Once a month for nearly two years, Evan Clark, the Waterkeeper at Three Rivers Waterkeeper, a water quality advocacy organization based in Pittsburgh, has traveled by boat along the Ohio River to Shell’s enormous new plastics plant in Beaver County.

This facility is a cracker plant, using ethane from fracked gas to make ethylene and ultimately to manufacture up to 1.6 million tons of plastic per year. In his boat, Clark looks for tiny plastic pellets called nurdles and monitors the plant’s outfalls, the places where its wastewater is discharged into the river.

Since the plant became operational in the fall of 2022, Clark has noticed strong chemical odors at the outfalls—potentially a sign of contaminants like volatile organic compounds, or VOCs—and found many, many nurdles, a feedstock used to make everything from soda bottles to car parts.

This winter, Clark and the team he works with at the Mountain Watershed Association collected samples from 11 square feet of soil from the Ohio’s shorelines both upstream and downstream of the plant. Three Rivers Waterkeeper works to protect the Allegheny, Monongahela and Ohio Rivers, while the Mountain Watershed Association focuses on protecting the Youghiogheny River, a tributary of the Monongahela.

We’re hiring!

Please take a look at the new openings in our newsroom.

See jobs

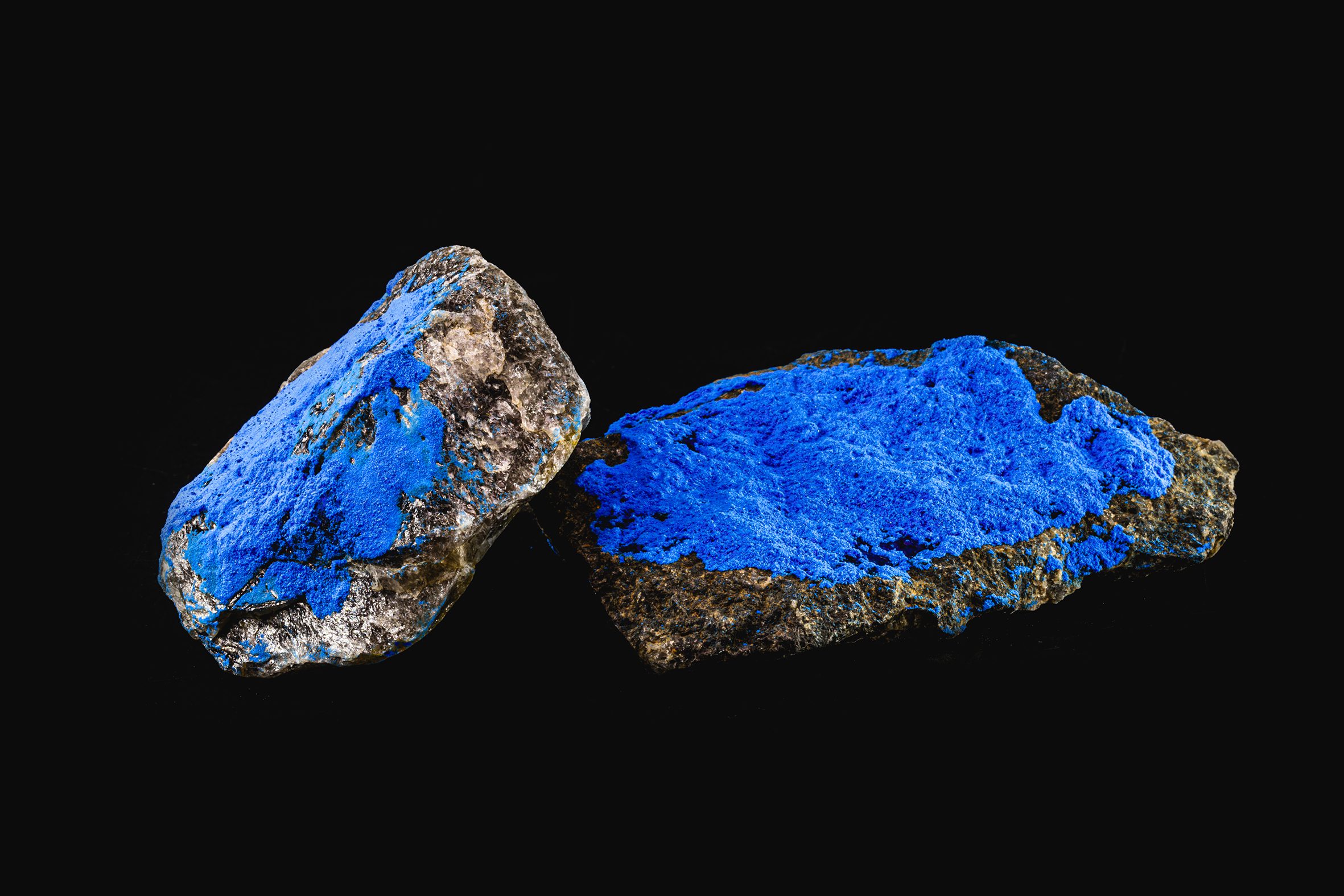

They found more than 700 nurdles, of all different colors, shapes and sizes. “They start to get kind of a white chalky appearance after they’ve been in the water for a long time,” he said, and nurdles also appear different depending on where they were made.

It was an alarming discovery that has implications beyond Shell, Clark said, although recently the team has been seeing more fresh, similar-looking nurdles that seem to have been in the water for a shorter period of time and could be linked to the Beaver County plant. They haven’t yet been able to procure a sample from Shell to match the nurdles definitively.

