DUBAI, United Arab Emirates—Under a blanket of petro-smog, more than half the 198 countries in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change called for a fossil fuel phaseout on the second day of COP28, marking a turning point after 27 years of climate negotiations.

Since the talks began at COP1 in Berlin in the spring of 1995, member nations have focused on temperature targets, voluntary emissions trading programs and other approaches that never addressed the root cause of the problem—the massive global increase of coal, oil and gas burning. At COP26 in Glasgow two years ago, the final conference documents for the first time included a timid reference to fossil fuels.

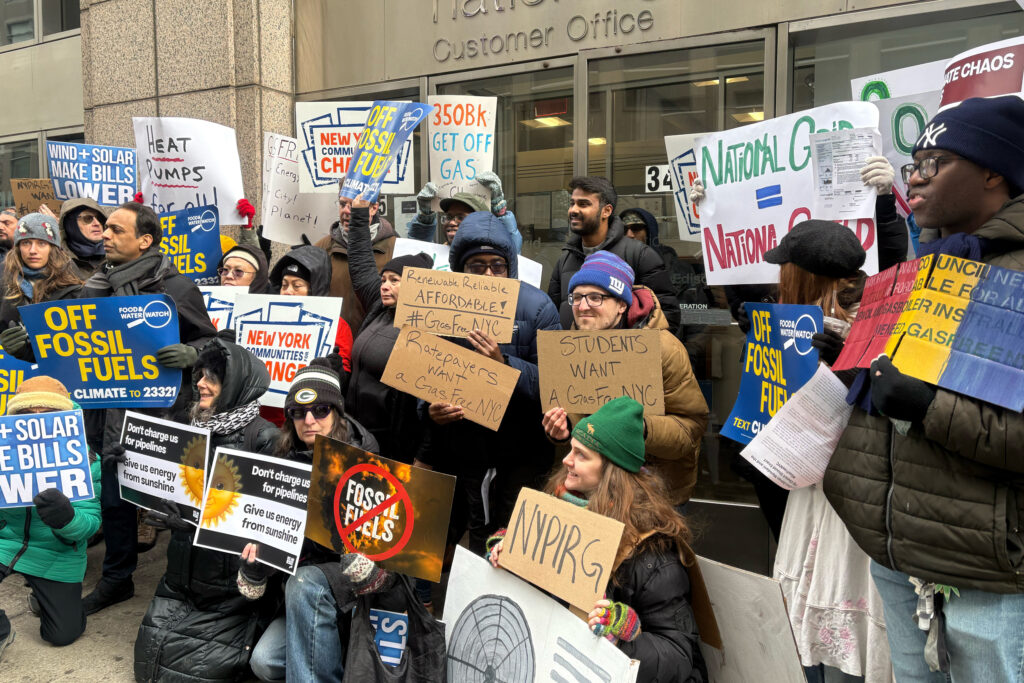

But Friday, 106 countries—27 member states of the European Union and the 79 members of the Organisation of African, Caribbean and Pacific States—finally took the issue head on, calling for a fossil fuel phaseout, an immediate end to all new oil and gas production and clear end dates for fossil fuel production.

“The shift towards a climate neutral economy, in line with the 1.5 degree Celsius goal, will require the global phase out of unabated fossil fuels and a peak in their consumption already in this decade,” those countries said in a joint statement.

Going into COP28, oil and gas-producing countries and rich developed nations like the U.S. tried to shift the focus toward language emphasizing a rapid deployment of renewable energy and a reduction in emissions from fossil fuels through technologies like carbon capture, not an phaseout of fossil fuels themselves.

But that’s not enough, Ambassador Pa’olelei Luteru of Samoa, current chair of the Association of Small Island States, said as COP28 began here in a petro-state, with the CEO of the United Arab Emirates oil company, Sultan al-Jaber, presiding over the Conference of the Parties.

“We call for a phase out of fossil fuels in line with science,” Luteru said. “Setting a target for tripling renewables would send a clear signal to markets but cannot be a substitute for a stronger commitment to fossil fuel phaseout.”

The call for a fossil fuel phase out from developing countries and small island states was backed up in a Dec. 1 joint statement by COP28 President al-Jaber and International Energy Agency director Fatih Birol, who said that, together with ramping up renewables, “fossil fuel demand and supply must phase-down this decade to keep 1.5 degrees Celsius within reach.”

Early U.S. Opposition to Climate Action Set The Stage For Decades of Delay

It’s not that climate negotiators who have gathered each year since 1995 didn’t understand that burning fossil fuels was the root cause of global warming. But they chose to omit it from the discussions by setting up the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change as a consensus-based process without power to establish mandatory, enforceable targets for reducing carbon emissions, largely due to pressure from the United States.

