid waste ends up in landfills within state borders, and a truck carrying it sets off a radioactivity alarm every day on average, an Inside Climate News analysis found.

Radioactive elements such as radium, uranium and thorium in rocks deep underground come to the surface as a byproduct of oil and gas drilling. Experts have long worried about the potential health and environmental impacts of this waste. Radium exposure is linked to an increased risk for cancer, anemia and cataracts.

New research from the University of Pittsburgh suggests that the wastewater created by fracking the Marcellus formation, the ancient gas deposit beneath Pennsylvania, is far more radioactive than previously understood. And there is also evidence that some of it is getting into the environment: Researchers have found radioactive sediment downstream from some landfills’ and wastewater treatment plants’ outfalls.

But the state has barely shifted its approach to regulating the waste. “Nothing material has been done,” said Quigley, who left in 2016. “Nothing has really changed.”

In 2023, radioactivity alarms were triggered more than 550 times at Pennsylvania landfills because of oil and gas waste, according to an analysis of landfills’ annual operations reports conducted by Inside Climate News. The vast majority of this waste was disposed of on-site; landfills rejected the waste only 11 times. Radium-226 was the most common isotope cited as the reason for the alarm.

DEP issued a new guidance document for solid waste facilities and well operators that handle radioactive materials in 2022, with some of the changes specifically aimed at the fracking industry. Landfills have been required to submit a Radiation Protection Action Plan to the state since 2001, covering protocols for worker safety, monitoring and detection and records and reporting, and DEP may require sites to test regularly for the long-lasting radium-226 and radium-228 if they have received large volumes of radioactive oil and gas waste.

But DEP has fallen behind on many other aspects of regulating this waste.

In 2021, then-Gov. Tom Wolf said the state would require regular radium testing of landfills’ leachate, a liquid byproduct created when rainwater passes through waste, accumulating contamination. Wolf’s announcement came more than five years after DEP had recommended adding radium to leachate testing requirements. But leachate testing results from 2021 through 2024 acquired by Inside Climate News via a right-to-know request do not contain results for radium.

In an email, DEP spokesperson Neil Shader said the agency does not currently require landfills to test for it. He did not explain why the policy has not yet been implemented.

“DEP is still finalizing a policy around radiological material in leachate,” he said.

Understanding the scope of the problem is difficult because Pennsylvania’s tracking of oil and gas waste and leachate remains disorganized and piecemeal, an Inside Climate News investigation found. Landfills are supposed to turn away waste that is too radioactive based on the total volume of waste they have already accepted that quarter. If the volume estimates are inaccurate or misreported, it could mean that some sites are exceeding the allowable amounts.

Meanwhile, DEP’s last comprehensive study of radioactivity in oil and gas waste is more than nine years old, even though the agency said at the time that follow-up investigations were needed. DEP confirmed to Inside Climate News that it is studying the radioactivity of landfill leachate but offered no timeline for publication.

The Marcellus Shale Coalition, an industry trade group, maintains that the solid waste and wastewater generated by fracking in Pennsylvania is well managed and poses no health risks to the public or workers. Landfill employees face less danger from oil and gas waste than someone getting a routine CT scan, the group argues, and landfill permits contain restrictions on how much oil and gas waste they can accept in any given year.

In a statement to Inside Climate News, the coalition’s Patrick Henderson said there’s “no greater priority” for the industry “than worker and community safety, which is delivered through recurrent trainings, development and sharing of best practices, and strict adherence to modern regulatory standards.”

“Operators follow stringent protocols for handling, managing, and transporting waste—including radioactive screening, characterization, and reporting,” he said.

The industry also frequently notes that DEP’s 2016 investigation into radioactivity in oil and gas waste concluded that there is “little or limited potential for radiation exposure to workers and the public” from natural gas development.

Quigley called this study, the initial version of which was published just before he took office as DEP secretary, “the big mistake,” because in his view it falsely suggested that there was “nothing to worry about.”

He thought that another study was warranted to investigate the true scope of the issue, but he said he wasn’t able to push forward a new one before he left office.

