GONZALES, Texas—More than 500 enormous oil tanks dot the floodplains of the Guadalupe River and its tributaries where they cross one of Texas’ leading oilfields, an Inside Climate News investigation has found, posing risk of an environmental disaster.

Longtime residents of these historic ranchlands still remember the last time these plains filled up with water in a biblical inundation in 1998. That was before the fracking boom hit this region and the oil-rich geological formation that lies beneath it, known as the Eagle Ford Shale.

Today, a repeat of the historic flood could wreak havoc, locals worry.

“There’s a whole lot of tanks full of oil that are going to float away,” said Sara Dubose, a fifth-generation landowner in Gonzales County with 10 tanks in the floodplain on her family’s ranchlands, each holding up to 21,000 gallons of oil or toxic wastewater. “Spill all over our land and ruin it for 100 years.”

Almost 20 feet of water could submerge some of the tanks on the Dubose family’s land in an event similar to 1998, according to an Inside Climate News analysis of data from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

Inside Climate News scoured satellite imagery on Google Maps to identify batteries of oil tanks and other oilfield infrastructure near waterways of the Guadalupe River Basin where it crosses the Eagle Ford Shale. We then took the latitude and longitude coordinates of each tank battery and used FEMA’s flood mapping data to extract the agency’s estimates for the depths of its benchmark flood scenarios at these locations.

In some areas, the 1998 flood exceeded the worst-case scenario considered by disaster planners. FEMA calls this the “500-year flood,” a hypothetical event the agency estimates has a 0.2 percent chance of happening in any year.

Today, a 500-year flood across this entire area would cover at least 22 tank batteries containing 144 individual oil and wastewater tanks with 10 or more feet of water, ICN’s analysis found. Of those, 12 tanks would sit beneath at least 20 feet of water.

FEMA’s estimates for a 500-year flood understate present risk in many locations, research shows, as warming air and oceans continue to fuel an intensification of extreme rainfall.

Dubose experienced the 1998 flood, when the Guadalupe River sprang from its banks and filled the shallow valleys here at the edge of the coastal plains. The water almost reached her house, seven miles from the river, where it trapped her for a week, covering Highway 183 in both directions as it drained slowly into San Antonio Bay on the coast.

In a warming world with more intense rainfall, a future flood could be even more severe.

“One day, it’s going to happen,” Dubose said. “We’ve all been concerned about the oilfield flooding.”

Flood-Threatened Tank Batteries in the Eagle Ford Shale

When flooding hit a smaller oilfield in northeastern Colorado in 2013, authorities tallied two dozen overturned tanks and almost 90,000 gallons of oil and wastewater spilled. During Hurricane Katrina in 2005, millions of gallons of oil spilled when several supersized storage tanks floated off their pads. In 1994, flooding on the San Jacinto River in East Texas severed eight pipelines, ignited massive fires, injured hundreds of people and released more than 2 million gallons of petroleum products.

Last summer, severe flooding in the Texas Hill Country near Kerrville washed away a girls’ summer camp and killed more than 100 people along the Guadalupe River, 150 miles upstream from the Eagle Ford Shale.

The rules for building in floodplains in Texas fall to county governments, often small and rural. The 78 tank batteries in the Guadalupe floodplains identified by Inside Climate News through satellite imagery all sit within Gonzales and DeWitt counties, which have a combined population of around 40,000 people.

It was left to the governments of these two counties to design and implement floodplain policies during the shale oil boom.

“Those are not issues that most counties, on an individual basis, are well suited to handle,” said Todd Votteler, former executive manager of science, intergovernmental relations and policy at the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority. “It raises a question of how serious the state is about avoiding future flood damage in high-risk areas if we don’t have a statewide policy.”

Tank batteries at well sites aren’t typically secured to the ground by anything but the weight of the oil and wastewater inside them. While they are especially vulnerable, they aren’t the only industry infrastructure that could be affected by flooding. Eight oil pipelines and about two dozen gas pipelines cross the Guadalupe River in the Eagle Ford Shale, and others cross local creeks.

The batteries in the floodplain on Dubose’s property were previously operated by Canadian firm Baytex Energy, which sold all of its Eagle Ford Shale assets in November for $3.2 billion to an undisclosed buyer. Other operators with numerous batteries in the floodplains include EOG Resources, Devon Energy and Burlington Resources, a subsidiary of ConocoPhillips. None of the companies responded to requests for comment.

These floodplains also contain many open and buried pits of drilling waste. Dubose unsuccessfully sued an oil company in 2018, alleging that the unlined pit where it buried drilling mud and wastewater on her property was responsible for the orange, gassy goo that seeped up from the earth during heavy rainfall.