The UNFCCC is the foundational treaty that has served as the basis for international climate talks since it was signed by 155 countries in 1992. But President George H.W. Bush said then that the United States wouldn’t join the global effort if the treaty included specific targets and timetables for emissions reductions by rich countries.

“That’s the reason we’re still faffing around,” said Marc Hudson, a climate activist in the United Kingdom who has studied the history of COP talks. “The only reason we’re still having to have these bloody conferences was that in 1992, targets and timetables for emissions reductions by rich countries got taken out of the text.”

Even if those targets had been very modest initially, he said, they would probably have driven a lot of investment in energy efficiency and renewable energy. And it also would have meant that countries like China and South Korea, which weren’t in the “rich countries club” at the time, would have later been obliged to set their own targets for reducing emissions.

“The only reason they’ve been able to avoid doing that for this long is because the West has been entirely hypocritical and hasn’t done its own emissions reductions,” he said. “So for me, the battle was lost in 1992.”

The U.S. stance at the time was heavily influenced by an international lobbying group called the Global Climate Coalition, representing industrial interests and especially fossil fuel companies. The first chairman of the group’s board of directors was Thomas Lambrix, director of government relations for Phillips Petroleum, and other founding members included the National Coal Association, United States Chamber of Commerce, American Forest & Paper Association, and Edison Electric Institute.

Fossil Fuel Companies and Petrostates Shaped Climate Talks From The Beginning

The Global Climate Coalition disbanded in 2001, claiming victory after President George W. Bush withdrew the U.S. from the Kyoto Protocol, which killed the global goal of establishing mandatory emissions cuts. The legacy of that move has lingered to this day, shaping the foundational agreement for all subsequent climate negotiations.

That persistent influence is one of the main reasons the UNFCCC has failed to deliver, said Rachel Rose Jackson, who focuses on climate as director of research and international policy with Boston-based Corporate Accountability, a nonprofit group that tracks the environmentally harmful activities of transnational corporations.

“From day one fossil fuel interests, or those representing fossil fuel interests, have had a heavy hand in shaping the DNA of the UNFCCC,” she said. “Because when you set out to solve a global problem, and you give one of the VIP seats at the table to the very actors who are causing the problem, common sense tells you you’re not going to solve the problem.”

She said this is a deep, insidious problem that can only be solved by resetting the entire UNFCCC system so that it serves people and the planet, and not polluting interests.

“If there’s going to be any chance at this COP or any future COP delivering the action we so urgently need, we have to make sure that the fossil fuel industry’s influence over the outcomes is eliminated,” she said.

“It doesn’t have to be this way,” she said. “And that is what I think people forget. We get so used to COPS failing, and the UNFCCC not delivering, that we just get stuck in a cycle of assumption. We forget that there is no actual reason it has to be that way. Nothing in the procedures or protocol requires it to be this way. It really just is this handful of bad apples who are allowed to overrule the entire process.”

Time For a Change?

The time for change could be now, at COP28, after a year of devastating climate extremes that may be changing the way people perceive the role of fossil fuel interests in the global climate conversation, said Jennifer Layke, global director of the energy program with the World Resources Institute, a nonprofit international environmental think tank.

“We are in a moment of panic as a global community that cares very deeply about maintaining our ecological systems that sustain human life,” she said. “And I don’t think we can underestimate how real this is becoming for many people who are seeing the weather disruptions and impacts, and seeing the projections of where we’re headed.”

Growing anxiety over the role of the fossil fuel industry in the climate talks is partly based on the fact that time is running out.

“We are now well within the decade in which we need dramatic reductions in emissions,” she said. “And the question is if our institutions, our governments, as well as private sector actors and financial institutions, can meet the transition timeline. So it’s not surprising that we would be saying to the oil and gas community, or to the coal community, or to the transportation sector, or to the building sector, are you on track?”

Layke said she started working in the international environmental policy field as the Montreal Protocol to reduce ozone-depleting chemicals was being implemented, a process that can be an informative analogy for current efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

She said the success of the Montreal Protocol is one reason people have persistently pursued an international solution for the climate crisis. But the push to reduce greenhouse gases is much harder, she added.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

“This is not just a set of chemicals,” she said. “This is a transformation of every aspect of how we live, how we work, how we build our homes, how we travel. This is huge. It’s a path that is going to have bumps. And it’s going to be kind of messy.”

She said it’s easy to talk about an orderly transition, but not so easy to make it happen in the real world.

“I think we have to recognize that human systems don’t change in orderly fashion,” she said. “We have disruptions. And the question is, are we prepared with the institutions that will help us manage those disruptions?”

With a majority of the world’s nations now backing a fossil fuel phaseout with meaningful deadlines, some climate policy experts said the 27-year stalemate could finally be ending, but another nine days of talks remain before the conference’s final documents are written here in Dubai.