The study was limited in some ways by its size and distribution: between 2013 and 2014, DEP sampled 38 well sites, only one in the northeast, which researchers now say is a radioactivity hotspot. Sixteen of the sampled sites were in the southwest.

Read More

Tracking Oil and Gas Waste in Pennsylvania Is Still a ‘Logistical Mess’

By Kiley Bense, Peter Aldhous

David Allard was the lead health physicist overseeing the study’s design and execution. He retired from DEP in 2022 after 23 years as the director of the Bureau of Radiation Protection, where he oversaw the management of radioactivity in the oil and gas industry. In 2001, he fought for the radiation protection plans and radioactivity monitoring at landfills that are required today.

These rules and Pennsylvania’s rules for landfills in general are stricter than most other states’, he said. Ohio, for instance, stopped requiring landfills to report on the oil and gas waste they accept.

Scientists learned about the radioactivity of oil and gas fields more than a century ago, not long after the discovery of radium in 1898. Waste predating the fracking era had been triggering radiation alarms in Pennsylvania landfills for years.

But the waste created by fracking is different from conventional drilling wastes. In the 2010s, as fracking increased oil and gas waste volumes, Allard wanted to investigate how radioactive it was and what possible dangers it might pose to the public and the environment.

The 2016 study concluded that the radioactivity levels found in the waste at the time posed little danger to truck drivers and workers. But it warned of potential radiological risks to the environment from spills, waste treatment facilities and long-term disposal in landfills, a point that is often overlooked in summaries of the study’s contents. All of these things remain a problem today, Allard said.

“I fought very hard to get this thing going,” he said of the study. “I will stand behind all of the science.” But he said that one of the reviewers, a political appointee, had argued for language in the synopsis that he felt obscured the nuances of the study’s conclusions: “little or limited potential for radiation exposure.”

“It’s a true statement. But I think it did downplay the need for additional work,” he said. Variations of this phrase appear at the beginning of each bullet point in the summary. Each one is followed by caveats.

DEP used computer modeling from Argonne National Laboratory to determine whether a closed landfill that had accepted this waste and other toxic material would still be dangerous to a farmer living on the site far into the future. Even 1,000 years from now, DEP found, a farmer digging a drinking well on top of such a site would not want to drink the water.

“It’s not going to be pretty,” Allard said. “It’s not going to be very palatable.”

Pennsylvania’s guidance for how much radioactive oil and gas waste a landfill can accept each year, updated a few years into the fracking boom in the 2010s, is supposed to prevent the hypothetical future farmer from being exposed to harmful levels of radiation. But this guidance isn’t codified into law, Allard said. It also relies on regular radioactivity monitoring and accurate tracking of waste quantities at landfills.

Recent research from Penn State and the University of Pittsburgh showing that radium is getting into the environment also concerned him. These radioactive discharges into waterways are unregulated, he said.

“I think the EPA really needs to stand up,” he added. In 2020, Allard was part of a committee formed by the National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements that highlighted the need for national, standardized regulations for oil and gas waste because the rules are so inconsistent among states.

Road-spreading, the practice of using salty oil and gas wastewater as a dust suppressant, is another area where he says the study could have done more to figure out how much radioactivity was ending up in the environment as a result. Although the state has largely banned the practice, there is evidence that companies continue it.

Landfills’ leachate also deserves more study, he said, and he sees testing it for radium and releasing the results to the public as an important step.

“We tried to make it as comprehensive as possible,” Allard said of the study. “But I think it is timely to go back and visit some of these things.”

Environmentalists have long clamored for an updated government study of radioactivity in oil and gas waste using more recent data. Pennsylvania’s fracking industry is much larger and more geographically dispersed now than it was when the information for the first study was collected.

