Every state in the country trails California in the number of electric vehicles on its roads and the available public chargers. But research has found those cars and chargers are concentrated in wealthier communities—an imbalance that has raised questions about the fairness of a key state climate program targeting transportation emissions.

California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) aims to lower emissions by incentivizing “alternative fuels” and encouraging certain technologies. Over the past decade, the complex fuel standard has been credited with reducing diesel and gasoline emissions by nearly 13 percent.

The LCFS has also generated controversy: it includes generous incentives for biogas and biofuels, which have surged in production and been criticized by environmental advocates as contributing to pollution. Researchers also have suggested that the program’s emissions reductions may be overstated.

Now California regulators are proposing an LCFS update slated for approval in the coming months. In addition to extending incentives for gas produced from dairy manure, biofuels and some carbon removal technologies, the proposal could inflate gasoline prices by tens of cents a gallon in the next decade—and by more than a dollar per gallon in the late 2030s.

We’re hiring!

Please take a look at the new openings in our newsroom.

See jobs

Environmental justice advocates say the LCFS already harms rural California communities by creating more air and water pollution from agriculture. Now they worry the updated program will impact communities where EVs are often financially out of reach.

Daniel Ress, a staff attorney at the Center on Race, Poverty and the Environment, a national nonprofit that provides legal and organizing support in low-income communities, said the gas increases amount to a “regressive tax.” “This is the height of injustice,” said Ress, during a September public hearing on the proposed LCFS changes.

Historically, the LCFS has had only a modest impact on California gas prices, according to Jeremy Martin, director of fuels policy at the nonprofit Union of Concerned Scientists. Fuel prices are influenced by numerous factors, including refinery availability, taxes, and even the season. “Fuel pricing is quite opaque,” he said.

But the state agency that leads California climate policy, the California Air Resources Board, assessed the economic impact of the proposed policy in September and found that Californians who buy gasoline and diesel for cars and trucks could see significantly higher prices after its implementation. Three months later, a staff report from the same agency hedged those findings and said the analysis was incomplete and the costs hard to predict. This month, in an emailed statement to Inside Climate News, a spokesperson for the air resources board said the latest academic research “indicates that there is no proven link between the LCFS and gasoline prices.”

In the analysis published in September, the board estimated gas price increases could average nearly 40 cents a gallon through 2030. Researchers from Stanford University submitted a written comment in February that suggested price increases could exceed $1.50 a gallon by the end of this decade, when considering both the LCFS and the state’s cap-and-trade program.

