In the early 2000s, the Peruvian government granted a Canadian silver mining company a license to begin exploratory operations in Indigenous Aymara territories. The project divided communities, with some worrying about potentially devastating impacts on the ecosystems they relied on for sustenance and with which their culture was entwined.

While the company, Bear Creek, engaged some locals, those talks proved inadequate. Communications were largely in Spanish while most people spoke their native Aymara language. Meeting locations couldn’t accommodate all participants and a requirement that locals submit their concerns in writing presented an obstacle for people whose culture is primarily oral.

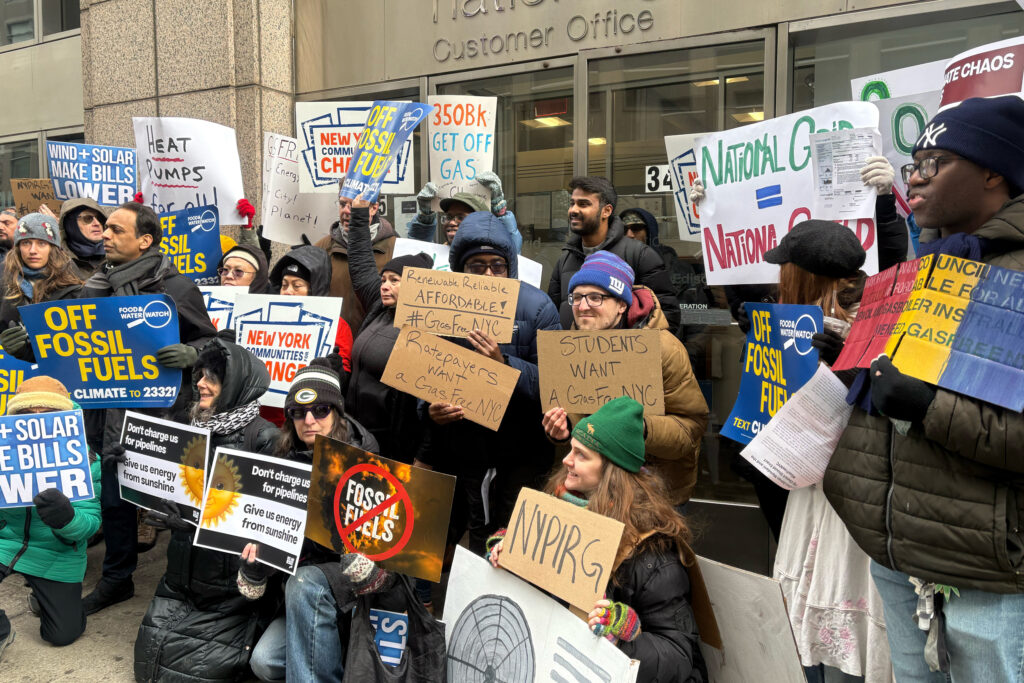

By 2011, thousands of Aymara people who opposed the project had organized in resistance. They wrote letters demanding the company cease operating, and blockaded roads, chanting “Water yes, mining no!” The regional government of Puno issued an ordinance banning mining.

We’re hiring!

Please take a look at the new openings in our newsroom.

See jobs

As tensions reached an apex, locals clashed violently with police, leaving at least five people dead while injuring hundreds of others. To restore order, the Peruvian government in June 2011 revoked a key permit, effectively shuttering Bear Creek’s operations.

What might have been the end of the saga turned out to be the beginning of the next chapter. In 2014, Bear Creek sued the Peruvian government for $522 million plus legal costs, a sum derived not only from the company’s actual investments but also expected future profits.

That Bear Creek could claim such an enormous amount is thanks to an international legal system known as investor-state dispute settlement, or ISDS, that has rewarded foreign investors with more than $100 billion to date. In some cases, investors have won cases even when leaving the ecosystems where they operated awash in toxic pollution or after being linked to human rights abuses carried out against locals.

The ISDS system, embedded into the Canada-Peru free trade agreement and thousands of other treaties, provides special rights to foreign investors and gives those investors access to ad hoc tribunals where they can sue governments in proceedings that often take place behind closed doors in far away places like the World Bank headquarters in Washington.