“That is a tiny area, smaller than half a sheet of plywood, and our preliminary analysis of what we’re looking at there didn’t point directly to a problem at Shell,” he said. “But it pointed to a plastics problem that we have throughout the whole region.”

To Clark, the “incredible” concentration of nurdles was evidence of the industry’s role in contributing to plastic pollution. “If we’re finding that amount of plastic spread through our environment that is the responsibility of manufacturers—these are plastic nurdles, they’re not from consumers—we have a real serious issue with the lack of regulation of plastics manufacturing,” he said.

I spoke with Clark and Heather Hulton VanTassel, the executive director of Three Rivers Waterkeeper, about their efforts to track pollution coming from the Shell plant and what its presence means for Beaver County and the region.

What are some of your concerns about the Shell plant’s effects on the environment and the river?

Heather Hulton VanTassel: It is built upon a heavily contaminated site. We have a lot of zinc, thallium and aluminum that’s on site, and we see a lot of stormwater issues with those heavy metals. They’re self-reporting a lot of heavy metal contamination through their stormwater drainage into the Ohio River basin there. Those legacy contaminants are a major concern for us because they’re just not being contained at the level we believe they should be. And while they aren’t contaminants that Shell produced themselves, it is something that they took ownership of and are now liable for.

Evan Clark: They took over a really old industrial site that initially had been a lead smelter and then a zinc smelter. The legacy contamination from similar sites around the country is pretty well known, and their remediation, that was putting four maybe six inches of soil on top of that industrial site, doesn’t do a lot to prevent stormwater leaching into the river.

