Cameron, La.—Ray Mallett started fishing near the mouth of the Calcasieu River more than half a century ago as part of the “mosquito fleet,” a ragtag group of kids that plied the surrounding rivers and bayous in small motorboats in search of crabs.

A Gulf Coast fisherman like his father before him, Mallett harvested shrimp for decades from an estuary in Southwest Louisiana that was once the seafood capital of America.

Now, he can hardly catch enough shrimp to pay for fuel.

“Each year we’re getting less and less,” Mallett said, standing at the helm of his boat, Cajun Memories. The name is a nod to his roots, and as one of the last remaining shrimp boats in Cameron’s port, a once-thriving fishery.

Harvests from the Calcasieu River, where shrimp migrate each year to spawn, have declined for decades as chemical plants and refineries located farther upstream have polluted the Calcasieu, making it one of the country’s most endangered rivers.

Catches dropped even further in recent years and Mallett, along with an increasingly vocal group of fishermen, has theories about why.

It’s “because of the goddarn plant,” said Mallett, a slight but sinewy 63-year-old with a grey goatee and the image of Jesus wearing a crown of thorns tattooed on his forearm.

The plant he’s referring to is Venture Global’s Calcasieu Pass, a sprawling 432-acre liquefied natural gas terminal at the mouth of the Calcasieu River. The export terminal has loaded hundreds of ocean-going vessels with LNG fuel since operations began in 2022, helping to make the U.S. the world’s largest exporter of LNG. But the facility also brought noise and pollution; according to local fishermen, the industrial activity drives off shrimp.

“The shrimp don’t want to cross that barrier for some reason,” Mallett said.

“If there’s not many that come in to spawn, to have babies that go back out, you’re gonna get less and less each year,” Mallett added. “And that’s exactly what happened.”

Jeffrey Plumlee, a researcher at Louisiana State University and a fisheries extension specialist for Louisiana Sea Grant, said much remains unknown about the impact of the construction and operation of the terminals.

“The impact of LNG, specifically, these plants, has not been measured,” Plumlee said. “We don’t really have any great answers.”

Phillip Dyson grew up fishing alongside Mallett. He quit school at 13 to become a shrimper and has fished the inland waters of the Calcasieu River for the past 50 years. Before the plant was built, his boat brought in $125,000 to $175,000 per year. In 2023, Dyson said he made less than half that. Last year, he barely made enough to survive.

“Every year it drops and drops,” said Dyson, 63, standing next to one of his family’s shrimp boats, Papa’s Shadow, which is overdue for repainting and maintenance that Dyson says he can no longer afford. “If it wasn’t for Social Security, I’d go bankrupt.”

An average of 1.5 million pounds of shrimp were harvested from the Calcasieu Basin each year between 2015 and 2024, according to Peyton Cagle, the marine fisheries operations program manager for the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. The figure dropped to just 750,000 pounds in 2024, or half of the 10-year average, he said.

However, Cagle said the changes in the harvest cannot be attributed to a single cause.

“Lower dockside prices, increased expenses, market competition from imported shrimp, and a reduction in the fleet are some of the reasons for the decline in landings,” Cagle said in a written statement.

While shrimp harvests were down 50 percent in the Calcasieu Basin in 2024, they also declined by an average of nearly 30 percent across all of coastal Louisiana last year, Cagle added.