A growing number of legal scholars, economists, labor leaders and environmental and human rights advocates have been calling on governments to reform or do away with this system, arguing that it tramples on human rights and is an obstacle to climate action. Perhaps the most glaring injustice, many of these advocates say, is the disproportionate impact of the ISDS system on Indigenous peoples, an issue highlighted by a report released Thursday by Public Citizen, a consumer advocacy group.

The report highlights the extensive disparities in access to justice between the foreign investors who finance mines, oil fields and other operations in Latin America and the roughly 50 million Indigenous people who live throughout the region, often in the territories targeted by those corporations for their natural resources. Ultimately, the report argues, “ISDS and the rights of Indigenous peoples are inevitably at odds.”

No Right to Participate

ISDS was designed as an exclusive dispute resolution system between foreign investors and governments.

“The system isn’t made for communities to be involved,” said Carla García Zendejas, director of the People, Land and Resources program at the Center for International Environmental Law, a legal advocacy group based in Washington.

Speaking at a panel in Washington tied to the launch of the Public Citizen report on Thursday, García Zendejas said arbitration proceedings often take place thousands of miles from affected communities and provide little if any access to relevant documents. Participation requires highly technical knowledge of investment law, and for communities is generally limited to the filing of amicus briefs that can have little bearing on the proceedings, “and in many cases, they don’t allow you to do that.”

In Mexico, after a U.S. mining company sued the government over the rejection of a deep-ocean mining permit, a fishing cooperative tried to submit an amicus brief but was denied the opportunity by the tribunal, which said the cooperative did not have “a significant interest in this dispute.”

Local communities in Guatemala were similarly barred from participating in an ISDS suit launched by Canadian mining company KCA. They accused the company of attacking peaceful protestors with “beatings, tear gas and arrests,” Public Citizen said.

Even when arbitrators have been open to amicus briefs, it is often advocacy groups who submit them, and those groups may not have the authority to speak for Indigenous communities or align with their interests.

In ISDS cases where Indigenous rights play a central role in disputes, arbitrators have no authority to enforce those rights and have been unwilling to hold investors accountable for their violation.

In Bear Creek v. Peru, there was evidence that the company’s behavior ran afoul of international standards for consulting Indigenous peoples, such as offering economic benefits to some but not others and treating different Aymara communities inconsistently. The company also failed to address communities’ concerns about the project or to grapple with basic tenets of Aymara culture, according to tribunal records.

An expert witness at the arbitration proceedings, which were held at World Bank headquarters in Washington, said “Bear Creek did not understand the Aymaras and they did not understand their communal relations…. If Bear Creek had understood how to work properly with the communities—with the Aymara communities, the social conflict would not have reached crisis levels as we saw in the region.”

Still, the ISDS tribunal awarded Bear Creek $18 million and did not penalize the company for its treatment of the Indigenous communities, which had a direct impact on the collapse of the mining project.

Disparate Enforcement of Rights

Like foreign investors, Indigenous peoples have rights under international law.

Treaties like the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and International Labor Organization Convention 169 (the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention) recognize communities’ rights to be consulted about projects that affect them and to participate in the use and management of resources on their territories.

But, there is a yawning gap between the enforceability of transnational companies’ rights and the rights of Indigenous peoples.

While investors can side-step national court systems, going straight to ISDS tribunals, Indigenous groups with rights-violation claims against governments must generally slog through rounds of appeals before ultimately being permitted to file a petition with international human rights courts.

Throughout that process, Indigenous communities, which are often based in remote areas, need to overcome barriers such as finding legal counsel and coming up with thousands or millions of dollars necessary to fund such litigation.

If they’re able to last the years, or even decades, that it often takes to “exhaust domestic remedies” and win an international court judgment against their government, there is no enforcement arm to compel governments to comply with the rulings.

By contrast, foreign investors with ISDS judgments can stalk governments around the world, seizing the state’s foreign-held assets and making it a pariah in global financial markets.

If Indigenous communities want to take legal action against foreign companies that affect them, the process is equally as daunting.