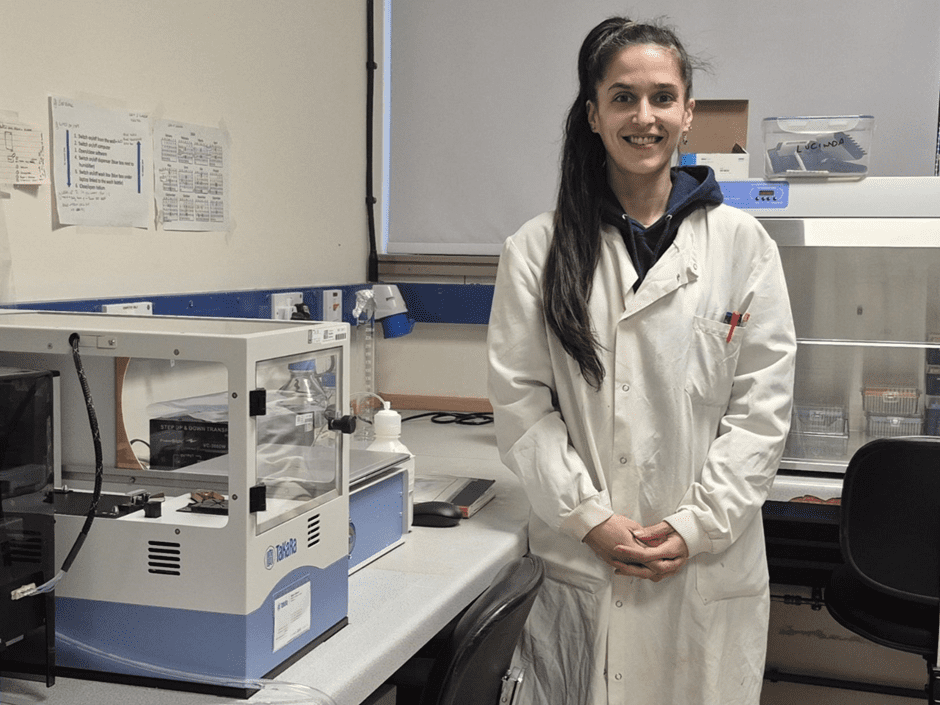

Forthcoming University of Pittsburgh research suggesting that oil and gas wastewater produced by fracking in Pennsylvania is more radioactive than previously thought involved samples from 561 well pads between 2012 and 2023. The wastewater contained much more radium than was found by studies early in the fracking boom.

The median radium values were four times the level of those published by the U.S. Geological Survey in 2011 and twice that of DEP’s findings in 2016, said Daniel Bain, an associate professor of geology and environmental science at the University of Pittsburgh who was involved in the research.

The maximum value that Bain found was above 41,000 picocuries per liter—a measure of radioactivity in a substance. For comparison, the EPA’s limit on total radium in drinking water is 5 picocuries per liter.

Radium is a naturally occurring material, and surface and groundwater can contain between 0.01 and 25 picocuries per liter. Natural levels above 50 picocuries per liter are rare.

“I think it necessitates a reevaluation of the kind of personal protection that specific jobs require. If you’re in contact with this waste every day, you need to be monitored,” Bain said. “They probably also have to rethink how they’re going to manage their waste streams.”

Bain’s research also found that radioactivity was far higher in the Marcellus formation’s wastewater than in wastewater from drilling in other parts of the country, including Texas and North Dakota.

He said that the finding echoes earlier industry realizations that the Marcellus is different from other natural gas formations. “One of the first hard lessons of the Marcellus was that it’s not like some of the Texas shales. They came up here and tried to use the methods they used in Texas, and they had issues,” he said. “They’re basically learning as they’re doing. It’s a big experiment, and sometimes you wish you could redo the experiment.”

Marcellus wastewater has higher than expected levels of barium, strontium and lithium, a discovery that spurred industry interest in 2024 because of lithium’s status as a critical mineral.

Wells in the northeastern part of Pennsylvania contained much higher concentrations of radium than others, suggesting that earlier conclusions based on drilling in the state’s southwestern region might be misleading.

Bain’s research did not focus on the radioactivity of solid oil and gas waste, the lion’s share of what Pennsylvania landfills take from the industry. But he did look at what kind of waste would be created if companies were to start treating Marcellus water with the goal of removing valuable components like lithium.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

His analysis found that this process could create a solid, highly radioactive byproduct that would exceed U.S. Department of Transportation transport limits for radium in sludge. Although questions remain about the financial viability of extracting lithium from fracking wastewater, at least one company in Pennsylvania has already tried to do so.

