Wired for Profit: Third in a series about Alabama Power’s influence over electric rates, renewable energy, pollution and politics in the Yellowhammer State.

BUCKS, Ala.—South Alabama is where it all washes out.

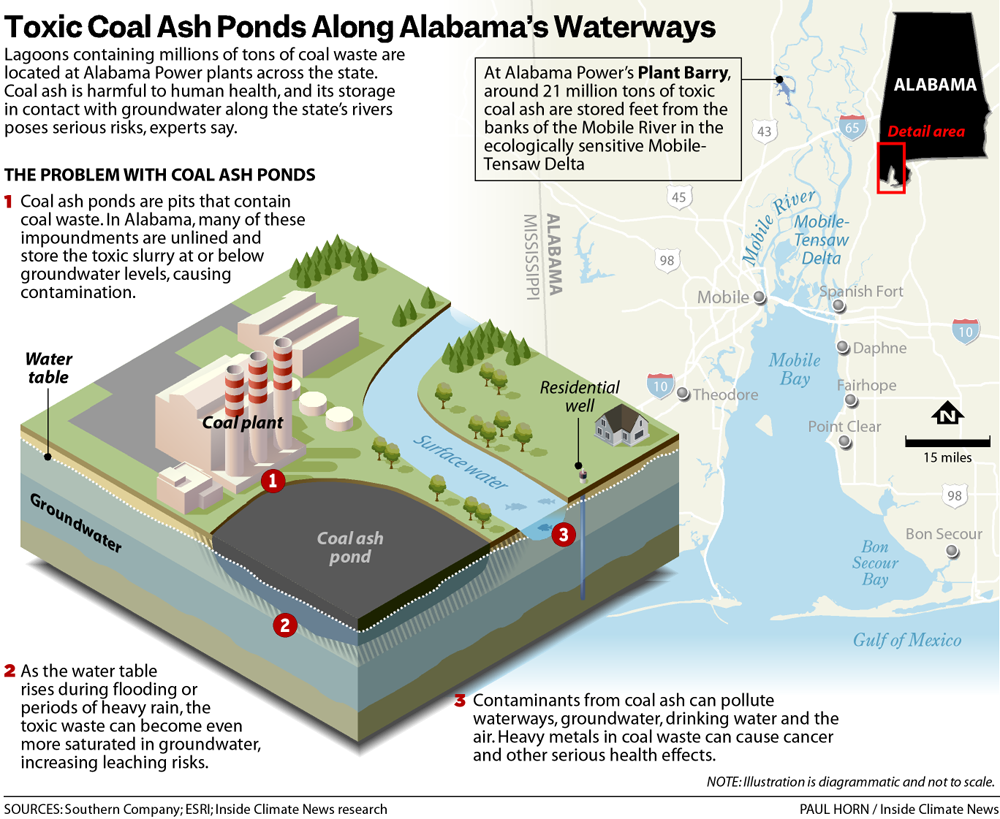

Here, in the nation’s second-largest delta, the waters of the Deep South wind through the pines and cypresses of the Yellowhammer State, snaking their way into Mobile Bay and on to the Gulf. Among the most biodiverse regions in the country, the Mobile-Tensaw Delta drains 44,000 square miles of Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi. It’s where the rivers—the Mobile, Tensaw, Blakely, Apalachee, Middle and Spanish Rivers—meet in land dubbed the “American Amazon” by E.O. Wilson, a renowned naturalist born in the state.

The Delta’s history is America’s. At its heart are the island mounds of Bottle Creek, the “principal political and religious center” for the Indigenous Pensacola culture for 300 years before European contact.

About a dozen miles south, beneath the surface of the Mobile River’s muddy waters, lies the wreckage of the Clotilda, widely regarded as the last slave ship to enter the United States. And farther south, still, the Mobile River empties into Mobile Bay, itself a veritable biodiversity hotspot and the cornerstone of a vibrant coastal culture and ecosystem.

But all of that, many residents, experts and environmentalists say, is at risk, because of Alabama Power’s coal ash waste, a toxic leftover from decades of burning coal for electricity.