When Ecuadorians living in the country’s Amazon region attempted to sue the U.S.-headquartered Texaco, and later its successor Chevron, in American courts over extensive oil-related pollution, it took them nearly a decade of litigation just to be told that their claims had nothing to do with the United States, and another decade to learn that, because of the fraudulent acts of their own lawyers (which the locals did not condone or have knowledge of) they would be prevented from seeking recovery for their extensive injuries.

Chevron, it turned out, went on to win not one, but two ISDS lawsuits against the Ecuadorian government connected to its operations. In 2016, it was awarded $112 million in the first ISDS case and is awaiting the final amount of the judgment it won in the second suit. That number is expected to be in the hundreds of millions or billions of dollars. Chevron’s pollution in the Ecuadorian Amazon has yet to be remediated, and Ecuadorians harmed have received no compensation.

Donald Moncayo, an Ecuadorian activist and president of the Union of People Affected by Texaco, who called in to the panel in Washington on Thursday from Ecuador via Zoom, said his campesino community was never invited to take part in the ISDS cases, despite the fact that their rulings had direct impacts on their community and their ability to collect damages related to the pollution.

“We want to live with dignity,” Moncayo said. “I don’t like being called a sacrifice zone because I live in a place with oil extraction. My life doesn’t have a price.”

Turning Governments Against Citizens

Governments staring down enormous fiscal consequences of ISDS lawsuits often have little incentive to fulfill their obligations to Indigenous communities, or to make regulatory decisions that protect those communities’ interests.

The culprit, according to the report, is the rampant use of the ISDS system by companies that have pushed its boundaries from challenging nationalizations and expropriations to claiming that the enactment of more stringent environmental policies amount to “regulatory takings” of their investments.

This evolution has resulted in a widespread understanding that governments are being threatened with the prospect of ISDS suits for proposing new regulations.

If governments don’t yield to the interests of investors, the consequences can be costly—going beyond compensating investors for what they’ve spent and requiring them to pay future expected earnings based on speculative formulas.

When Colombia sought to establish a National Park in part of the Amazon rainforest, U.S. and Canadian mining companies sued the government for more than $27 billion. The country was hit with another suit from Canadian companies for more than $800 million for the government’s creation of an environmental protection area in a high-mountain region. Both protected areas benefited Indigenous communities who rely on those areas’ resources and consider parts of the ecosystems sacred, the report says.

These tremendous awards often divert spending away from social and environmental programs, too, with downstream impacts on Indigenous communities who often benefit from those programs.

Public Citizen noted the case of Peru, which has nearly 10 million people living in poverty. The country is currently facing 18 pending ISDS cases, with just seven of those cases potentially costing the government over $2.2 billion—the foreign investors in the remaining 11 cases haven’t disclosed the sums they are seeking. That $2.2 billion could cover the country’s costs for a range of services from water sanitation, forestry, social investment, education, health and housing, according to the report.

Environmental and Human Rights Law Compliance

Many Indigenous communities’ cultures and livelihoods are closely connected and interdependent with their territories, meaning pollution and other forms of environmental degradation caused by foreign investors’ operations have an outsized impact.

A long-standing principle of international environmental law is that the “polluter pays.” But the ISDS system has flipped that rule on its head, forcing governments to pay polluting companies.

Investors have little incentive to engage in meaningful consultation processes with Indigenous communities or to strictly abide by the same environmental protection standards they are bound to in their home countries, which are often more stringent.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

The investment treaties that give rise to ISDS only place obligations on governments while bestowing rights on investors. Foreign companies typically only need to meet the environmental regulations of the state where they are operating, and often those rules aren’t strictly enforced and penalties aren’t costly enough to drive a change in companies’ behavior.

When Indigenous and other local inhabitants of Ecuador’s Intag Valley resisted the Canadian mining company Copper Mesa’s operations, the company hired paramilitary groups that used violent force against the locals. When, in response, Ecuador revoked the companies’ operating license, Copper Mesa initiated an ISDS suit, ultimately winning $26.5 million in a case that excluded the affected communities’ participation.

The Public Citizen report recommends that governments remove ISDS from their investment treaties, or alternatively, incorporate Indigenous rights into those agreements, such as the right to participate in ISDS proceedings and mandating that foreign investors obtain consent from Indigenous peoples on projects that impact them.