“Think about all the stuff that’s soaked into the ground,” said Blake Muir, a fifth-generation landowner with more than a dozen wells on his property. “They’ve got thousands of chemicals that go into the drilling mud.”

The Flood of 1998

Muir’s land has been in his family since the 1840s. Outside his old, single-story ranch house near the border of Gonzales and DeWitt counties, a private airplane hangar and a waterpark-style swimming pool commemorate the riches that fracking brought to this region.

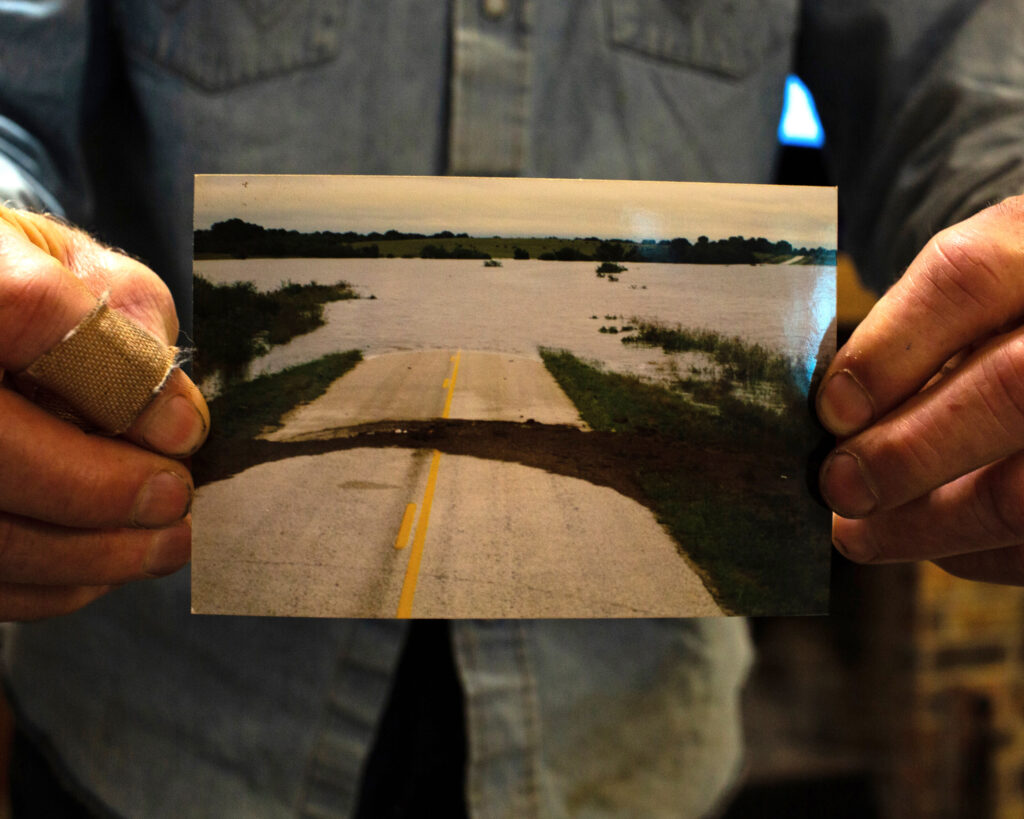

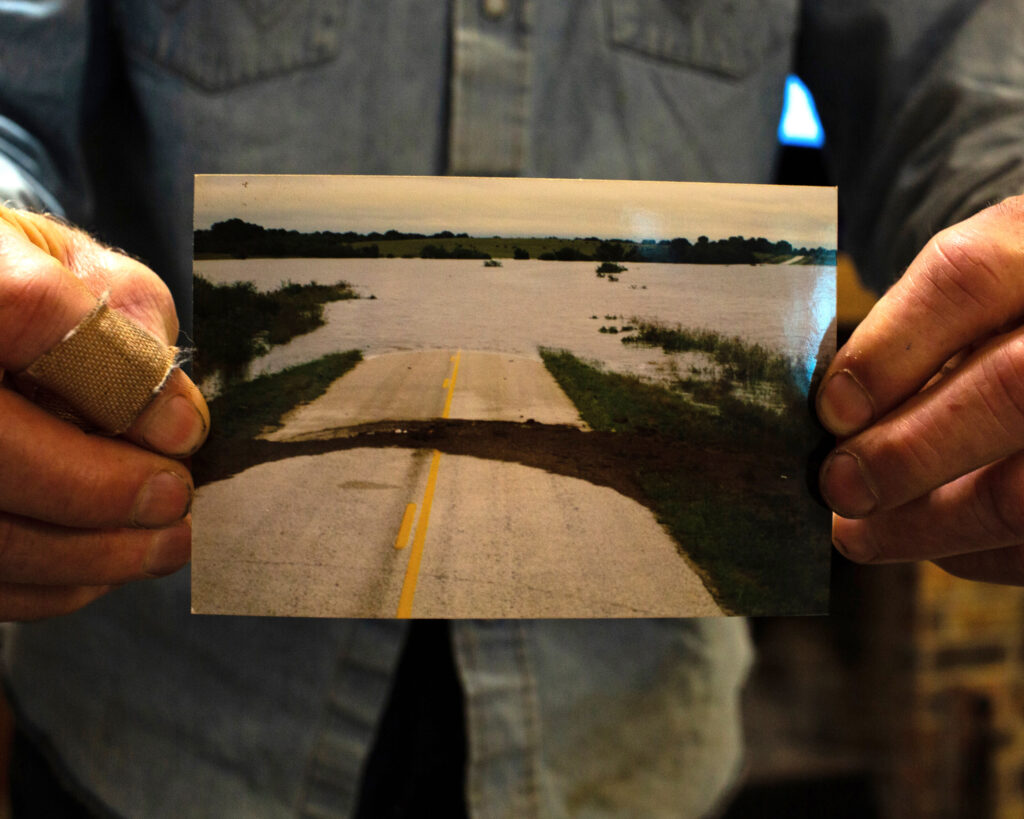

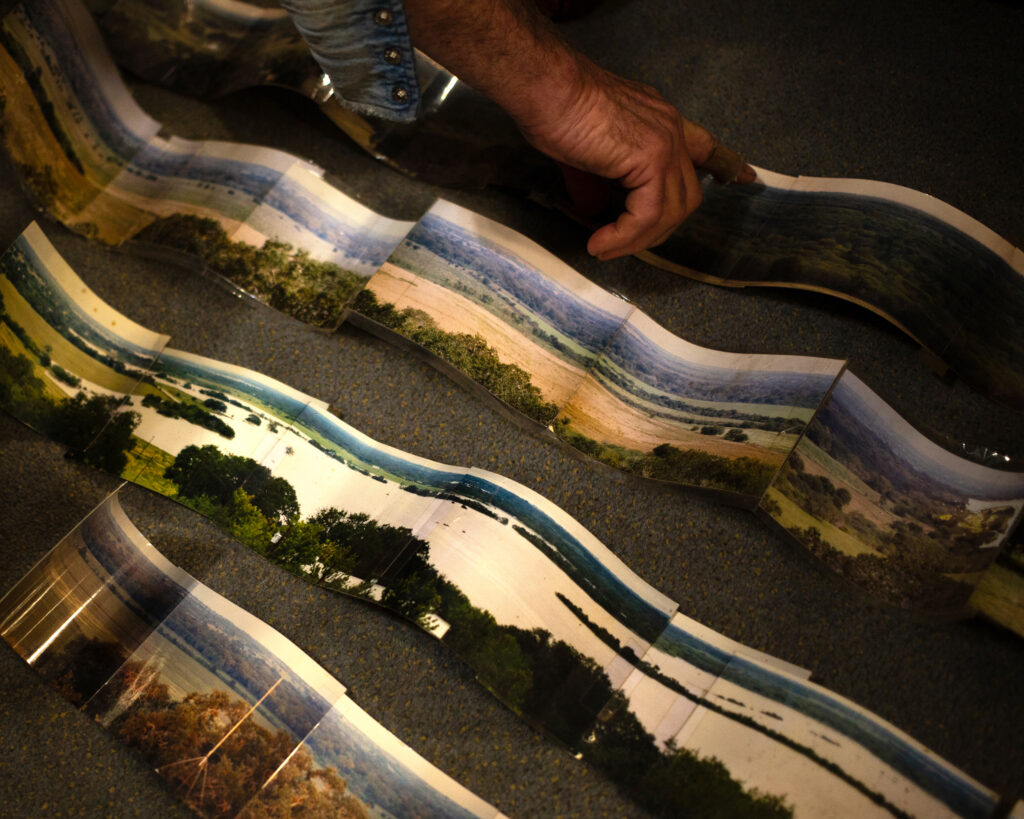

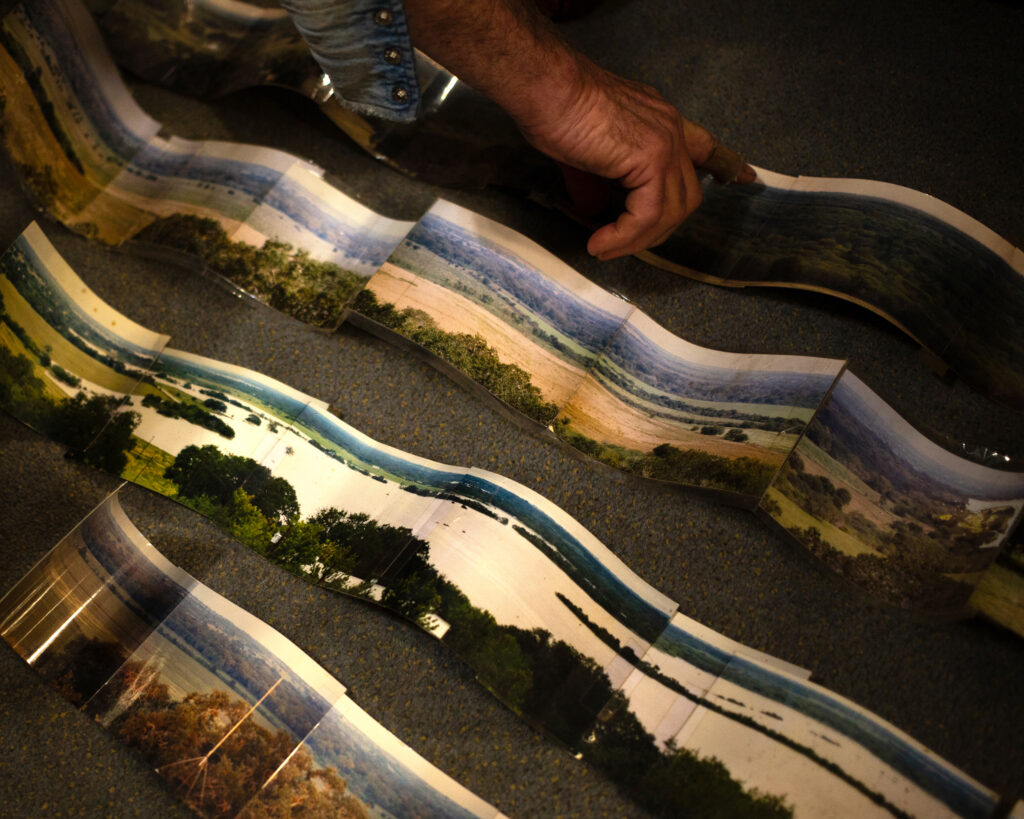

Inside the house, between clamoring dogs, Muir sifted through boxes of photos that predated the shale boom. He pulled out strips of 11 film photos taped together to show the vast landscape of water that overtook this rolling savannah on the morning of Oct. 17, 1998.

It rose far past the tops of the trees. It even covered a spot on Muir’s land where a tank battery now stands, 1.5 miles from the Guadalupe River.

“I thought the whole world was going to flood,” he said as he flipped through old pictures. “We haven’t had a flood like that since the oilfield hit us.”