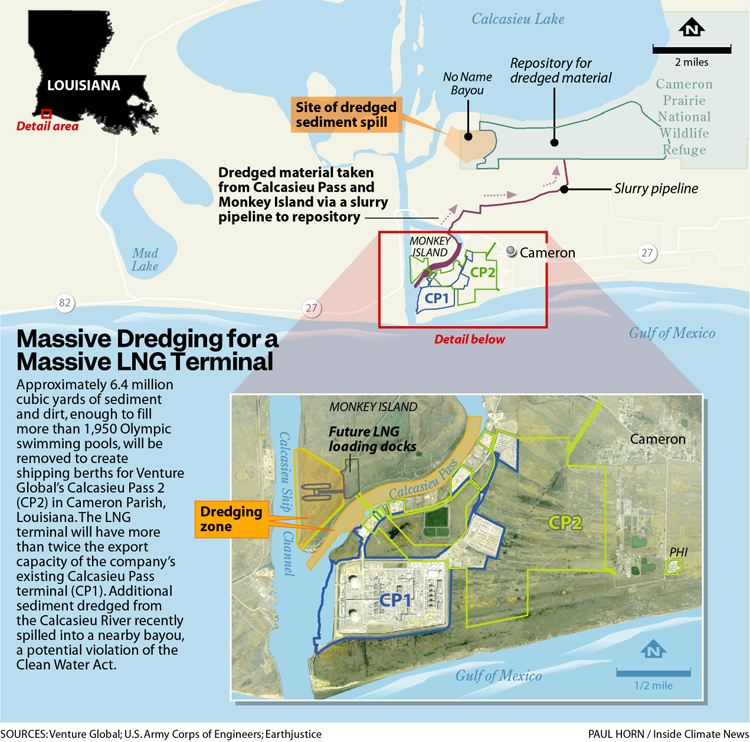

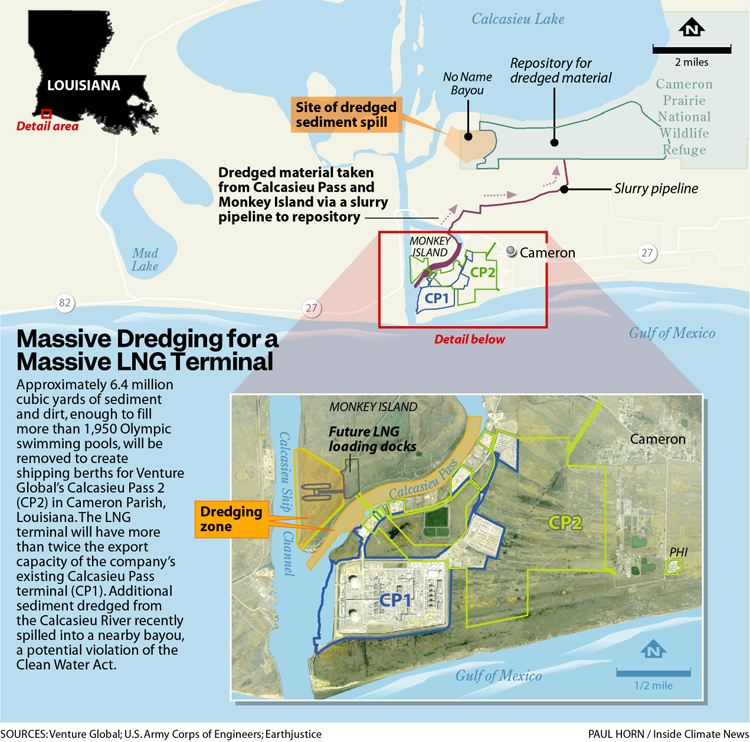

Venture Global is now building Calcasieu Pass 2, a second LNG terminal adjacent to its existing facility, which will have double the export capacity. The plant is part of a massive expansion of new LNG terminals along the Gulf Coast, which will more than double America’s already world-leading export capacity.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which regulates natural gas projects and has approved more than 99 percent of all project applications in recent decades, authorized construction for Calcasieu Pass 2 in June 2024.

However, the decision wasn’t unanimous.

The project’s adverse environmental and local economic impacts “are so great that I am compelled to find that approving the project is inconsistent with the public interest,” Allison Clements, a former FERC commissioner, wrote in her dissent just days before her four-year term at the agency ended.

“The Order improperly discounts impacts to commercial fishing businesses, which will likely be significant,” Clements added.

Dredging near the terminal is a primary concern noted in FERC’s Environmental Impact Statement for the project.

Approximately 6.4 million cubic yards of material—enough to fill 1,957 Olympic-sized swimming pools—will be excavated to create deep water berths for LNG vessels to dock and turn around at the terminal, according to the commission’s assessment.

Dredging would kick up sediment in the water, which may affect the health of shrimp, fish and other marine species by clogging their gills and reducing dissolved oxygen levels, according to the report.