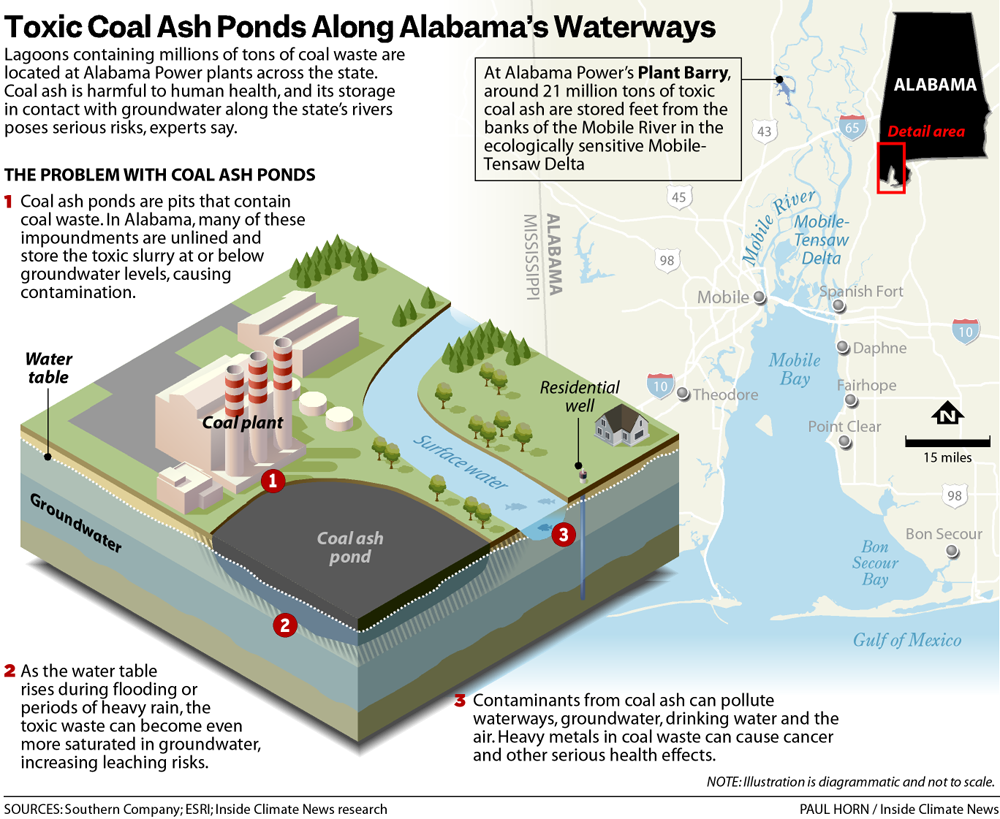

One 600-acre pit of the toxic coal ash lies along the banks of the Mobile River in the Upper Delta, about 25 miles north of Mobile Bay. There, smokestacks from the James M. Barry Electric Generating Plant rise like a sore thumb from a horizon of green, towering over an unlined pond filled with more than 21 million tons of the toxic residue. Holding back the toxic waste from the Mobile River? Earthen dikes.

Alyson Tucker, media relations manager for Alabama Power, one of the nation’s most profitable electric utilities and one of the state’s most powerful companies, said in an email that the company “remains committed to operating in full compliance with environmental regulations. Our plans for closure and groundwater protection fully comply with current state and federal law, are approved by [the Alabama Department of Environmental Management] and are certified by professional engineers.”

“Due to ongoing litigation related to Plant Barry coal ash, we are unable to comment further at this time,” Tucker said.

Leaving coal waste in place under engineered caps, company representatives have long argued, is safe and protective of groundwater—claims that state regulators have accepted but both environmental groups and federal regulators dispute.

