ALBUQUERQUE, New Mexico—The Navajo Nation’s transition from producing fossil fuels to generating renewable energy is going through some growing pains.

Tribal and chapter government officials, energy companies, nonprofit organizations and others attended a three-day conference last week to discuss the tribe’s history with energy production, and the challenges of redefining that relationship, including how to best take advantage of financial incentives rolled out by the Biden administration for developing renewable energy sources.

“From my perspective, we have one shot, and this is it,” said Mike Halona, executive director of the tribe’s Division of Natural Resources. “The players are all in the room. How can we solidify, when we leave here, a good common goal to be able to make these projects happen?”

We’re hiring!

Please take a look at the new openings in our newsroom.

See jobs

When Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren took office in January 2023, he prioritized examining energy development, Halona explained.

“We’re all here to address the needs of the Navajo people—the ultimate goal. I think that’s what brings us all together,” Halona said.

Traditionally, the Diné governed themselves through clan relations. It was not until 1923 that the U.S. Department of the Interior formed a centralized Navajo government as companies began exploring and extracting natural resources from the tribe’s land.

The removal of coal, oil, gas, helium, sand and gravel continues, according to the tribe’s minerals department.

For almost 100 years, the tribe has been heavily dependent on fossil fuel extraction to provide revenue for its annual budget, which helps fund programs, departments and services.

Revenue from coal production started to decline in the early 2000s with the closure of the Black Mesa Mine in Arizona and the McKinley Mine in New Mexico, according to the minerals department.

Another drop happened in 2019 when the Kayenta Mine closed because of the shutdown of the Navajo Generating Station near Page, Arizona. The Navajo Mine near Farmington, New Mexico is the only coal mine still operating on the tribe’s land.

In 2020, oil production also decreased because of the COVID-19 pandemic but it has recovered as demand returned, said Rowena Cheromiah, minerals department director.

The U.S. Department of Energy Office of Indian Energy Policy and Programs helps fund and implement programs and projects that promote tribal energy development, strengthen tribes’ energy and economic infrastructure and help bring electricity to tribal lands and homes.

Wahleah Johns heads the office, a post she was appointed to by the Biden administration in 2021. She is Diné from the Black Mesa area in northeast Arizona. Her background, which includes advocating for renewable projects, helps her understand the challenges tribal governments face in energy development and creating projects that enhance tribal members’ lives.

“We hear everything from homes not having electricity, homes not having adequate power … to big ideas of tribes trying to build transmission, tribes trying to do clean energy projects to create economic development,” she said.

The federal government and the Navajo Nation signed a memorandum of understanding to ease the tribe’s access to federal funding available through at least four resources, including the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the Inflation Reduction Act. Any funding, if awarded, would help the tribe’s clean energy transition and efforts to revitalize their economy. The Hopi Tribe, also hit economically by coal mine closures, has a similar MOU with the federal government.

Solar development is happening over the Navajo’s 27,000 square miles of land. Independent operators have been installing standalone solar systems at homes that, for many tribal members, are providing the first electricity that has flowed inside their residences. However, the Interior Department reported last year that 21 percent of homes on the Navajo Nation still lack electricity.

The Navajo Tribal Utility Authority, a tribal enterprise, built two solar farms in 2017 and in 2019, both located north of Kayenta, Arizona. Their latest site, Red Mesa Tapaha Solar Project, started operating last year. NTUA continues to collaborate with communities to develop more solar production sites.

