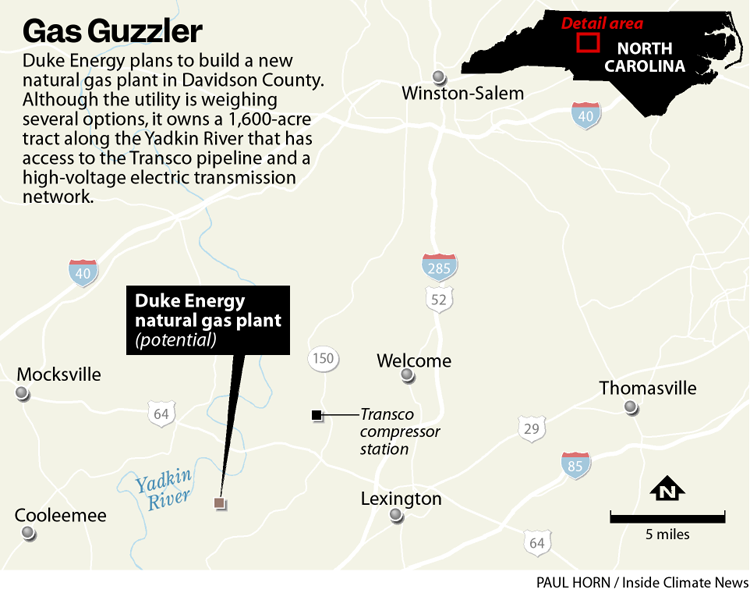

Duke Energy could build a 1,360-megawatt natural gas power plant on company-owned land in western Davidson County, which, if approved by the N.C. Utilities Commission, would add tons of climate-heating greenhouse gases into the air each year.

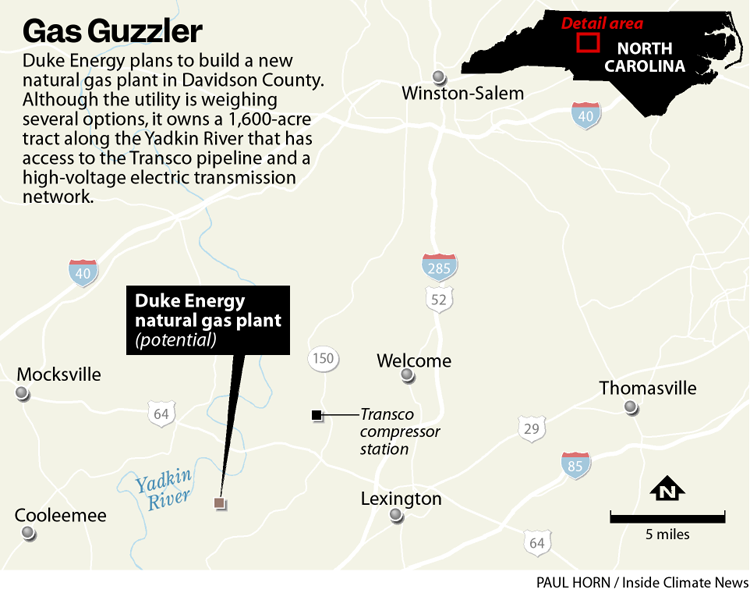

The 1,600-acre site at 3714 Giles Road is about eight-and-half miles west of Lexington and abuts the Yadkin River.

Duke Energy spokesman Bill Norton said the company has “made no final decision regarding the location of the next combined cycle facilities,” and “has considered multiple potential sites in multiple counties.” Combined cycle facilities use both gas turbines and steam turbines to increase efficiency.

Duke’s revised Cluster Study Phase 1 report, dated December 2025, specifies that a natural gas project, known as CC4—which stands for Combined Cycle 4—could be built in Davidson County. Potential sites for CC4 have not been previously reported.

A summary on the utility’s website also notes a plan for another plant, CC5, whose location is not listed.

Both projects would require Utilities Commission approval.

Large natural gas plants require hundreds of acres of land, which narrows Duke’s options. The North Carolina Electric Membership Corp. owns a 430-acre tract near the Transco natural gas compressor station northwest of Lexington that is large enough to accommodate such a facility.

But an NCEMC spokesman told Inside Climate News the cooperative “has no project planned” for the site.