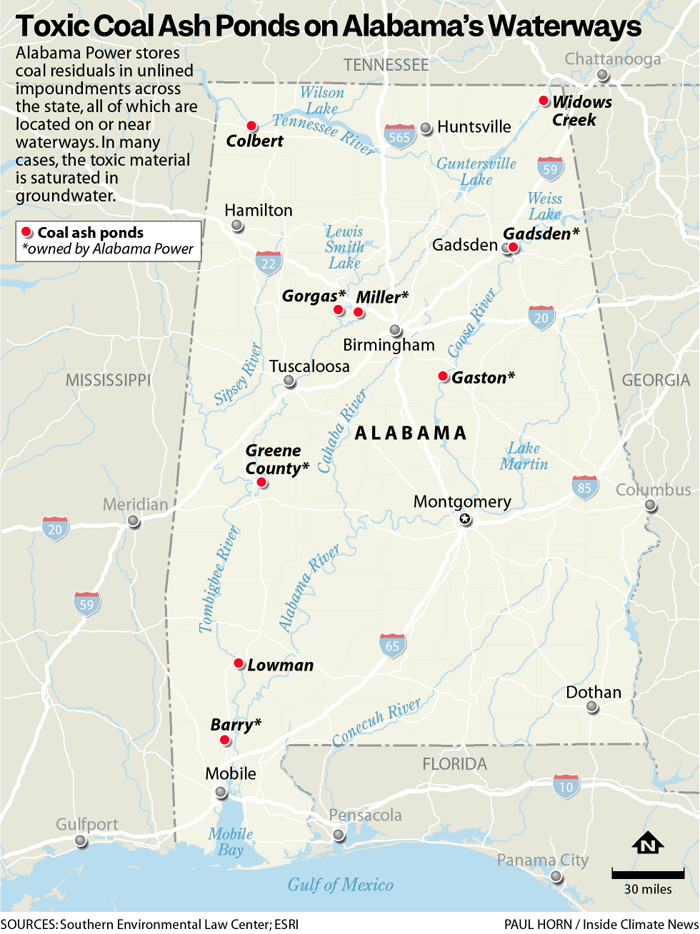

Alabama’s American Amazon isn’t the only area placed at risk by Alabama Power’s ghosts of energy past. An Inside Climate News review of the utility’s legally mandated emergency action plans shows that hundreds of square miles of land and waterways would be at risk of inundation in the event of a breach of the barriers holding back toxic waste at its six coal ash pond sites across the state. In total, more than 117 million tons of coal sludge are at issue, stored along Alabama’s waterways.

What to do with all that polluted material has become a controversial question, with federal and state officials at odds over the issue. In 2015, the federal government finalized a rule tightening restriction around how coal waste could be stored. EPA left implementation of the new standards to states, but in May 2024, the agency denied the state of Alabama’s plan to allow Alabama Power and other utilities to continue storing toxic coal ash in unlined pits at sites across the state. Federal officials said the plan would not adequately protect the state’s groundwater from contamination by coal ash residuals following “cap-in-place” closure.

“Under federal regulations, coal ash units cannot be closed in a way that allows coal ash to continue to spread contamination in groundwater after closure. In contrast, Alabama’s permit program does not require that groundwater contamination be adequately addressed during the closure of these coal ash units,” the decision said.

“The delta is an elegant labyrinth, full of bayous and sloughs and backwaters. If it is flooded with ash, it would be polluting forever.”

— Cade Kistler, Mobile Baykeeper

More than a year after the EPA denied Alabama’s coal ash plan, with the Trump administration now running the federal environmental agency, it’s unclear what comes next for the toxic ponds and the government’s now decade-old effort to safely close them.

But one thing is certain, according to Cade Kistler, who leads Mobile Baykeeper, an environmental nonprofit currently in litigation with Alabama Power over the coal ash lagoon at Plant Barry. Until the toxic leftovers of the company’s fossil fuel commitments are moved out of groundwater and away from waterways, the delta and Mobile Bay are an Eden on the edge of disaster.

“The delta is an elegant labyrinth, full of bayous and sloughs and backwaters. If it is flooded with ash, it would be polluting forever,” Kistler said. “There would be no way to effectively clean it up.”

The Costs of Kingston

The failure of a dirt dike at a coal ash pond isn’t theoretical. In 2008, a coal ash impoundment in Kingston, Tennessee, breached, spilling more than a billion gallons of toxic sludge across 300 acres of land and into the Emory River channel. The result was one of the largest environmental disasters in U.S. history. The spill cost the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), which owned the coal impoundment, over $1 billion to clean up. Ten years after the spill, dozens of the roughly 900 workers employed during the cleanup were already dead. More than 250 were chronically ill. According to the EPA, coal ash contains heavy metal contaminants like mercury, cadmium and arsenic known to cause cancer and other serious effects on the nervous system, heart, kidneys and development.

Both Alabama Power’s own groundwater monitoring reports and measurements taken by researchers from the Mobile River adjacent to Plant Barry confirm heavy metal contamination at the site.

“We identified a significant contribution of toxic metals linked to coal ash near Sister’s Creek, the man-made cooling discharge channel of Plant Barry, particularly during the dry season,” one 2025 study by scientists at the University of Alabama and Texas A&M Universities concluded. The peer-reviewed paper also pointed to the impacts of climate change as another reason to be wary of Alabama Power’s storage of coal ash on waterways.

