Early this year Colombia was lauded by NGOs and journalists around the world for protecting its forests. Deforestation had dropped precipitously and it seemed that President Gustavo Petro had delivered on his commitment to make Colombia a “world power in life.”

But these hopes were punctured at a press conference in early April when environment minister Susana Muhamad González announced there had been a historic spike in deforestation in the last months of 2023 and the start of 2024.

Muhamad blamed armed groups—participants in Colombia’s decades-old internal conflict—saying that “nature has been put in the middle of the conflict.” The dissidents are accused of using deforestation as leverage in ongoing peace negotiations with the Colombian government.

We’re hiring!

Please take a look at the new openings in our newsroom.

See jobs

“This is a violation of international law,” said Muhamad, “damage to the environment is prohibited in as a form of warfare.”

Conflict and the environment have a long and complicated relationship in Colombia.

For decades, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the biggest left-wing guerilla group in Latin America, had protected the forests, on the whole. “They created rules for local communities and outsiders on what could be done, what forests could be knocked down and what couldn’t,” said Kyle Johnson, founder of CORE, a Colombian research group on conflict.

This unlikely environmentalism had a simple logic: “Tree cover was important for FARC to protect them from being bombed, and they were being bombed a lot,” said Johnson. Through their controls, the group became a de-facto environmental authority in an area of the country where the state had little to no presence.

This lasted throughout the 2000s until 2016, when Colombia signed a historic deal with the FARC.

As part of the peace agreement the government promised land reform and rural development. What came instead was a power vacuum. FARC withdrew from huge areas of the country that they had controlled, and the state did not step in to fill the gap.

As the guerilla group demobilized, deforestation jumped 44 percent, particularly in the areas that had been under their control. Muhamad, at that time an environmental activist, described it in 2016 as a ‘land rush’ in which criminal groups and cattle ranchers moved to occupy land that lacked proper titling and enforcement by the state.

Though the main part of FARC agreed to demobilize and put down their weapons, some factions of the group refused to sign the deal and stayed behind in Meta, Guaviare and Caqueta, the state-like regions known as departments that form the northern frontier of the Colombian Amazon. These dissidents are known as FARC EMC (Estado Mayor Central).

Recently deforested land in Caqueta, Colombia.

EMC broke from the previous practices of FARC and allowed deforestation in the areas under its control. This was partly a financial decision to fund their operations, as farmers both small and large pay the armed groups per hectare of land cleared as a form of tax.

With the election of Petro in 2022, things changed again. Alongside his ambitions to end deforestation, he campaigned under a slogan of “total peace” and committed to build on the deal signed with FARC in 2016, and include the remaining dissident groups still at war with the state.

Preserving forests was a part of the talks from the very start. “It was privately, explicitly, quid pro quo,” said Johnson. “We know that the government asked the EMC to prohibit deforestation from very early on in the process.”

Initially this joint pitch on peace and environment delivered results.

Deforestation dropped by 29 percent in the first year of Petro’s presidency. The EMC created new rules for communities that lived under their control that explicitly forbid deforestation. “The decrease in deforestation in 2023 is because of the EMC,” Johnson emphasizes, “not because of any big government programs or strategy.”

But at the start of this year, as negotiations between the government and the EMC were becoming more difficult, the armed group realized they had leverage over a government that had been very public on the importance of their environmental agenda. EMC changed policy and allowed farmers to clear large areas of forest and, in some cases, even ordered it.

“They saw the influence they could have on deforestation and decided to demonstrate this power to the government,” said a source who asked to remain anonymous because he is implementing environmental projects in an area under EMC control. “They wanted to show they can choose when to turn on and off the tap.”

The armed groups use deforestation not only as a tactic to influence the peace talks, the source said, but “they also use this as a form of control over these territories, over the communities that live there, to exercise their power.”

Challenges on the Ground in Caqueta

Caqueta, a department in the Colombian Amazon, is the region worst affected by this recent spike in tree loss, enduring almost a third of the nation’s deforestation in the last quarter of 2023. A region almost as big as Portugal, it holds a remarkable and biodiverse range of ecosystems, from the high Andes to lowland Amazon. For a long time Caqeuta has also been one the regions most affected by Colombia’s conflict with the guerillas.

Karina Monroy is the technical director of the ‘Mesa Forestal’ in Caqueta, a group that brings together government, cattle ranchers, NGOs and communities to talk about deforestation and try to bring it under control. It’s a difficult job.

Monroy knows more than most about the ups and downs of Colombia’s conflict and the country’s battle with deforestation. Her father, a community leader, was murdered just a month before the 2016 peace deal was signed. They still don’t know whether he was killed by the guerillas, or groups connected with the state.

“In the south you have illegal economies—coca being grown to produce cocaine, closer to Putamayo,” she said. “Toward the north the forests are cleared for cattle ranching. This has been the biggest issue recently.”

While cows might fill the freshly cleared lands, they are often part of an illegal process of land grabbing, used to establish and legitimize ownership of newly deforested lands. So, although the trees may be cut down by small local farmers, there are often bigger financial interests at play.

The uptick in violence has also made it harder for Monroy and the NGOs she works with to implement projects that could help to reduce deforestation. This year, the armed groups have stopped international NGOs from visiting the region where they have projects with local communities, she said.