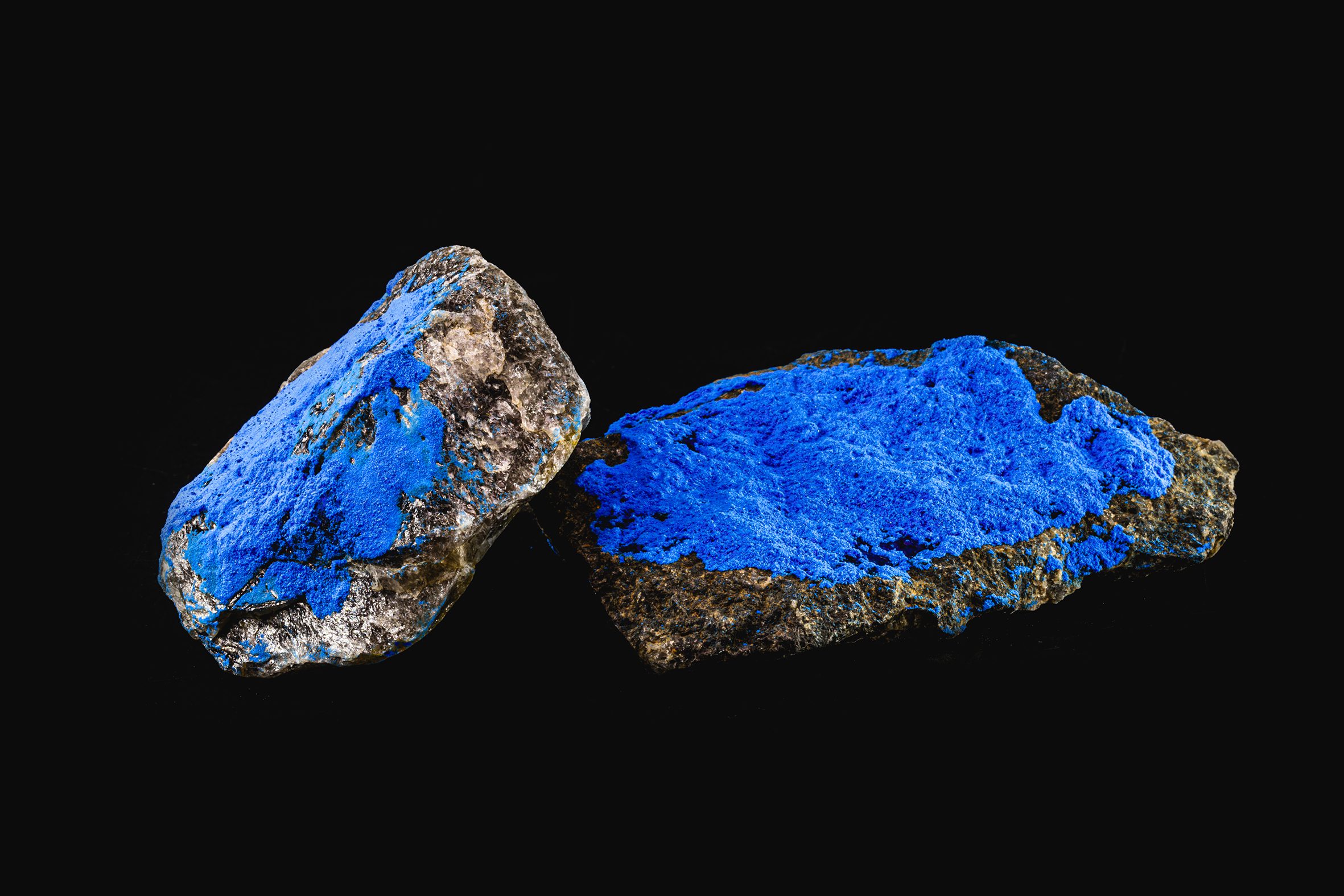

The Navajo Transitional Energy Company, another tribal enterprise, has the only helium production site on the Navajo Nation in an area known as the Tocito Dome Field in New Mexico. Helium can be used for electronics, semiconductors, MRI machines and welding.

In December 2022, the Navajo Nation Council supported a proposal by another tribal enterprise, Navajo Nation Oil & Gas Company, to build more helium production sites in New Mexico and Arizona. Before leaving office in January 2023, then tribal President Jonathan Nez vetoed the bill because it lacked consensus by communities that would be impacted by extraction activities.

Hydrogen could also be coming to Navajo land, although not for the tribe’s use. Tallgrass Energy, through its subsidiary GreenView, is proposing a pipeline that would cross the Navajo Nation to deliver hydrogen from New Mexico to Arizona. GreenView’s website does not have details about the project, which continues to receive mixed reactions from tribal members. Hydrogen can be used in fuel cells to generate electricity and to power vehicles, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

“One of my priorities is that the Navajo Nation have ownership or equity in projects developed on the nation,” Nygren said in a statement read to attendees.

This means outside businesses working with the tribe’s enterprises to decarbonize the tribe’s economy and provide jobs closer to home, he said. The tribal president did not attend the conference because he was meeting with congressional members for support of water rights settlements.

The Office of Indian Energy also supports funding for tribes to have an energy manager, who would oversee production opportunities.

The Navajo tribal council adopted its first energy policy in 1980, then revised and replaced it in 2013. This policy addresses exploration, development, sustainable management and use of the tribe’s energy resources.

It also called for establishing an energy office to function as a clearinghouse for energy-related projects and facilitator for energy development on the Navajo Nation.

But a decade has passed since the policy went into effect and the office still does not exist. Tribal council delegates have made attempts to set up the office without success. This lack of structure has caused confusion about who is responsible for project proposals and who companies approach with their project ideas, leading to calls for another reworking of the policy.

“A lot has happened since then,” said April Quinn, principal attorney with the tribe’s Office of Legislative Counsel, of the 2013 policy.

“I think there is sort of a consensus that what has happened since the adoption of this policy has basically rendered it very outdated and there’s a need for a new policy,” she added.

Cheyenne Antonio listened to the presentation in the large conference room and expressed disappointment in the policy because it does not address remediation.

To her, remediation should have been included because the tribe continues to fight for cleanup of abandoned uranium mines and orphaned oil and gas wells.