“There is a plausible concern for acute and chronic toxic metals environmental pollution from the Alabama ash pond, considering rising seawater levels and more frequent severe storm surges in the region since its initial construction,” the study said.

The volume of coal ash material stored at Plant Barry alone is more than four times that of the sludge that spilled in Kingston in 2008, according to company figures. That fact alone should worry anyone concerned about Alabama’s environment, said Diane Thomas, one of three self-proclaimed “coal ash grannies” featured in a new documentary about Plant Barry’s coal lagoons, Sallie’s Ashes.

Thomas spent three decades living on the eastern shore of Mobile Bay.

“I have kayaked and sailed,” she said. “I swam. I crabbed. I fished. My love for the bay and what you can do on the bay runs deep.”

It was an easy “yes,” then, when her decades-long friend Sallie Smith asked Thomas and another friend, Savan Wilson, to help her fight against Alabama Power’s plans to leave coal ash beside the Mobile River. Smith had been diagnosed with terminal cancer and felt she needed to spend her remaining time advocating to protect the bay she’d grown to adore. The trio founded the Coal Ash Action Group, a grassroots organization committed to educating Alabamians about an issue unknown to many.

Thomas, a retired clinical psychologist, said it’s easy to fight for something so dear to so many. For decades, the delta and the bay have been an integral part of her family’s lives.

She smiled as she recalled her first jubilee, a naturally occurring event where low oxygen levels in Mobile Bay cause marine life to flee toward shore.

“There is nothing like catching your own crabs,” Thomas said. “Have you ever cleaned 200 crabs? Your thumbs are just raw.”

After her husband was diagnosed with stage four lung cancer, no longer able to work, he began to fish almost daily. With aggressive treatment, he survived the disease.

“We ate fresh fish for about eight years—four times a week,” Thomas said.

That type of close connection with the water is something Thomas feels shouldn’t be put at risk unnecessarily by an electric utility.

“A Knife to Your Throat”

Alabama Power’s legally-mandated emergency action plan for Plant Barry shows that if earthen dikes separating the coal ash from the Mobile River were to breach, around 25 square miles of the Mobile-Tensaw Delta would be inundated with coal slurry, covering dozens of miles of the Mobile, Middle and Tensaw Rivers, just upstream of Mobile Bay. From there, the toxic sludge would diffuse throughout the region, with the state’s rivers acting as a heart, pumping the liquid farther and farther from Plant Barry.

“But instead of lifeblood, it’s pumping coal waste that would kill the environment,” Thomas said.

David Bronner, the prominent CEO of the Retirement Systems of Alabama, recently called Plant Barry’s coal ash pond “a huge environmental bomb” in a newsletter sent to state retirees.

“We need your cooperation again for South Alabama,” Bronner wrote in an open appeal to Alabama’s congressional delegation. “Not for new jobs, but for solving an old problem that still exists. That problem hangs over all of Alabama, like a knife to your throat: the coal ash dump that sits next to Mobile Bay. No one should forget what the Tennessee coal ash dump did to that state. A breach of the Mobile site would clearly damage Mobile Bay for decades.”

Thomas believes Bronner’s assessment is on target.

Cade Kistler, Mobile’s Baykeeper, said it’s important to remember that environmental harm can lead to economic pain, too, for individuals and businesses alike.

“There would be a huge impact on the people that want to fish in Mobile Bay and use it for their livelihoods,” he said. “And there are also those people that live on its shores—a lot of beautiful homes and properties. Those Zillow listings won’t look quite so good if a coal ash breach occurs.”

Kistler also pointed out that BP’s 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, which crippled the Gulf Coast environmentally and economically, involved about 134 million gallons of oil, 20 times less than the volume of coal slurry disposed of at Plant Barry. Those who lived through the aftermath of the oil spill on the Gulf Coast remember the deep impact it had on coastal communities.

A coal ash breach could be even worse, Thomas said.

“If a breach occurred, we would be the most industrially polluted site in the nation, and we know that pollution wouldn’t just go away,” she said.

That’s why she and Wilson have committed themselves to informing others across the state about the dangers of the waste, something they now do in memory of Smith, who died of cancer in October 2023.

