New requirements for construction projects to achieve a 10% net gain in biodiversity or habitats came into force on 12 February. The scheme is a milestone in that it moves biodiversity from an aspiration to a mandatory requirement for obtaining planning permission. But how well placed is it to succeed? And what tools are available to help?

Commentators seemed unanimous that the new requirements were a step in the right direction, if a little unambitious, with a government impact assessment acknowledging that 10% Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) may not go beyond “no net loss”. It remains to be seen how many councils will follow the example of a small selection of frontrunners who have set more ambitious requirements, notably Guildford and Worthing (20% BNG), and Tower Hamlets and Kingston-upon-Thames (30% BNG).

An FoI request sent to 317 local authorities in England appeared to show that only 26 (or 8%) have either committed to, or are considering, BNG requirements that exceed the mandatory 10%, as nature charity Wildlife and Countryside Link reported.

Richard Benwell, CEO of the group, said: “We really welcome the introduction of mandatory net gain. Done well, it could help turn around the decline of species and habitats, from dormice and red squirrels to meadows and woodlands, and give communities more natural spaces to enjoy. “But the law is too lenient. It will make no dent at all in the £5bn annual gap in funding for nature recovery. Added to concerns about Local Authorities’ capacity to enforce the rules, there’s real concern that net gain will only amount to a glorified offsetting scheme. While 10% may help prevent a decline, Government must support much higher ambitions to restore nature.

The charity published details of 18 local authorities who have emerging BNG policies above 10%, and said that these success storties “show that there’s real appetite among Local Authorities to go further for nature, but there’s a real risk that without support many areas lose out on this opportunity. The Government should publish clear guidance to support Local Authorities to go further for nature and raise the bar for biodiversity net gain.

There seemed no shortage of commentary on the practicalities of implementing BNG, and the shortfalls in this respect at present. Software firm AiDash said the scheme was “in desperate need of practical modern solutions to achieve those well-intentioned ambitions, with UK businesses facing the enormous and costly task of sourcing appropriate and

timely expertise and support.

Near the top of the list seemed to be “an alarming scarcity of qualified ecologists to carry out the volume of necessary work”, which AiDash estimated at approximately 150,000 BNG project applications expected to be submitted annually. The group’s calculation was that the UK will need 40% more ecologists – or 4,000 to 6,000 – to meet demand.

“Even then, the complex logistics of gathering specific data, especially in hard-to-access areas or large habitats, will leave BNG’s credibility at severe risk of being compromised by a wave of inadequate and imprecise data. A

fate well-documented in the recent history of the global carbon credits market. Moreover, the lack of human resource brings with it substantial implications in terms of missed deadlines and soaring costs.

Desktop progress

New technologies might help bridge the skills gap, suggested the group, whose own BNGAI software is being introduced for this purpose. BNGAI uses AI and satellite data to provide habitat mapping, detection of invasive plants, and data to help profile the health of trees and plant populations.

Another new tool appearing in the wake of the legislation’s announcement was from environmental consultancy Temple, which has joined forces with Esri to use the latter’s GIS (Geographic Information System) technology to develop innovative software solutions for clients. The UKHab and BNG Survey App was said to be the first application to help AEC (Architecture, Engineering and Construction) organisations make decisions on development plans and meet the new BNG requirements. As Temple’s CEO Mark Skelton put it, “new digital workflows mean users can now manage a project’s impact on the landscape and comply with the new law in a highly accurate and efficient way.”