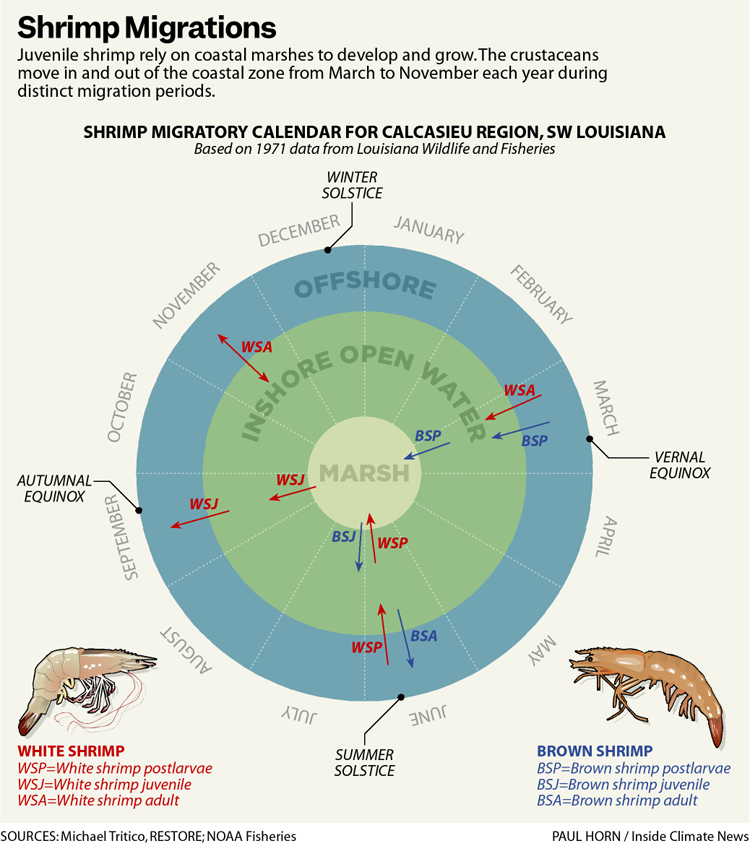

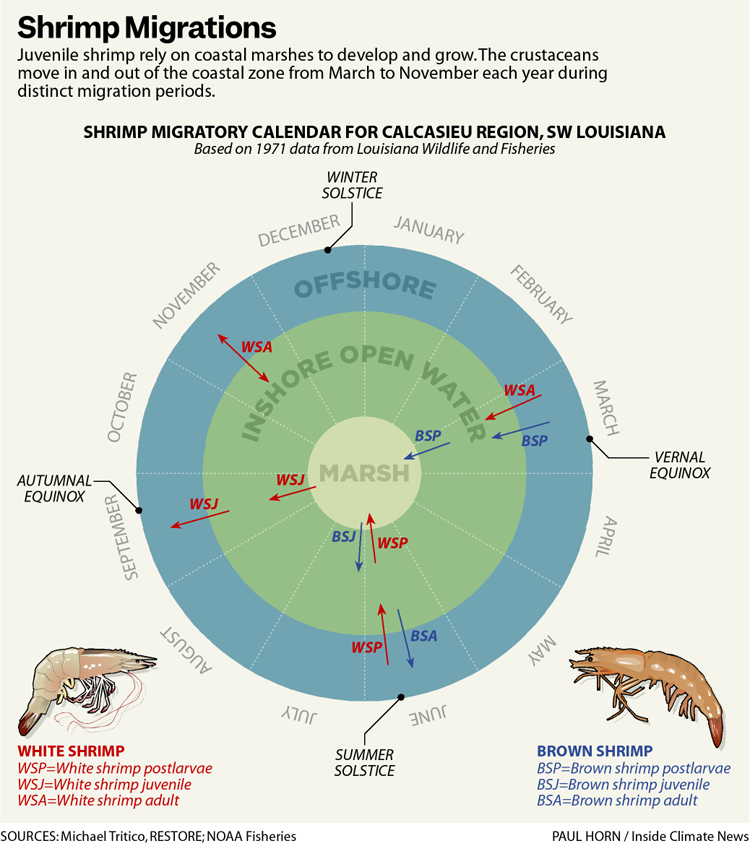

Environmental advocates and state regulators have expressed concern about dredging, particularly during the migration periods for fish and shrimp, which coincide with the spring and fall commercial shrimp harvesting seasons.