“Sallie’s focus was on connecting people in search of our common humanity, and in seeking to deepen our understanding and compassion for one another,” her obituary read. “This ardent effort was an outgrowth and demonstration of her deep faith. She loved her family, Mobile Bay, country music, her many friends, including her hiking group of intrepid college friends, and all God’s people.”

“Pray We Don’t Have a Hurricane”

While there’s still much to be done to contain the coal ash threat, Thomas said, there have been at least some glimmers of hope. In early 2024, Alabama Power confirmed a plan to contract a company called Eco Materials to remove and recycle some of the coal waste stored at Plant Barry.

Since then, however, there has been little in the way of substantive public updates about the project, which company officials previously said would begin recycling coal ash into construction materials like concrete in January 2026. In response to an inquiry from Inside Climate News, a representative for Alabama Power said the recycling facility is “expected to be in service by early 2026.”

Eco Materials was acquired by materials company CRH in July 2025, according to an announcement. Neither Eco Materials nor CRH responded to a request for a detailed update on the recycling plans.

Still, Thomas said that even the conception of a plan is a step in the right direction.

“We need to recycle as much as possible and just pray we don’t have a hurricane,” she said.

Kistler said he fears just that. An extreme weather event or other emergency could leave a world-renowned environmental gem drowned in polluted sludge.

Alabama Power’s emergency action plans, bare-bones documents required by federal law, provide only limited information about what could occur if a breach happened at its coal ash sites across the state. The documents also provide little real-world information about how the company would approach mitigation, clean up and remediation.

Regarding extreme weather, the 39-page emergency plan for Plant Barry mentions only that if severe weather causes road closures during an emergency dam breach, company response times may be delayed. Despite Plant Barry’s location in south Alabama, the word “hurricane” does not appear in the emergency action plan.

“It’s foolhardy,” Kistler said. “There needs to be more detail.”

Regulators have agreed. In January 2023, the EPA issued Alabama Power a notice of potential violation informing the company that, in the agency’s view, it had violated federal regulations because its groundwater monitoring program and emergency action plan were not adequate.

The agency settled that dispute with Alabama Power in 2024 when the company agreed to “evaluate and expand its groundwater monitoring program at Plant Barry, to review and upgrade its Emergency Action Plan, and to pay a civil penalty of $278,000,” according to the EPA.

More than a year later, a representative of the utility told members of Alabama’s Public Service Commission that an updated emergency action plan is still in the works.

“The emergency action plan will be modified to include additional wording and descriptions to clarify the company’s preparedness for extreme weather conditions,” Dustin Brooks, land compliance manager for Alabama Power, told commissioners on Dec. 9.

“I just hope that outside this public document, they’ve got better plans somewhere,” Kistler said.

A previously available copy of the EPA’s settlement agreement with Alabama Power has been removed from the agency’s website, though the press release announcing the agreement remains. “This Initiative is needed given the breadth and scope of observed noncompliance with the federal coal ash regulations,” the agency said.

An executive of Alabama Power, which owns most of the state’s coal ash units, claimed at a September 2023 EPA hearing that the utility’s storage ponds are “structurally sound.” Susan Comensky, Alabama Power’s then-vice president of environmental affairs, told EPA officials that allowing the company to “cap” coal ash waste in place, even in unlined pits, will not present significant risks to human or environmental health.

“Even today, before closure is complete, we know of no impact to any source of drinking water at or around any Alabama Power ash pond,” Comensky said at the time.

However, Alabama Power has been repeatedly fined for leaking coal ash waste into groundwater.

In 2019, the Alabama Department of Environmental Management (ADEM) fined the utility $250,000 after groundwater monitoring at a disposal site on the Coosa River in Gadsden showed elevated levels of arsenic and radium, according to regulatory documents.

In 2018, ADEM fined Alabama Power a total of $1.25 million for groundwater contamination, records show. In its order issuing the fine, the agency cited the utility’s own groundwater testing data, which showed elevated levels of arsenic, lead, selenium and beryllium.

Plant Barry is just one of Alabama Power’s six plant sites across the state that store coal ash. In all, the slurry lagoons cover a footprint of around 2,000 acres and pose unique risks to groundwater and waterways around them.

A now capped-in-place coal ash impoundment at Plant Gadsden, for example, is still contaminating groundwater more than seven years after its closure, according to Alabama Power’s groundwater monitoring reports and a lawsuit filed against the utility by Coosa Riverkeeper, an environmental nonprofit.