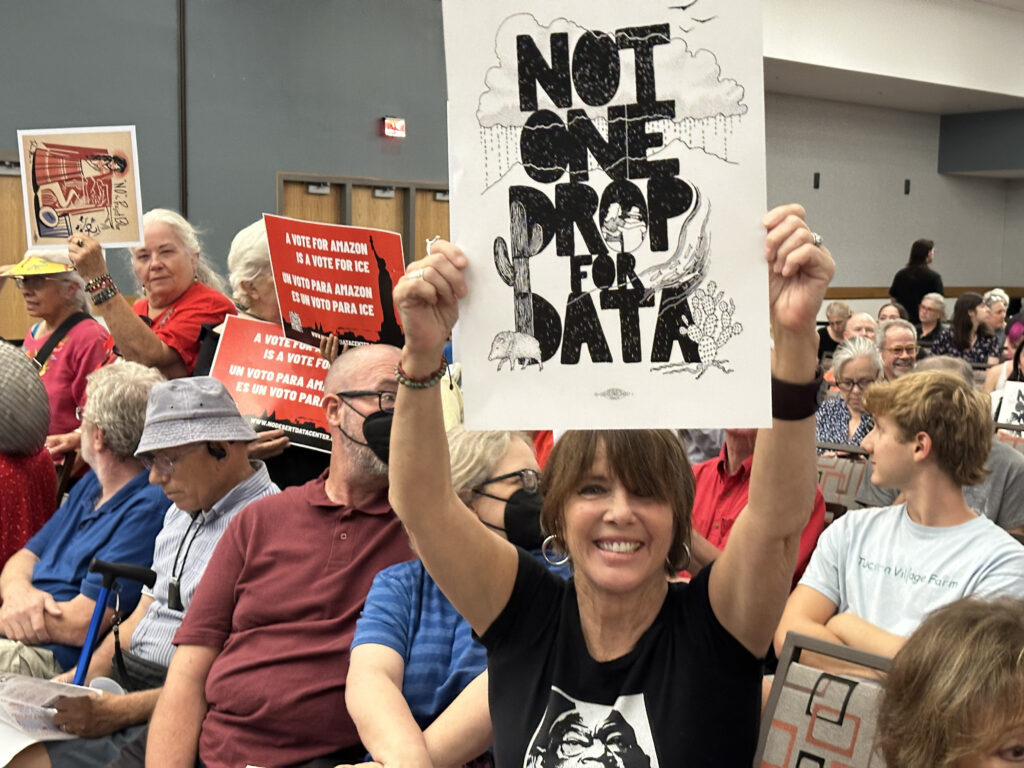

Evan Clark (left) and Heather Hulton VanTassel of the Three Rivers Waterkeeper, a water quality advocacy organization based in Pittsburgh. Credit: Three Rivers Waterkeeper

Hulton VanTassel: We’re concerned about their produced water, their wastewater, from their actual production process. Those [contaminants] are going to be things like benzene and other volatile organic compounds, things that we know are really carcinogenic and cause long term chronic health problems, but are also really hard to monitor. These things, even in small quantities, can be harmful to human health.

Recently our team has gone out to the Shell outfall and has been experiencing some odors that are typically associated with organic materials such as benzene that would be volatilizing from the water into the air. Shell has had more organics coming out of their main outfall than anticipated and are working towards reducing that through adding increased technology. However, they haven’t stopped production during this time period, and they continue to discharge more organics than anticipated.

We’re concerned about what a lot of people are concerned about, because it’s something very tangible, and that’s the loss of their plastic pellets that they’re producing. Those plastic pellets are commonly called nurdles once they enter the environment. They’re about the size of a Lego nubbin or a lentil. Once these things enter our waterways, they’re near impossible to clean up. A lot of critters that live in and around waterways mistake them for fish eggs and consume them, and it gets lodged in their systems. They can change densities of riverbeds because they’re typically much lighter than soil and can alter that type of substrate. They can further continue to break down into microplastics which then enter our drinking water systems as they are so small, and then enter our bodies.

More and more data is starting to show that plastics aren’t as inert as once thought when it comes to ingestion; they can absorb other chemical contaminants and offer a delivery system to our bodies of contamination. Some of the plastic itself has been shown to be harmful to the human body as well as aquatic life. We’re really concerned about the potential leakage of the plastic pellets into our environment, primarily because of how hard they are to clean. They don’t break down into natural components, they just break down into smaller and smaller pieces of plastics that can enter a body and cause harm.

Are you seeing an increased number of nurdles in the river?