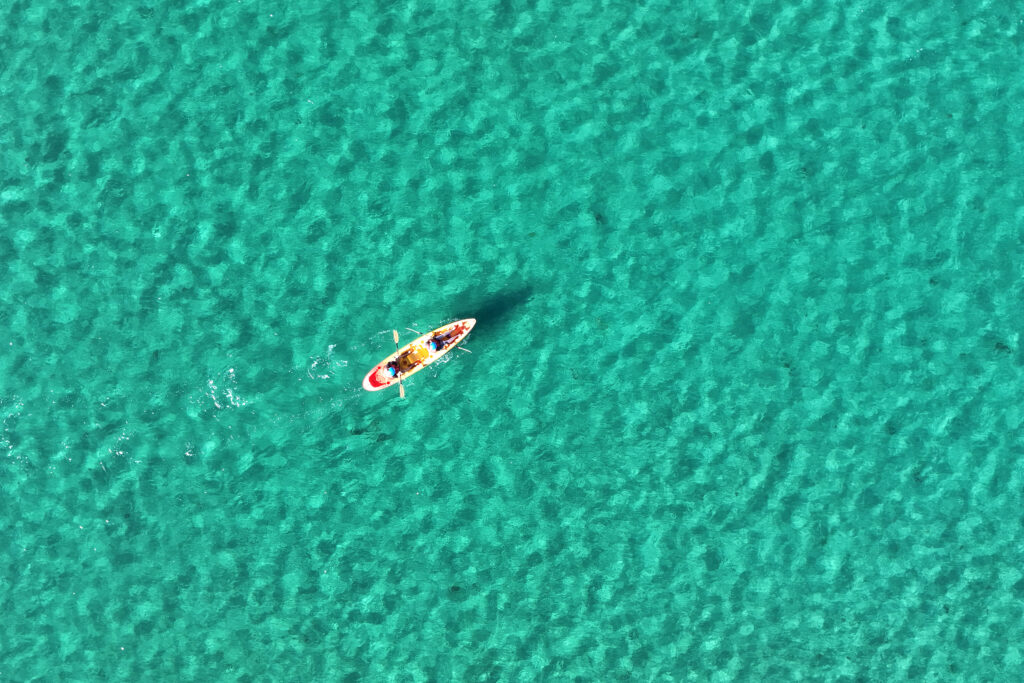

Ecotourism has long been touted as a potential solution to both deforestation and the poverty that underpins the conflict in Colombia. But in Caqueta, it has been difficult to get such businesses off the ground.

In other parts of Colombia, conservation, peace and tourism has been shown to work. In the Serranía de la Macarena, a national park, former guerillas now take tourists white water rafting in a project funded by international donors like the governments of Norway and the United Kingdom.

Jorge Munoz is a doctor in Florencia, the regional capital of Caqueta, who runs a sustainable tourism business in his spare time.

In the emergency room he’s seen the casualties of the conflict. During the height of the conflict, a helicopter would arrive every few weeks with injured soldiers, dissidents or just local farmers caught up in the fighting. People close to him were kidnapped and he was threatened by the rebels.

But Munoz’s real passion is bird watching. Of the more than one thousand birds documented in Caqueta, he reckons to have seen almost ninety percent of them.

After the 2016 peace deal, optimistic about the future and recognizing the potential for bird watching in the area, he started a tour company to guide birders visiting from around the world.

“With the peace process, many areas were opening up for the first time, areas that I had not been able to visit,” Munoz said. They had tourists from across Europe and the U.S. eager to see an area that for so long had been closed off. “This was a hopeful time,” he said.

In recent years, however, the situation had deteriorated, Munoz said. “In the last three years we’ve seen safety decline in some of the areas we visit, and last year even more,” he said. “The communities we work with warn us not to visit them.”

Munoz pointed out the paradox the business faces. More visitors to the region could help protect the forest, “but for nature tourism to reach a scale that would be meaningful for our economy, we have to guarantee the security of the region,” he said.

The chief of the tourist police in Florencia emphasized the importance of visitors taking precautions. “Tourists are safe to come to Caqueta,” he said, but “you have to travel with a guide from the community, who can talk to the armed groups, so they know you’re coming and why you’re going to the area.” I asked an officer whether that meant he and his colleagues were also talking to the armed groups, his answer was emphatic. “No. They’re our enemies.”

Where Next for Colombia

These recent challenges come at a difficult time for Colombia’s climate ambitions. Petro is due to host the U.N. Biodiversity talks in December in the city of Cali. But what would have been a chance to showcase their success is now more complicated.

Yet, the government may have a brief reprieve in coming months. Until recently Colombia has been suffering from droughts due to the El Niño weather pattern. The lack of rains contributed to deforestation because slash and burn agricultural practices are easier when the countryside is dry. But IDEAM, Colombia’s meteorological institute, announced in early May that the country is now in the process of transitioning to La Niña, which means heavier rainfall and most likely a lower rate of deforestation—at least until the next dry season in November.

Petro’s commitment to total peace could also be shifting. He recently announced increased military operations in the southwest of the country against a separate faction of EMC that is not taking part in the peace negotiations, after a spike in violence that has seen car bombings and the deaths of Indigenous leaders, children and soldiers in recent months.

Muhamad says that the government will not leave communities behind ”We will not abandon these areas, or local leaders,” she said. “We will support the communities and I want to tell them that they count on the government.”

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

Whether Colombia’s new crackdown on the guerillas will extend to deforestation by armed groups remains to be seen.

Monroy from the Mesa Forestal in Caqueta still holds on to a belief that at some point, Colombia will find a way through.”‘I’m always hopeful,” she said. “I’m one of those people who say that after the storm there will be calm. But I just don’t know how long this storm will last.”