ALBANY—Citizens who breathe air polluted by New York’s largest landfill have no legal right under the state’s Green Amendment to block that facility’s application for a permit to expand, lawyers for the state Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) argue.

In a response filed Friday to a lawsuit against the DEC and the landfill, Seneca Meadows Inc., the agency asserted that it alone has discretion on when to issue, enforce, modify or revoke landfill permits.

“The Green Amendment does not alter DEC’s enforcement discretion … and so the plaintiffs cannot compel DEC to enforce against Seneca Meadows,” state Attorney General Letitia James argued in a May 31 filing for the agency.

We’re hiring!

Please take a look at the new openings in our newsroom.

See jobs

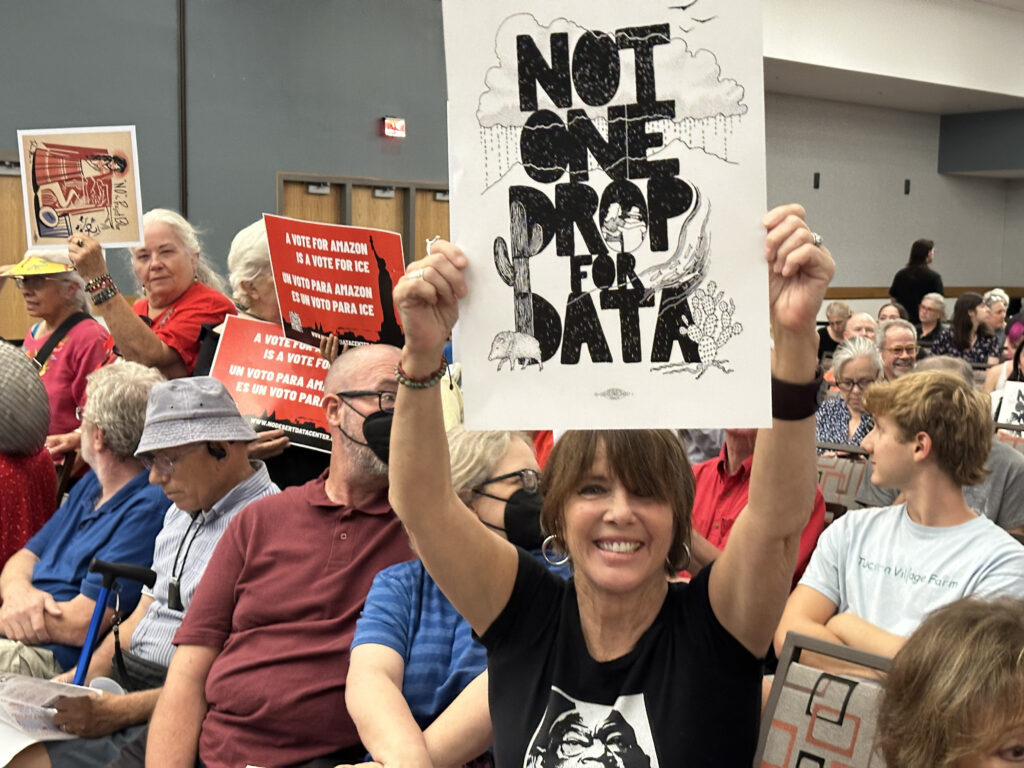

The lawsuit, filed in March by Seneca Lake Guardian and others, asks the state Supreme Court in Albany to issue an injunction to block Seneca Meadows’ application for a permit to expand.

It alleges that the DEC has failed to prevent the offensive stench from landfill emissions that may be harming the health of its neighbors in Seneca Falls and Waterloo. Plaintiffs noted that the state Department of Health determined that Seneca Meadows, which straddles two towns, was located within a “lung cancer cluster” from 2011 to 2015.

Without the new permit it seeks, SMI would soon run out of space to store garbage and be forced to close late next year. With it, the landfill could operate at current rates through 2040.

The Green Amendment, which took effect in January 2022, provides all New Yorkers a constitutional right to “clean air, clean water and a healthful environment.” But state courts are still in the early stages of defining the scope of the tersely-worded new right, which state voters approved by a 2-1 margin.

The Seneca Meadows case is just one of several where judges will weigh DEC arguments before settling on how the Green Amendment should be applied.

Neighbors of the state’s second largest landfill have also sued over foul odors that they say violate their Green Amendment rights. High Acres, which is owned by Waste Management Inc., is located in Perinton, about 15 miles southeast of Rochester.

In that case, Monroe County Supreme Court Judge John Ark held that the DEC has no special shield from Green Amendment claims, writing: “Complying with the Constitution is not optional for a state agency.”

In a December 2022 order, the judge ruled that the court “is fully entitled to compel” the state agency to comply with the constitution—through an order to close the landfill or take other steps to control landfill odors.

Ark also ruled that Green Amendment claims are not enforceable against private companies—only against the state. So he dismissed as defendants both High Acres and the City of New York, which provides more than 90 percent of the landfill’s garbage.

Ark’s order triggered an appeal by the DEC—and by High Acres, the dismissed defendant—to the Fourth Department of the Appellate Division of state court in Rochester.

Attorney General James submitted the DEC’s appeal brief in December 2023, writing: “The establishment of a constitutional right … does not impose a concomitant duty on the state to take action against third parties to enforce that right in the absence of language imposing that duty.”

