Coal power took a big step toward the exit last year in the United States, as plants continue to close and the ones that remain are being used less than before.

While we’re still a decade—or maybe decades—away from the shutdown of the last U.S. coal plant, the fuel’s role in our energy economy has probably diminished past the point of no return.

This is good for the climate and human health, considering that coal does grave harm through emissions of planet-warming carbon dioxide, along with toxins like sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide.

We’re hiring!

Please take a look at the new openings in our newsroom.

See jobs

But replacing coal’s contributions to a reliable grid will be a challenge, albeit a challenge policymakers and energy analysts have seen coming.

Some numbers to help understand this moment:

- Coal-fired power plants generated 16.2 percent of the country’s electricity in 2023, a decrease from 19.7 percent in the prior year and down about half from a decade ago, according to the Energy Information Administration. The decline was largely due to utilities and grid operators relying more on natural gas power plants, which are much cheaper to build and operate than coal plants. The growth of renewable energy also contributed to coal’s retreat, but not nearly as much as the growth of gas.

- The number of coal plants is continuing to fall. The country had 184 gigawatts of capacity of coal-fired power plants in 2023, down 6.4 percent from the prior year, according to EIA. One example is the 1,490-megawatt W.H. Sammis plant in northeast Ohio, which closed after years in which its owner, Energy Harbor, and the previous owner, FirstEnergy, let it sit idle most of the time.

- As the number of coal plants continues to shrink, plant owners are using the remaining ones less than before. This can be seen by looking at the average “capacity factor” of coal plants, which is a comparison of actual electricity generation with the maximum possible. The average capacity factor for coal plants last year was 42.1 percent, down from 48.4 percent in the prior year.

The main driver of the move away from coal is that other electricity sources have gotten less expensive, said Melissa Lott, an engineer and senior director of research at the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University.

“Most of this has been driven by natural gas replacing coal,” she said. “Some of it is increasingly about renewables replacing coal. It’s the economics of it—that stuff is cheap, so you use it. And it’s less carbon intensive, which is really good from a climate perspective.”

(Lott testified before the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources last year about how to maintain reliability as coal fades from the picture.)

I should mention that some coal-producing states, such as Wyoming and West Virginia, have adopted policies and taken regulatory actions that seek to keep coal plants open for as long as possible. The plants that are likely to hang on for the longest are those that are relatively young and are located in a coal-friendly state. A good example is Dry Fork Station in Wyoming, which opened in 2011 and is also unusually competitive for a coal plant.

Gas is plentiful because drillers have been able to harness new supply from shale deposits throughout the United States. Gas became the country’s leading fuel for producing electricity in 2016 and has continued to increase its market share, making up 43.1 percent of U.S. electricity generation in 2023.

People in the gas industry have argued that their product is part of the solution to climate change because burning gas releases less carbon dioxide than burning coal, when measured per unit of energy. But that requires ignoring a bunch of other issues, such as the effects of methane leaks from the gas supply chain.

To get to near-zero emissions, which is needed for the world to avoid the most harmful effects of climate change, gas plants are going to need to go through their own wave of closings.

Here’s the really tough question: How can the United States and the world have a supply of electricity that is reliable enough to meet our needs and affordable enough to support a vibrant economy, while also being clean enough to address climate change?

Lott refers to these needs as “the trifecta.”

“Reliable, affordable and clean power,” she said.

Coal is reliable. For a long time, it was affordable. But it’s never been clean.