In 2021, environmentalists were heartened when Wolf announced that landfills would be required to test their leachate for radium and report the results to the state quarterly. The new requirement would “improve public confidence that public drinking water and our precious natural resources are being appropriately protected,” Wolf said at the time.

Josh Shapiro, now governor and then attorney general, commended Wolf’s announcement, which came after Shapiro’s office had “urged Governor Wolf to direct DEP to prevent harmful radioactive materials from entering Pennsylvania waterways.”

“The improved monitoring and promised analysis by DEP is a step in the right direction,” Shapiro said at the time. Other states with active fracking, including North Dakota, West Virginia and Colorado, require this kind of leachate testing.

John Stolz, a professor at Duquesne University who has studied oil and gas waste and fracking contamination for years, said he was “very disappointed” that DEP was still not requiring this testing or releasing it to the public.

“We were told they were going to start monitoring for these additional parameters, and it just hasn’t happened,” he said.

Stolz would like DEP to go beyond radium and require testing at landfills for other oil and gas-related substances that could help scientists better trace fracking’s impact, such as lithium, strontium and bromide. “They’re still only monitoring parameters that you would monitor if you were looking at a discharge from, say, a wastewater treatment facility,” he said.

Bain, who has collaborated with Stolz on research, said he has tried without success to get DEP to rethink the issue of its testing requirements missing many key indicators for fracking.

“If you don’t look, you don’t see,” he said. “This is really something that DEP should be doing.”

The radium levels Stolz has discovered in testing landfill leachate are relatively low, but not when considering the millions of gallons of leachate produced every year. “That’s a lot of radium,” Stolz said. “It doesn’t seem like a lot [at first], but then you realize the volumes involved, right? It’s a huge amount of water going on for years and decades.”

Radium’s tendency to be “sticky” and to accumulate—in stream sediment, for example—could create problems over the long-term for the environment and for public health, Stolz said.

Those most at risk from this radioactivity are the workers at landfills, wells and treatment facilities that handle and transport large quantities of oil and gas waste. “The levels can be high,” said Sheldon Landsberger, a professor in nuclear and radiation engineering at the University of Texas at Austin who has studied the radioactivity of oil and gas waste. “I would not say that they are dangerous levels, to the tune of Chernobyl or Fukushima or anything like that. However, if you are a worker and you do work in the field, you need to be monitored.”

Landsberger reviewed records from Pennsylvania landfills that showed radioactivity measurements for truckloads of oil and gas waste coming in and for workers exposed to those shipments. “They are definitely above background,” he said, though none of the measurements are above the legal limits for radiation exposure.

Landsberger said it was hard to deduce much from the records about long-term impacts because there are too many unknowns about how the measurements were taken and what happened to the waste after it was disposed of in the landfill. This is why he advocates for workers wearing radiation dosimeters, which measure the radiation dose that a person receives.

Jack Kruell lives a quarter-mile south of the Westmoreland Sanitary Landfill in Belle Vernon, a site in the southwestern part of the state that has taken hundreds of thousands of tons of oil and gas waste over the years. Stolz’s testing of the landfill’s leachate in 2019 showed that it was consistent with contamination from oil and gas operations and that it had elevated levels of radium-226, radium-228 and bromide, all likely linked to the landfill’s acceptance of that waste. (Westmoreland did not respond to requests for comment.)

In 2012, when the fracking boom was well underway, Kruell noticed strange smells in the air. “The odors were so horrific, and it was constant. I did some work for one of the oil and gas exploration companies, and I was familiar with smells, and this was not a normal landfill smell,” he said.

Over the next few years, he experienced medical symptoms he hadn’t before: fatigue, bone pain, respiratory reactions, mental fog. As the odors worsened, he avoided going outside. Later, when he got involved with advocating for changes at the landfill, Kruell learned about something that alarmed him even more: the radioactivity in the landfill’s liquid waste.

“When you look at the half-life of radium-226, it’s 1,600 years,” Kruell said. “This is never going to go away.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,