“The citizens of Gadsden and folks who depend on Neely Henry Lake deserve so much better than Alabama Power’s legacy of pollution,” Justinn Overton, executive director and riverkeeper at Coosa Riverkeeper, said in a news release after the lawsuit was filed. “Drinking water supply, booming ecotourism, and hard-working Alabamians are all threatened by Alabama Power’s recklessness.”

In a motion to dismiss the lawsuit over groundwater contamination at Plant Gadsden, lawyers for Alabama Power emphasized that state regulators approved the company’s plans for coal ash waste at the site.

When groundwater monitoring identified elevated levels of contaminants, the lawyers wrote, “Alabama Power worked with professional engineers and the public to design and implement a corrective action program to address those exceedances—a program certified as compliant with the federal CCR rule and that will continue as part of ‘post-closure care.’”

While the suit should be dismissed due to an expired statute of limitations, Alabama Power’s attorneys argued, the court should also decline to second guess the decision of state regulators to approve the company’s actions.

“[Coosa Riverkeeper] asks the Court to turn back the clock, to before 2020, to second-guess the groundwater monitoring system and closure decisions—work completed long ago, approved by state regulators, and certified by professional engineers as compliant,” the motion said.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

Plants Barry, Gorgas, Greene County and Miller have been designated as having “significant hazard potential” under federal law. Plant Gaston, located near the town of Wilsonville in Shelby County, has been designated as having “high hazard potential.”

Following an emergency dam break at that site, which the company deems “unlikely,” Alabama Power’s initial hazard potential assessment concluded that “water and [coal ash] could potentially impact the residential neighborhood to the west, and the Coosa River to the south…failure or misoperation of the [coal ash] unit could potentially result in a loss of human life.”

Kistler said that it’s notable that Alabama Power is unique among southern utilities in leaving all of its coal waste in unlined pits along waterways. Georgia Power, another subsidiary of Southern Company, has already shifted toward more appropriate disposal of at least some of its coal ash in lined landfills. It’s not a question then, Kistler said, of whether Alabama Power can do the same. It’s only a question of if it will.

“It feels like we’re paying premium prices, and we’re getting bargain-bin environmental protections,” he said, making a reference to Alabama Power’s highest average residential electric bills in the nation. “If Georgia can do it, why not us?”

A Coal Legacy and a Fossil-Fueled Future

Barry Brock, with the Southern Environmental Law Center, is part of the team of lawyers suing Alabama Power over its coal ash impoundment at Plant Barry. Initially dismissed by a Trump-appointed U.S. district court judge on technical grounds, the case is now pending before the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals, where Brock said he is hopeful the team will secure a victory.

Oral arguments in the case were held in Atlanta in November, and some of Alabama Power’s arguments were unusually revealing, Brock said.

“Alabama Power admits that a lot of the coal ash is going to be left in contact with groundwater under their closure plan,” he said. “That’s particularly galling.”

Coal ash isn’t SELC’s first legal tussle with Alabama Power, however. Lawyers for the environmental nonprofit are also representing customers suing Alabama Power over residential solar fees they argue violate the law and discourage the use of renewable energy. In response, the company has said that it “support[s] customers interested in using onsite generation, such as solar” but that its rate structure for those customers must avoid “unfairly shifting” costs to other ratepayers.

Meanwhile, the company has doubled down on its fossil fuel investments, purchasing a natural gas plant in Autauga County for around $622 million, effectively locking the company into the continued use of fossil fuels for years to come, though the company said in an email that its investments are data-driven, forward-looking and “are not based on a preference for any one fuel source.”

All of these developments are individually concerning, Brock said, and together, they demonstrate a pattern.

“It sends a pretty clear message that Alabama Power is really concerned about their financial well-being and the rate of return they get on fossil fuel infrastructure,” he said. “It says they have a pretty compliant regulatory environment that is not going to scrutinize them when they want to raise rates for customers to do it.”

While the company clearly has the resources to line its coal ash ponds and recycle much of the waste, there’s also little doubt that the state can count on much more sympathetic federal regulators under the Trump EPA than it did under Democratic leadership. At present, the state and federal governments seem closely aligned: Twinkle Cavanaugh recently resigned after 13 years as president of the state’s Public Service Commission, the agency charged with regulating Alabama Power. Her new position: a job as the Trump administration’s top Department of Agriculture official in Yellowhammer State.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,