The NCEMC is an electric cooperative that buys electricity from Duke and other wholesalers and provides power to its two-dozen member cooperatives. NCEMC also owns a stake in several of Duke’s nuclear and natural gas plants, including another new natural gas unit under construction in Person County.

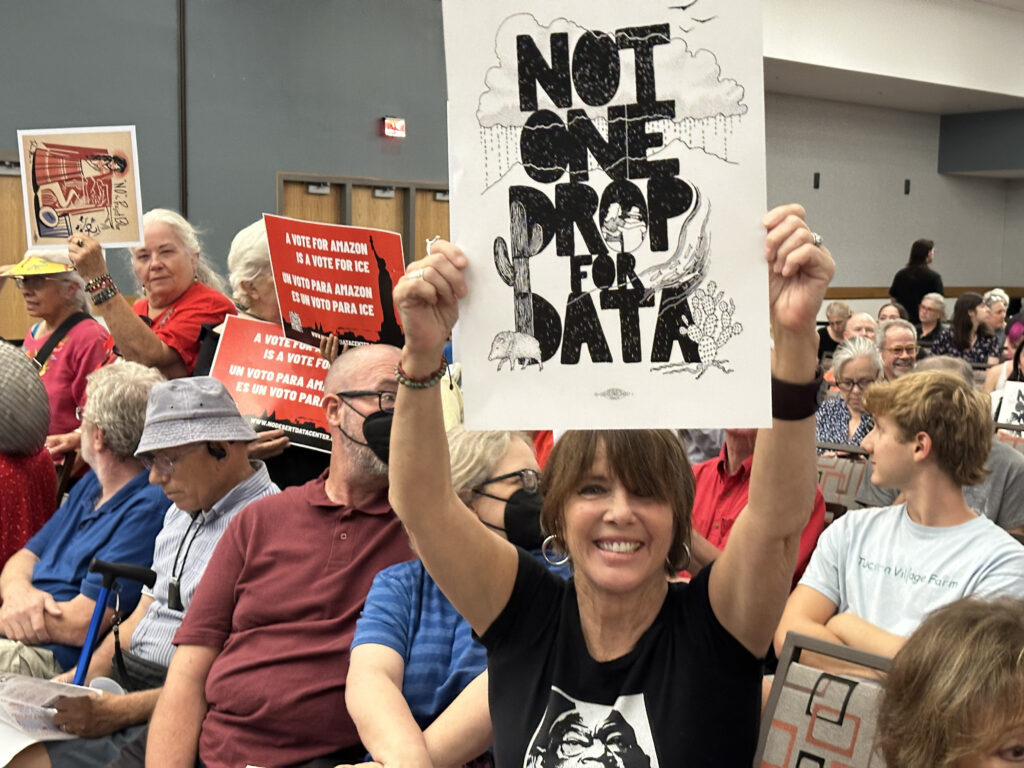

Maggie Shober, a transmission expert and research director with the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy, uncovered the potential Davidson County sites. Environmental advocates and the public usually learn of major energy projects only after utilities have announced them. By that point, the companies have already prepped regulators behind the scenes, Shober said, which puts opponents at a disadvantage.

“Having as much information as we can—and as early as we can—is really important,” Shober said. “We have huge concerns with this project.”

Duke has attributed the need for more energy—including solar, battery storage, nuclear power and natural gas—to the proliferation of data centers, which are voracious consumers of energy, as well as to new manufacturing plants, the growth of the life science industry and population increases.

The potential Davidson County plant is part of a vast natural gas expansion in North Carolina that includes pipelines, compressor stations and a liquified natural gas facility.

But unlike Duke’s seven other proposed natural gas plants, which would be co-located at existing facilities, the Davidson County project would be built on undeveloped agricultural and timber land.

“These two different types of land use simply are not compatible,” said Shelley Robbins, the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy’s senior decarbonization manager. “It will be expensive, it will be loud, it will be ugly, it will be huge, it will pollute, and it will require water resources, likely from the nearby Yadkin River, that will no longer be available for agriculture.

“And it isn’t even needed. All this complex will do is turn methane gas into combustion pollution and move money from ratepayers’ pockets into shareholders’ portfolios.”

Duke purchased the Giles Road property in 1995 from the company’s former real estate division, Crescent Resources, according to county deed records.