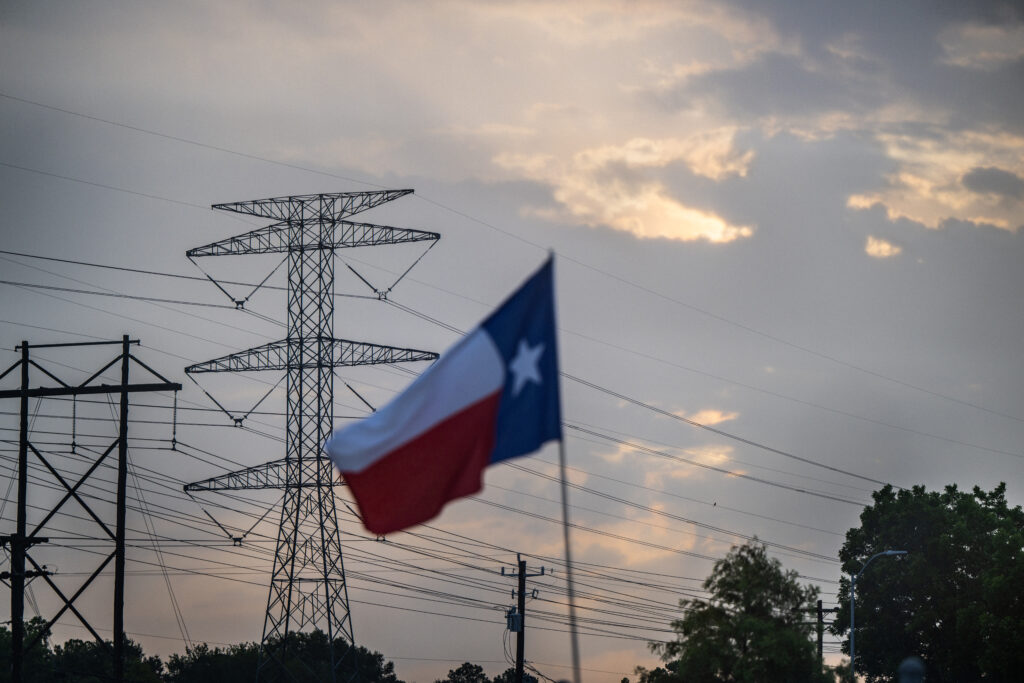

Gas is reliable much of the time, but has a tendency to fail in extreme weather, as Texas has seen in recent years. It has been affordable lately, but has a long-term history of price volatility. It’s cleaner than coal in some ways, but it’s not clean.

Some power sources have a lot of appeal in terms of achieving the trifecta, if they can find ways to reduce costs. An obvious example is nuclear power, which is reliable and mostly clean, but has suffered from decades of missteps with projects that went grossly over budget. Another impediment to nuclear power is concern about safety, including the potential for accidents that would release radioactive material and the questions about where to store spent nuclear fuel.

Geothermal power, now a fraction of 1 percent of the country’s electricity generation, has the potential to substantially increase its share.