“It’s just like all this planning, but no accountability to the community,” Antonio said.

Antonio, the energy organizer with Diné C.A.R.E, comes from the eastern part of the Navajo Nation, where pumpjacks and tank trucks are familiar sights.

“I get that we want to be sovereign with our own energy, but at what costs?” she said.

Communities on Black Mesa understand the spectrum of coal mining—from job opportunities, environmental impact to redeveloping the area’s economy.

“A lot of people think we got a lot of benefit from the operation of the mine. We didn’t. We didn’t,” said Rose Yazzie with Black Mesa United.

The grassroots group dedicated to uplifting the region wants to reuse resources left behind by the mining operator.

Yazzie said the group wants the tribe to acquire a building left by Peabody Western Coal Company at the mining site so community members can use it. Peabody operated the Black Mesa and Kayenta surface coal mines from 1970 until 2019. The Black Mesa mine stopped operating in 2005. The mine controversially used water from the Navajo aquifer to deliver coal through a 273-mile-long slurry pipeline to the Mohave Generating Station in Laughlin, Nevada. The Kayenta Mine delivered coal by electric railroad to the Navajo Generating Station near Page, Arizona. That mine and power plant closed in 2019.

Nygren, the tribe’s president, reiterated in May his support to obtain the building, according to a news release from his office.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

Black Mesa United is not alone when it comes to transforming the region. Nonprofit organizations Tó Nizhóní Ání and Grand Canyon Trust are also working on viable opportunities.

Nicole Horseherder, executive director of Tó Nizhóní Ání, said they are working on a “just transition” for the communities, as well as advocating for community involvement in the decision-making process and ethical practices by outside companies that are attempting to develop energy projects on Black Mesa.

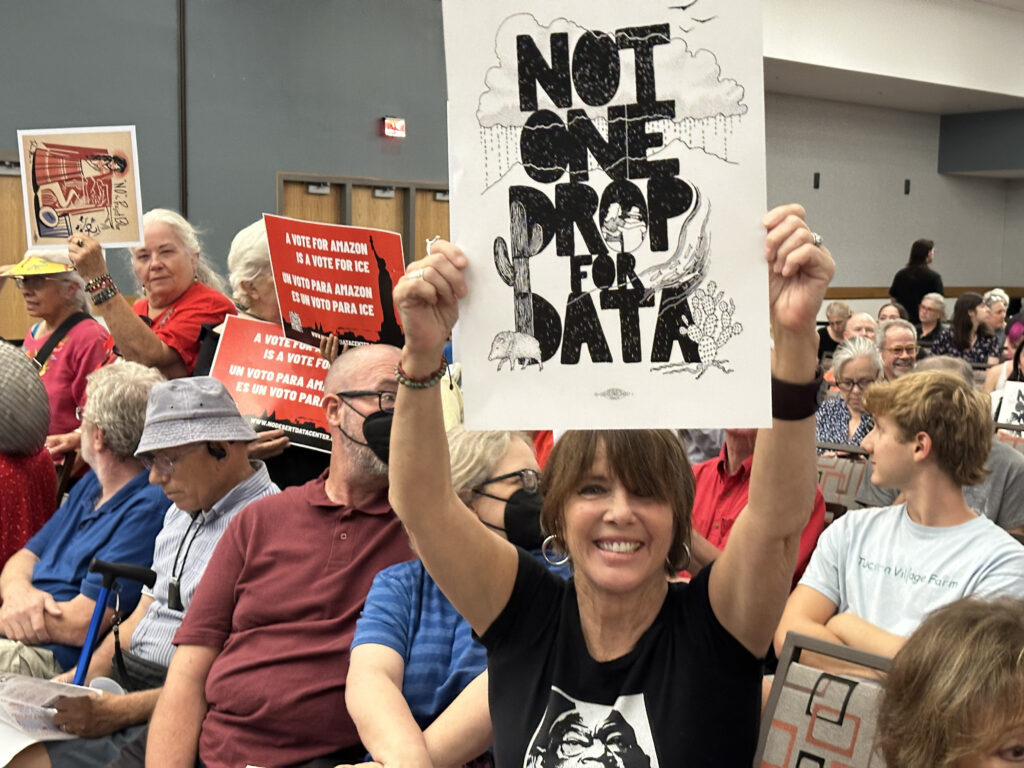

Gaining a tribe’s input and consensus on energy proposals took center stage in February when the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission denied preliminary permits for three pumped storage hydropower projects on Black Mesa. In their decision, the commission expressed concern about the lack of support from communities where the projects would be located. Additionally, the FERC implemented a new policy requiring companies to receive consent from tribes for projects.

“Gone are the days when companies come and offer just jobs and revenues for the nation,” Horseherder said. “There has to be a backup plan. There has to be a transition plan. There has to be a good reclamation plan.”