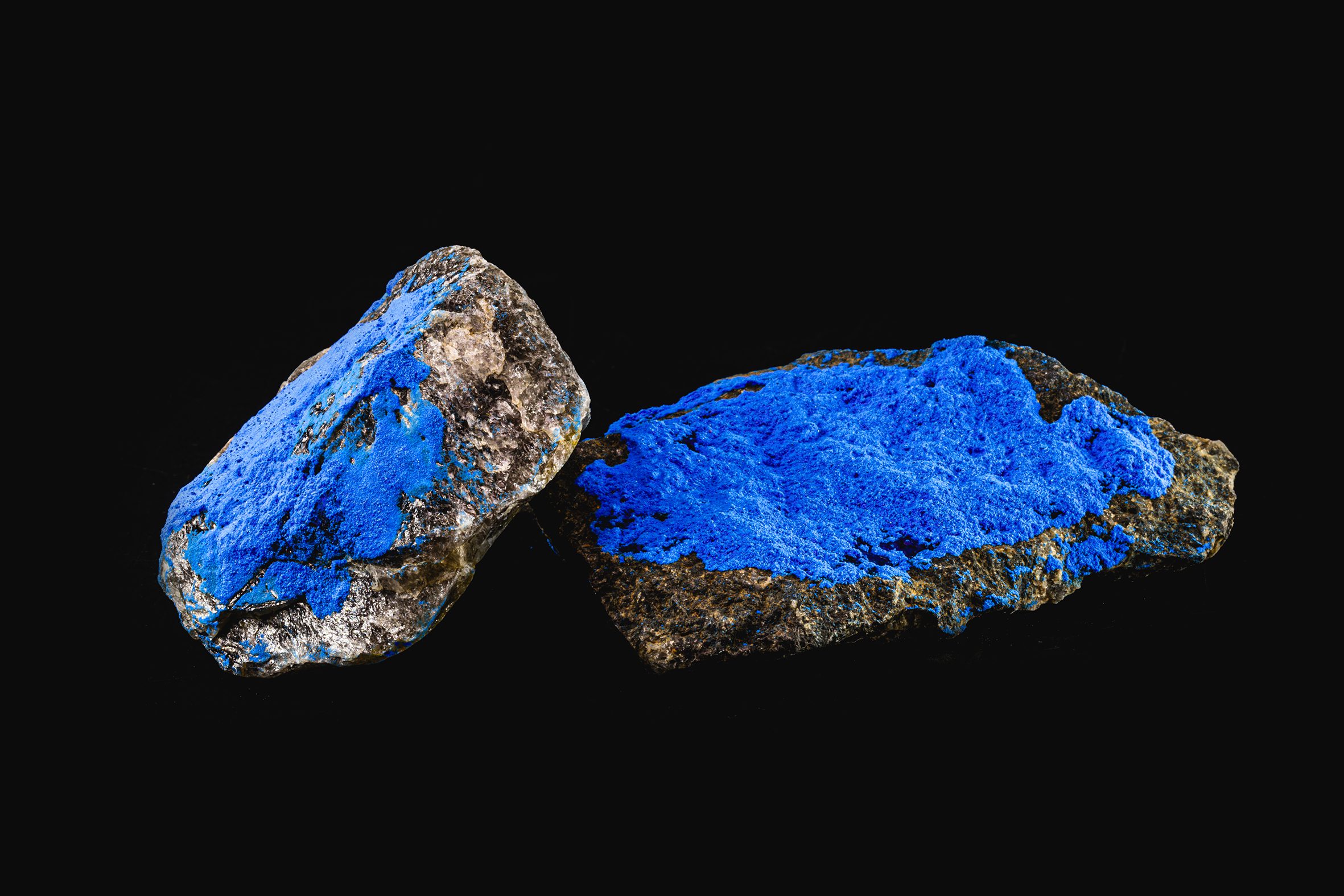

Holcim, a specialist in sustainable construction, said increasing BNG to 10% will require architects, urban designers and contractors to adjust how new buildings and developments are designed and constructed.

Holcim’s own research seemingly highlighted the mileage to be gained from measures such as introducing green spaces between buildings and using particular low-carbon construction products. For example, porous paving tiles, which allow rain to reach the ground and replenish groundwater. Green roof systems and bio-active concrete were also

mentioned as supportive of biodiversity improvements.

While it’s early days when it comes to working out the ‘how’ aspects of implementation, the appearance of a mandated requirement seems a landmark an a harbinger of change, in the way development is approached.

As Angus Walker, a partner at law firm BDB Pitmans reflected: “While there is likely to be a dip in the number of planning applications immediately following the rules coming into effect, as the regime becomes more familiar to

developers and more landowners realise the economic benefits it offers them, activity will pick up and buying BNG land will become another routine part of the planning process.”