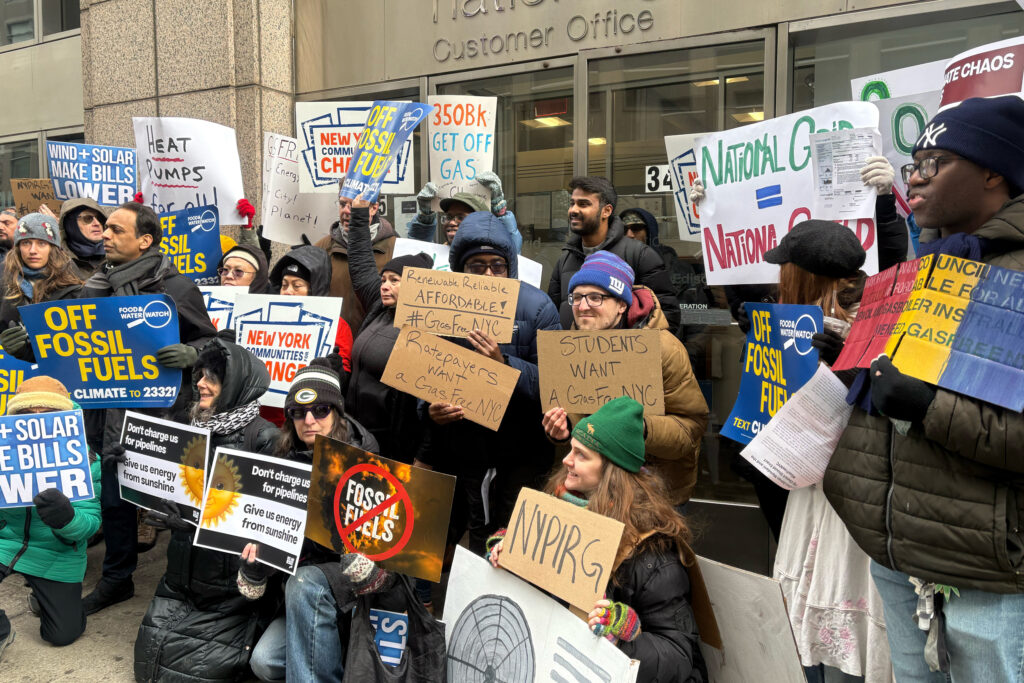

Where do wind and solar fit into this conversation? Ideally, the mass deployment of wind, solar and energy storage will be able to provide a result, from the consumer’s perspective, that feels almost indistinguishable from the mix of power sources we have today. But renewables are going to need lots of help, including a major increase in interstate power lines.

The larger point is that a variety of resources are going to need to grow a lot to pick up the slack of coal—and fast.

Other stories about the energy transition to take note of this week:

How China Came to Dominate the World in Solar Energy: China installed more solar panels last year than the United States has in its history, and China’s solar growth shows signs of continued acceleration, as Keith Bradsher reports for The New York Times. China’s leaders said that a “new trio” of industries—solar panels, electric cars and lithium batteries—has replaced an “old trip” of clothing, furniture and appliances.

Rivian Gives a First Look at Two Upcoming Models: Rivian, the U.S.-based manufacturer of electric trucks, had the automotive press abuzz last week at an event in California that offered a first look at two upcoming SUVs, the mid-size R2 SUV and the compact R3. The R3, which will make its debut later with a 2027 model year and a price point expected to be in the $35,000 to $40,000 range, has the potential to be a breakthrough vehicle. Eric Stafford of Car and Driver has a rundown on the R3 and a derivative model, the R3X.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

… and Rivian Pauses Plans for a Georgia Factory: The event for the R2 and R3 included an announcement that Rivian is pausing plans to open a Georgia factory. The company said it still intends to open the Georgia factory, with a projected investment of $5 billion, but is going to delay the plans to allow for a faster rollout of new models that will be assembled at an existing factory in Illinois, as Jeff Amy and Russ Bynum report for the Associated Press. Rivian did not give a timetable for when it would resume work on the new plant. This is a blow to Georgia, which will need to wait for the investment and a projected 7,500 jobs. But it may be good in the short term for Rivian, saving the company some money and allowing it to focus on the launch of the new models.

Where Electric Vehicles Are (and Aren’t) Taking Off Across the U.S.: EVs have reached the mainstream in some parts of the country and remain a rarity in others, as Nadja Popovich reports for the New York Times. The leading metro areas for EVs are in California, led by San Jose, where about 40 percent of new vehicle registrations are for electric models. At the bottom is McAllen, Texas, where the EV share remains in the low single digits.

How Changes to Hawaii’s Home Battery Program Could Hinder the State’s Clean Energy Transition: Hawaii’s main utility is launching a new program to encourage customers to get energy storage systems, but the compensation is much less than what customers now receive under an earlier battery program. Clean energy and environmental organizations are raising concerns that the shift is going to be harmful to Hawaii’s push to use only clean energy by 2045, as Gabriela Aoun Angueira reports for Grist. The discussion in Hawaii is similar to what is happening in other states as policymakers and utilities are trying to balance costs with the need to rapidly increase use of solar and storage.

Inside Clean Energy is ICN’s weekly bulletin of news and analysis about the energy transition. Send news tips and questions to [email protected].