In oral arguments before a Fourth Department panel May 20, Assistant Attorney General Brian Lusignan said High Acres plaintiffs were trying to circumvent existing state laws and rules governing solid waste facilities.

“There’s no evidence the Legislature (when it enacted the Green Amendment) wanted to allow private parties to bypass all that regulatory infrastructure and go directly to courts to litigate on a case-by-case basis whether a particular landfill should be shut down,” Lusignan said.

Attorney Alan Knauf countered for the plaintiffs, arguing that the state’s voters intended to “go beyond” existing law.

“They thought (the Green Amendment) meant that the state was going to be forced to do something more than what was on the books,” Knauf said.

Judge Ark had concluded that “defendants (the DEC) have not properly remedied the on-going problem …. The landfill is still causing odors and fugitive emissions which plague the community, therefore more needs to be done to protect (plaintiffs’) constitutional rights to clean air and a healthful environment.”

Knauf noted that both of High Acres’ key permits had lapsed and then been administratively renewed by the DEC with little or no public input even as the landfill failed to comply with state and local odor limits.

“So we’re going to wait for years on end while we’re bombarded by pollution?” Knauf asked the panel.

But Lusignan claimed the agency had taken numerous enforcement actions to try to reduce odors from the landfill. “This is not a case of abdication (by the DEC),” he said. “It is a case of diligent enforcement that the plaintiffs think is not enough.”

When asked by appellate judge Scott J. DelConte, Lusignan agreed that the Green Amendment did bind the DEC in certain respects.

DelConte wondered whether it would be correct to say: “The state now has a non-discretionary duty to make sure executive and legislative actions do not infringe on the rights of New Yorkers.”

“I would agree,” Lusignan responded. But that duty does not include surrendering its discretion on enforcement, he added.

Meanwhile, DelConte asked Brian Ginsberg, an attorney for Waste Management, why he was at the hearing, given that Ark had dismissed the parent company of High Acres as a defendant.

“Didn’t you win?” DelConte asked, drawing chuckles from the other judges.

“We were certainly excised from the caption,” Ginsberg said. “But we’re not out of the case in a meaningful way because we don’t want an order from the court saying the state (must order High Acres to close).”

Ginsberg urged the appeals court to dismiss the case on the grounds that the Green Amendment is not “self-executing,” that is, it cannot be enforced without enabling legislation that defines “clean air” and specifies the duties of state agencies. Ark had dismissed that argument, finding that the Green Amendment is self-executing.

In response to the Seneca Meadows lawsuit, Michael Murphy also argued on behalf of the landfill that the Green Amendment is not self-executing. He asked the Albany court to dismiss the case against SMI on those grounds.

The Green Amendment “creates no new avenues for interfering with the operations of a privately run landfill, DEC’s enforcement discretion or an ongoing permit review process,” Murphy wrote in a May 31 brief.

“Because the permit review process is incomplete, plaintiffs cannot allege the irreparable injury needed for injunctive relief,” he added. “Depending on its findings, DEC could issue a permit with conditions to address plaintiff’s concerns.”

The DEC agreed in its brief that the request for an injunction to halt the Seneca Meadows permit process is not ripe for judicial review.

More broadly, Attorney General James and Assistant AG Lucas C. McNamara argued that the state Legislature chose to give the DEC discretion over landfill permits and regulations. They noted that the agency oversees more than 10,000 air, water, solid waste and mining permits and “prioritizes enforcement” based on shifting public-safety and public-welfare needs.

“If plaintiffs can compel DEC enforcement here, then plaintiffs and courts, rather than DEC, will set DEC’s enforcement priorities,” said the brief, which was signed by McNamara. “The Legislature specifically sought to move beyond such ad hoc attempts to solve New York’s solid waste disposal challenges when it gave DEC regulatory authority.”

Both McNamara in the Seneca Meadows case and Lusignan in the High Acres case acknowledged that the Green Amendment places a duty on government actors not to infringe on protected environmental rights. McNamara added that while the provision protects citizens against “government intrusion … it does not place affirmative obligations on the government.”

Maya van Rossum, founder of Green Amendments for the Generations, a movement to enact environmental provisions in state laws across the county, disagrees.

“What is most striking to me is that the attorney general and the DEC are seeing the Green Amendment as a threat to their authority, rather than empowering it,” van Rossum said June 1.

She went on to say:

“No polluting entity has a right to desecrate the environment. It is not an entitlement they own. The ability to pollute and damage the environment is a ‘privilege’ granted by the state through permitting.

“When that permit as written, interpreted, applied, enforced or not enforced by state government results in a constitutional infringement, it is an infringement that can and must be addressed by the judicial branch of government, which is the branch charged with ensuring proper interpretation and application of our state and federal constitutions.”

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

Ark, who retired shortly after issuing his landmark 2022 order, took the first crack at shaping the application of New York’s Green Amendment in the High Acres case.

The Fourth Department will weigh in on the validity of his positions in its appeal ruling, which will almost certainly be appealed to the state’s highest court, the New York Court of Appeals.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court in Albany will decide whether to grant plaintiffs an injunction to block Seneca Meadows’ application for a permit to expand. The DEC has requested oral arguments in that case. The losing side is likely to appeal that outcome as well.