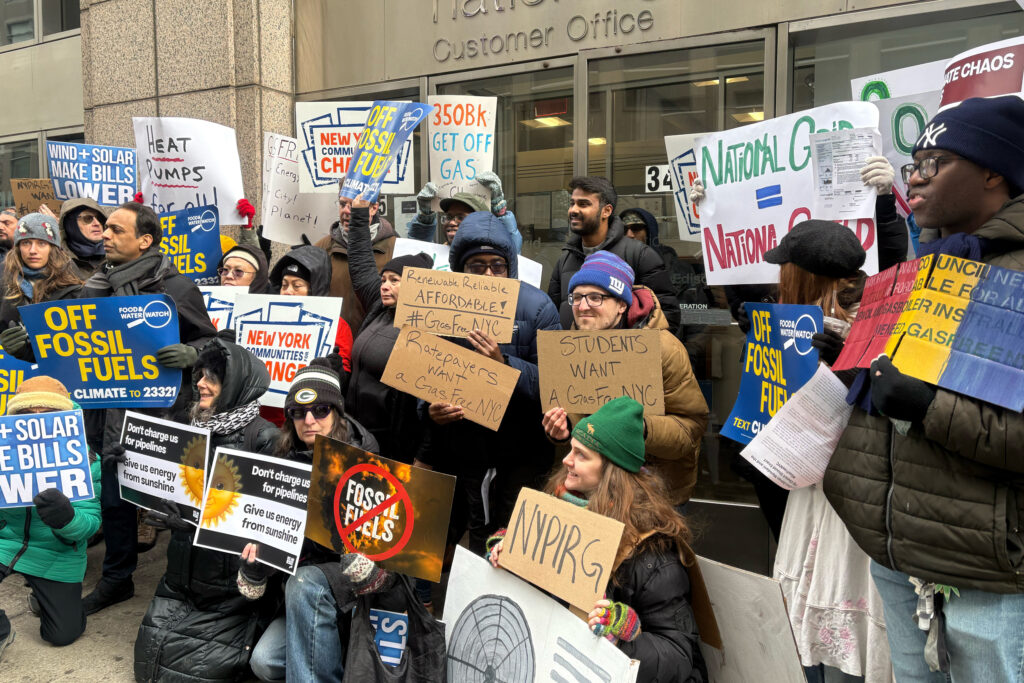

“It can be a complicated final number to land at, but I don’t think there’s any dispute that higher compliance costs in the LCFS will translate to higher prices at the pump,” said Tyler Lobdell, a staff attorney at Food & Water Watch, a nongovernmental group that focuses on corporate and government accountability.

California currently has the highest gasoline prices in the nation. In public comments submitted on the proposed changes, environmental justice groups and consumer advocates said any added burden from the LCFS would be untenable.

Many biogas and biofuel projects that receive LCFS credits are located in low-income communities or communities of color. In addition to coping with pollution from those facilities, Lobdell said, those residents would now face higher gas prices to support the program. “It’s unethical,” he said of the proposed changes.

“A shrinking number of gas consumers will be paying to supposedly address pollution from the dairy industry,” Lobdell added. “The Low Carbon Fuel Standard is undermining California’s ability to implement a truly just and effective transition in the transportation sector.”

EV purchases in California continue to climb, but there is an economic and racial divide in the sales numbers. By 2035, all new cars sold in California must be zero-emissions, but many people will still be driving older, gasoline-powered models.

“The used car market is where most Californians live, right? They don’t live in the new car market. And so those people are the ones who are going to be affected by this,” said Michael Wara, who directs the climate and energy policy program at Stanford University.

In a 2023 analysis of California vehicle registrations and EV rebates, researchers at Stanford and the University of Michigan found that residents in formerly red-lined neighborhoods owned fewer battery-powered cars and received fewer rebates. A similar trend emerged across low-income areas: people in those neighborhoods also owned fewer EVs and received fewer rebates. In zip codes where the majority of residents are Latino, in both high-income and low-income areas, the population had the lowest number of EV registrations and received the fewest rebates.

Similar income and race-related trends for public EV chargers were reflected in an analysis by Humboldt State University researchers in 2021.

“There have been these income-related disparities, there have been these race-related disparities, and they’ve been pretty persistent over time since electric vehicles really hit the market,” said Eleanor Hennessy, an author of the Stanford study and now a postdoctoral scholar at Arizona State University. “If we have these communities that really haven’t started the transition yet, they’re going to be hit a lot harder by increases in gas prices.”

California has created programs to alleviate the EV gap. Low-income Californians in certain regions can apply for funds to help pay for EVs, including used cars. Some LCFS benefits go to EV rebate and charging programs.

But some environmental justice groups say the incentives are insufficient, particularly when low-income Californians are rarely purchasing new cars. Lobdell of Food & Water Watch called the LCFS a “broken program.”

Some experts and environmental advocates who acknowledge reservations about the proposed changes are also wary about harshly criticizing the LCFS because they say it has provided notable climate benefits. Transportation accounts for the majority of California emissions.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

“This program has been very successful and plays an incredibly important role in the climate policy portfolio,” said Colin Murphy, co-director of the Low Carbon Fuel Policy Research Initiative at the University of California, Davis. “Over the long run, if we don’t do something about climate change, the economic costs are much, much worse than what would happen from gas price impacts due to the LCFS.”

Martin of the Union of Concerned Scientists said the program can be fixed. “The program has been a good program, moving us in the right direction, and it can be that again.”

In written public comments, Martin and other researchers including Wara at Stanford called for a limit on biofuels. California’s consumption of biofuels, which are often produced from crops like soybeans, has grown from 1 million barrels when the LCFS was implemented in 2011 to more than 28 million barrels in 2021. Researchers say skyrocketing demand could increase emissions by expanding carbon-intensive agriculture. Environmental justice groups and communities also want the air resources board to eliminate credits for gas produced from dairy manure; subsidies that Martin says are “counterproductive.” Some residents believe the incentives are pushing dairy herds to grow—and increase pollution—and some researchers say these incentives are a roundabout way to regulate the pollution from California’s large dairy industry.

The currently proposed changes keep incentives in place for both types of fuels. The air resources board was set to vote on those changes this month, but delayed the vote in order to address “the large volume of public comments” on the amendments. The agency plans to hold a public meeting in April.