In a March 2023 letter to the commission, Randell Myers, an assistant secretary with the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, asked if Venture Global would consider limiting dredging activity to times of year that would not interfere with migration periods for shrimp and other species, as well as commercial fishing.

In its final assessment, FERC noted that the company didn’t anticipate any pauses on dredging during seasonal migration periods. The commission stated that doing so would leave the dredged area exposed to “tidal, wind, and wave action” over a longer period, potentially several months, which could exacerbate sedimentation issues.

Michael Tritico, a former coastal zone manager for southwest Louisiana tasked with protecting and developing the region’s natural resources and an environmental advocate, said not pausing during key migration periods is “the cheap way out.”

“It’s inconvenient and costs more to have the work crew leave and come back later,” Tritico said. “It’s an economic thing, and it’s not a logical scientific argument.”

Venture Global did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Plumlee said shrimp are often referred to as a “year crop” in that they live for approximately one year and their population is replenished annually. Each female shrimp releases up to a million eggs. If even a small portion of the estuary’s shrimp population can migrate in and out of the river mouth, the population will likely remain stable over time, he said.

As long as the resources juvenile shrimp need to develop, including good marsh habitat, tidal water flows and food, remain, “then I foresee them recovering quickly.”

Environmental advocates said the increased ship traffic from additional LNG terminals, not counting any disruptions from the facilities themselves, will have lasting impacts from which the shrimp may never recover.

Venture Global has plans for Calcasieu Pass 3, a third LNG export terminal at the mouth of the Calcasieu River with potential export capacity nearly equal to that of its first two terminals combined. In addition, Commonwealth LNG, an export terminal on the opposite bank of the Calcasieu River from Venture Global’s facilities, received final approval from the U.S. Department of Energy on Aug. 29 and may soon begin construction. Each of these facilities will draw massive oceangoing vessels to the rivermouth.

“They want to [add] six, seven, eight more ships every day,” said James Hiatt, founder of For a Better Bayou, a local environmental and community advocacy organization. “What you’ll have is just an insane amount of ship traffic in a place that is feeling effects of the traffic we already have. At what point is enough enough?”

In February 2023, the Louisiana Shrimp Task Force, an advisory committee to the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, sent a letter to state and federal agencies responsible for permitting Venture Global’s Calcasieu Pass 2 LNG export terminal, warning about the potential impact of this and other proposed LNG terminals.

“This is a radical transformation of the Louisiana coast,” the letter, signed by Acy Cooper, then chairman of the task force and a commercial shrimper, stated. “If successful, this construction and expansion will destroy the shrimping community in Cameron Parish and have serious consequences throughout the State.”

The letter ended with a warning. If the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries waits to assess the damage from gas export facilities until after they are constructed, it “will be far too late.”

Cagle, of the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, said the agency conducts biweekly or monthly monitoring of shrimp abundance and size and has not seen “any alarming reductions” since construction of Calcasieu Pass and Calcasieu Pass 2 began.

“What you’ll have is just an insane amount of ship traffic in a place that is feeling effects of the traffic we already have. At what point is enough enough?”

— James Hiatt, For a Better Bayou

If the department notices any impacts after Calcasieu Pass 2 is constructed, they would initiate an impact analysis at that time, Cagle said.

Since writing the letter, the task force, as well as the Louisiana Shrimp Association, an industry group also headed by Cooper, have focused more on the issue of low-cost shrimp imported to the U.S. from aquaculture farms in Asia.

Imports began in large numbers in the 1990s and have continued to climb, reaching 93 percent of all shrimp consumed in the U.S. in 2024, according to the U.S. International Trade Commission, causing a steep and decades-long decline in the price of U.S.-caught shrimp, according to a federal fisheries report published in August.