Clark: When we look at the riverbanks around that area [near Shell], even though we haven’t necessarily been able to prove that some of the plastics that we’ve been finding have been coming from Shell, we find incredibly alarming amounts of manufactured plastic pellets, things that we typically call nurdles, all over the shorelines. They’re coming down from the headwaters of the Ohio River which is a good-sized area, but it’s not that massively large that it warrants the amount of manufactured plastic pellets we find. We’ve isolated a couple of square feet and scooped two inches of soil off of the top and found hundreds and hundreds of these pellets that are floated in on the river and have been deposited. It’s something that we’re especially concerned about at Shell, which has the capacity to be the largest plastic manufacturer in the country. That they’re adding more plastics to this already huge mix will be incredibly problematic, and it’s one of the big reasons we spend a lot of time watching them very closely.

What do you think the Shell plant’s presence will mean for the health of the river and the surrounding area in the long term?

Hulton VanTassel: It really depends on how Shell acts, and ultimately, we don’t know these answers. We do know that since before Shell was even operational, there were violations, and we know there continues to be violations. We do know that their discharges have impacts to both human and environmental health. What that looks like [long-term] is really uncertain, and some of these chemicals take years, if not decades, to show their true power.

It takes years if not decades to lead to chronic health issues and morbidity and in that time, people have been exposed to other things. It’s so challenging to prove without a doubt this causation of harm. We don’t operate in a laboratory setting when it comes to how people are exposed to environmental harm, which means there’s a lot of things that we can’t account for. Some people get sick, some people don’t.

Because there’s this inability for us to know exactly how each individual was impacted by exposure, that’s what industries use for saying it doesn’t cause harm. But we shouldn’t be waiting for everybody who is exposed to get cancer or have chronic lung issues or die. Rather, we know these chemicals cause harm, therefore we should protect our communities from exposure. We shouldn’t be waiting for 30 or 40 years from now to say, “Oh, this community got more sick than expected. Maybe we should have protected them.”

What do you think is most important for the public to know about this issue?

Hulton VanTassel: One of the things that really shocked me prior to becoming a Waterkeeper is that industries don’t necessarily get in trouble for the harm they’re doing. I would like the community to know that they can ask their regulatory agencies, in this case the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, to hold the polluters in their region accountable.

Bringing that cracker plant into our region has really opened up the doors to see how prevalent plastic production and harm is in Southwestern Pennsylvania. We have fracking and oil and gas extraction that comes with a lot of fracking waste that goes in landfills and leaches into our waterways. We have train derailments that happen in our communities carrying these products. We have nurdle spills that impact our aquatic life and will eventually break down into microplastics that harm humans. Then you have the whole process of turning those nurdles into something else, and that creates byproducts that get put into our waterways, and then those plastic materials find their way into homes and then eventually into our waterways, and those further break down.

The cracker planet created what feels like a mecca of plastics. We used to say that Pittsburgh is the Steel City of the United States. And now it really feels like, no, we’re the Plastic City of the United States. We have every component of plastic production from extraction to waste.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

How does pollution from other industrial sites and facilities in the region factor into what’s happening with Shell?

Hulton VanTassel: A lot of these places have already had past industrial pollution, and it might be that that community’s identity is tied to industry, so it’s easier for that community to accept another industry. The other aspect of this is permitting and zoning. This is a prime example, where Shell utilized an old facility and amended a permit, which was a much easier process that allowed for some grandfathering in of contamination levels that they most likely wouldn’t have been approved for otherwise. These are some of the ways that industries can utilize past harm to benefit themselves.

Because we have been an industrial city, people don’t look at our rivers the same way. They often say, “Well, they’re cleaner than they were. They’re dirty, and that’s just the way they’re always going to be,” and until we can flip that narrative where we demand that these industries are held accountable, and we don’t allow them to pollute our waterways, then yes, that’s how they’re always going to be.

But we can demand accountability. We can ask for better regulations on what’s being discharged into our waterways. And that’s the conversation we’re working to have, to change people’s idea that our waters are polluted, and there’s nothing we can do about it. Because there are things we can do about it. We just need to do it as a collective.