Crescent Resources is a legacy of the utility’s previous foray into land development. In the 1960s, Duke Energy acquired approximately 300,000 acres of land in rural North and South Carolina, according to court records. In 1969, the utility contributed the acreage to the Crescent Land and Timber Co., which became a real estate company, Crescent Resources, a Duke subsidiary.

Duke is no longer affiliated with Crescent.

In addition to land, natural gas plants are often located close to pipelines in order to access the fuel. Transco’s 10,000-mile interstate pipeline traverses across the southeastern corner of Duke’s property, according to maps analyzed by the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy. Two high-voltage transmission lines also run three to four miles from the tract.

Transco is also expanding 10 miles of the pipeline as well as a compressor station in central Davidson County, near Lexington.

The site’s proximity to the Yadkin River could also provide the necessary cooling water for the facility.

Natural gas plants emit less carbon dioxide than coal-fired units but release exorbitant amounts of methane, a greenhouse gas that is over 80 times more potent in heating the atmosphere over a 20-year period. In addition to carbon dioxide, burning natural gas also releases hazardous and toxic air pollutants that can harm local communities.

Duke’s Asheville Combined Cycle Station, which burns natural gas, emitted 1.1 million tons of greenhouse gases in 2023, as measured by carbon dioxide equivalent, according to U.S. Environmental Protection Agency data. A carbon dioxide equivalent is a unit of measurement that accounts for the varying global warming potential of different greenhouse gases.

The Asheville plant is relatively small, with a generating power of just 560 megawatts; CC4’s would be two-and-half times greater.

Natural gas infrastructure—plants, pipelines, compressor stations and liquified natural gas (LNG) facilities—also emit other air pollutants, including fine particulate matter and volatile organic compounds. Parts of Davidson County already rank among the 80th to 90th percentile for toxic air pollutants, as compared to federal and state exposures, according to the EPA’s EJScreen.

Several major state and federal policy decisions have incentivized the continued use and growth of fossil fuels. Last July, the Republican-majority state legislature passed Senate Bill 266, which eliminated Duke’s interim decarbonization goal of 70 percent by 2030. The utility still has a benchmark of net-zero by 2050.

Democratic Gov. Josh Stein vetoed the bill, but the legislature overrode it.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

The law also allows the utility to pass its financing costs of new energy projects, including natural gas and nuclear, onto ratepayers before the units are built.

The new plants will hike customers’ bills in two main ways, Shober said: through the costs of construction, which can increase over time, and the gas, whose price is unpredictable.

“Even if Duke were somehow able to keep the construction costs contained, they’re locking customers into fuel costs for decades to come,” she said.

Under state law, every two years Duke must file with the state Utilities Commission an updated CPIRP, short for Carbon Plan and Integrated Resource Plan. It lays out the proposed energy mix, demand and costs projections, including the impacts on ratepayers. The commission can approve, amend or deny it.

The commission will hold the first public hearing on the latest plans on Feb. 4 in Durham. The commission is scheduled to rule on the CPIRP by the end of the year.

Duke Energy’s 2025 carbon plan devotes several pages to enhanced liquified natural gas, known as ELNG. While traditional LNG is used to meet peak energy demand, such as during extremely hot or cold days, ELNG is more nimble. The technology allows utilities to access the gas during off-peak times to balance daily and hourly supply and demand.

This requires access to the gas via a pipeline and the construction of enormous holding tanks.

The 485-acre Moriah Energy Center under construction in Person County will be a traditional LNG plant operated by Enbridge. It will have at least one 25-million-gallon storage tank, with room for a second. The center will emit as much as 64,000 tons of greenhouse gases, according to company estimates, but also carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxide and hazardous and toxic air pollutants.

It is unclear if a Davidson County site would include ELNG.

“Any projections about price, fuel supply or storage capacity” at CC4 and CC5 would be “premature,” Norton said.

There is not a firm timeline for when Duke could formally announce the locations of CC4, CC5 and its plans for ELNG. The two plants could be operating as soon as 2032 and 2033, respectively, according to utility documents.

The Trump administration has incentivized fossil fuel production and generation while stripping incentives from—or attempting to halt altogether—renewable energy projects. President Donald Trump has also announced his intention to withdraw from international agreements intended to combat climate change.

This week, the EPA announced it would amend Clean Water Act regulations to limit the authority of states and tribes to regulate water quality through their respective permitting processes. The purpose, the EPA said: to streamline the permitting process for large energy projects, including pipelines and natural gas infrastructure.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,