The Shrimp Association praised a 50 percent tariff the Trump Administration placed on imports from India, the largest importer of shrimp to the U.S, on Aug. 27. However, the group didn’t comment when President Trump issued an executive order in January lifting a Biden administration pause on U.S. Department of Energy permits for new LNG export terminals, including Calcasieu Pass 2.

LNG terminals require federal approval from FERC and the DOE. A DOE permit for Venture Global’s new facility was issued in March, which, along with FERC approval in May, allowed for construction to begin.

Cooper said the LNG issue hasn’t been on the association’s agenda for a while.

State regulators halted dredging in the Calcasieu River near the proposed CP2 terminal on August 8 after fishermen reported sediment from the project spilled beyond its intended containment area in a nearby wildlife refuge. The dredging was conducted by the Cameron Parish Port, Harbor and Terminal District in conjunction with Venture Global, which funded the project and maintained the pipe used to transport the sediment to the refuge.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

Patrick Courreges, a spokesperson for the Louisiana Department of Energy and Natural Resources, said further dredging would be suspended until state and federal regulators approved a process for collecting and returning the lost dredge material.

For a Better Bayou, and Earthjustice said the spill was impacting crab, oyster and shrimp fisheries and was a potential violation of the Clean Water Act. The organizations submitted a letter to the state department of energy and natural resources and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers last month seeking immediate enforcement action, including civil penalties.

The environmental assessment by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which regulates natural gas projects, also noted that prolonged exposure to elevated noise from dredging, pile driving and other construction activity can interfere with an animal’s behavior, such as “migrating, feeding, resting, or reproducing.”

State and federal permits for the project set limits on noise pollution from the facility’s construction and operation as measured at nearby onshore locations. However, there are no noise limits for the marine environment. Habitat Recovery Project, a local conservation organization that works with local fishermen and women, received a grant from the American Geophysical Union last October to measure noise pollution in the water and its impact on marine life.

The monitoring work will be aided and expanded to assess other potential stressors to fisheries in the Lower Calcasieu River through a grant from the Community Resilience Center at The Water Institute, a research organization based in Baton Rouge and New Orleans.

Alyssa Portaro, executive director of Habitat Recovery Project, said she hopes the projects will provide the scientific data necessary to establish guardrails on LNG developments, such as seasonal restrictions on dredging or time-of-day restrictions on tanker movements, which would reduce the facilities’ impact on shrimp and other marine life.

“That would be a win for me,” Portraro said.

Others are less optimistic.

“This is not an industry that can peacefully coexist,” said Tyson Slocum, director of the energy program for Public Citizen, a nonprofit consumer advocacy organization based in Washington, D.C. “They’ve just gotten started.”

Environmental advocates continue to push back. Commercial fishermen, impacted landowners, and environmental groups are continuing their lawsuit against FERC over its approval of the Calcasieu Pass 2 terminal.

Meanwhile, Earthjustice is challenging the project’s dredging permits issued by the Louisiana Department of Energy and Natural Resources. The Sierra Club and other environmental organizations recently filed suit against the state’s Department of Environmental Quality over the project’s air permits. At the same time, Habitat Recovery Project, the Louisiana Bucket Brigade and the Environmental Law Clinic at Tulane University submitted a notice of intent to sue Venture Global for violations of the Clean Air Act at its existing Calcasieu Pass facility.

The Bucket Brigade, an environmental group based in New Orleans, previously noted more than 2,000 instances where emissions from the facility exceeded allowable limits during the facility’s first year of operation. The environmental groups haven’t yet filed their lawsuit; however, the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality has since sent Venture Global a notice of potential penalties for its emissions.

For Ray Mallett and the other fishermen, any relief from additional LNG development on the Calcasieu River can’t come soon enough. When the inshore shrimp season opened on August 11, Mallett loaded his boat, Cajun Memories, with several days’ worth of supplies and headed east toward Vermilion Bay, a twelve-and-a-half-hour journey, in search of shrimp.

“I couldn’t make any money here,” Mallet said. “I had to go elsewhere.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,