Canada’s tar sands have gained infamy for being one of the world’s most polluting sources of oil, thanks to the large amounts of energy and water use required for their extraction. A new study says the operations are also emitting far higher levels of a range of air pollutants than previously known, with implications for communities living nearby and far downwind.

The research, published Thursday in Science, took direct measurements of organic carbon emissions from aircraft flying above the tar sands, also called oil sands, and found levels that were 20 to 64 times higher than what companies were reporting. Total organic carbon includes a wide range of compounds, some of which can contribute directly to hazardous air pollution locally and others that can react in the atmosphere to form small particulate matter, or PM 2.5, a dangerous pollutant that can travel long distances and lodge deep in the lungs.

The study found that tar sands operations were releasing as much of these pollutants as all other human-made sources in Canada combined. For certain classes of heavy organic compounds, which are more likely to form particulates downwind, the concentrations were higher than what’s generally found in large metropolises like Los Angeles.

We’re hiring!

Please take a look at the new openings in our newsroom.

See jobs

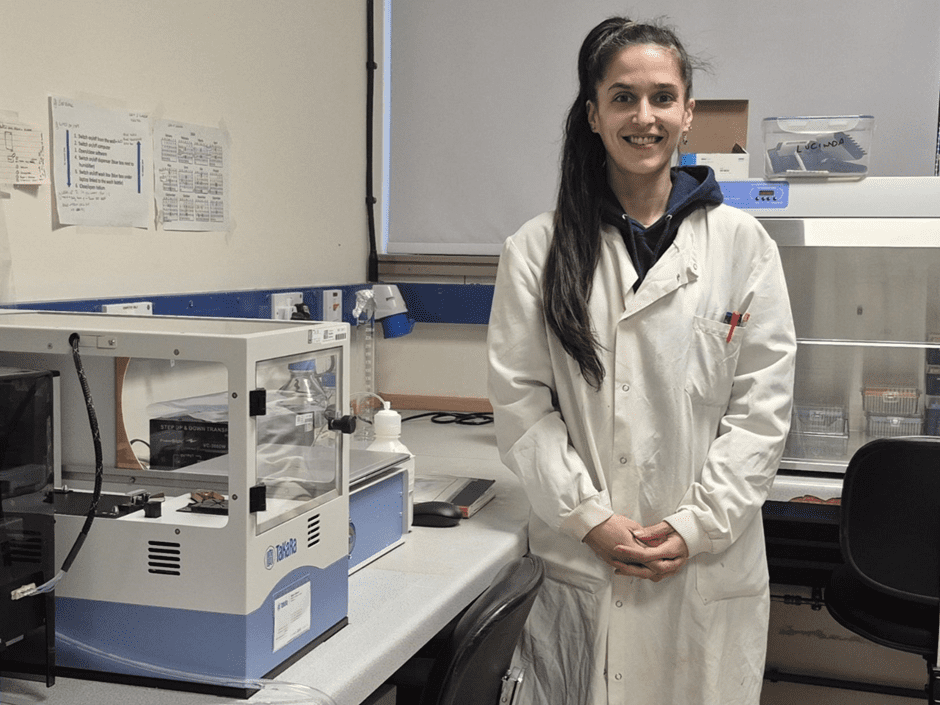

“The absolute magnitude of those emissions were a lot higher than what we expected,” said John Liggio, a research scientist at Environment and Climate Change Canada, the nation’s environmental regulatory agency, and a co-author on the study. Researchers at Yale University also contributed.

Seth Shonkoff, executive director of PSE Healthy Energy, an independent scientific research institute in California, who was not involved in the study, said the findings suggest air pollution from tar sands operations is more damaging to people’s health than previously known.

“I actually could hardly believe what I was reading,” Shonkoff said of the new study.

Over the last decade, a growing body of research has examined emissions of different air pollutants from oil and gas operations across the United States and Canada, and much of that has shown that industry estimates tend to undercount what’s being released, he said. “But the scale of this discrepancy is very surprising.”

Mark Cameron, vice president of external relations at the Pathways Alliance, an oil sands industry group, said in an email that the findings warrant further review and that “the oil sands industry measures emissions using standards set by Environment and Climate Change Canada and we look forward to working together to explore opportunities to further enhance our measurement practices.”

Canada’s oil sands stretch across a large area of northern Alberta and are one of the world’s largest deposits of crude. Canada is the biggest source of oil imports to the United States and most of that petroleum comes from the oil sands.

The deposits do not technically hold crude oil, but instead a heavier hydrocarbon called bitumen, which must be heated and treated in order to form a liquid that can be piped and refined like oil. That process requires sprawling industrial operations of open pit mines, ever-growing waste ponds and refinery-like “upgraders.” The waste ponds have leached toxic chemicals into groundwater, and a heavy, sulfurous stench often settles over the region. The mines have stripped away an area larger than New York City, lands that had long been occupied by people from several Indigenous First Nations. One of those First Nations, Fort McKay, is now surrounded by mines.

Some bitumen is extracted using a system of wells that inject steam to effectively melt the hydrocarbons underground before pumping them to the surface, known as “in-situ” extraction.

The study found that both types of extraction released comparable levels of air pollutants relative to their size.

The study emerged from earlier work, published in 2016 by some of the same researchers, which found high levels of particulate pollution downwind of the oil sands. That study left the question of what exactly was being emitted by the mines to form these particulates, Liggio said, and whether those emissions could explain that downwind pollution.

“The short answer to that question is yes,” Liggio said.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

Liggio said the findings suggest that scientists and regulators do not have a proper understanding of air pollution across the region. Because it is impractical to measure all pollutants across large areas, he said, regulators often rely on modeling to estimate air quality. The models rely on inventories different industries use to report their emissions, and “you need to get the inputs into that model correct,” Liggio said. “What we’re showing here is that the emissions are not fully correct, they’re higher than what’s currently in the inventories, which by extension means that if you’re trying to model the impacts, the exposure, et cetera, you’re probably not going to get that right either.”

The paper did not try to assess the health impacts of the pollution it measured. But Liggio said the findings could have implications beyond the region. The organic compounds the researchers measured tend to linger in the air for only a day or less, he said. But the most surprising finding was that there were much higher levels of heavy organic compounds, which are much more likely to react in the atmosphere and form particulate matter. Once formed, those particles can then hang in the air for weeks and travel hundreds or thousands of miles—they are the same type of pollutants that Canadian wildfires sent across the continent last summer, blanketing cities in the eastern United States.

The paper also raised questions about methods for disposing of the toxic “tailings” that are left over after extracting bitumen from the mines. This solid waste has been accumulating in water-filled lagoons, which by 2020 had swelled to cover an area nearly twice the size of Manhattan. Remediating these pits has proven to be extremely difficult, and laboratory tests conducted by Liggio and the researchers suggest that some novel efforts for separating solids from liquids could release even more pollution-forming compounds into the air.