It all seemed to happen in minutes, recalled Ben Prause, a former elected executive of DeWitt County who presided during the flood. The water wasn’t even raging but almost calm as it swiftly rose up to swallow about two thirds of the town of Cuero. In one case, he said, sheriff’s deputies entered a home with water at their knees to save an old woman, then walked out minutes later with water at their chests.

“It was so rapid,” said Prause, 92, at his home in downtown Cuero, a few blocks from the 1998 waterline. “It was just terrible. Water was everywhere.”

It wasn’t just the Guadalupe River, he said. Several major tributaries also flooded to make the situation worse. Torrential rains hit the upper reaches of Plum Creek and Sandies Creek, which both gushed simultaneously into the Guadalupe.

“What made it so bad is they all hit about the same time,” Prause said.

These creeks barely trickle for most of the year, said Prause, a 1950 graduate of Cuero High School, but on rare occasions their large floodplains fill.

In 1998 the floodwaters south of Gonzales were several miles wide, said a report issued the next year by the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority and FEMA, exceeding predicted worst-case scenarios in some areas.

“It was the flood that many thought would never happen,” the report said. “Unfortunately, an even greater flood will occur sometime in the future.”

The Fracking Boom

The 1998 flood caused a few oil spills, said James Dodson, 71, co-founder of the San Antonio Bay Partnership and the son of a south Texas pipeline technician. His late wife worked for Texas’ environmental regulator and spent weeks overseeing cleanups. But the extent of oilfield infrastructure at that time was nothing compared with today.

“That was long before the Eagle Ford Shale plays came along,” he said. “The landscape was so much different in that regard—there’s so many more facilities and well pads now.”

Today, along one eastward turn in the Guadalupe’s snaking course, three batteries consisting of 15 tanks would sit under about 20 feet of water in a 500-year flood. One of them, operated by EOG Resources, sits just 500 feet from the riverbank.

Two miles from the Guadalupe River, four tanks operated by Burlington Resources would take on almost 23 feet of water.

Near Boggy Creek, east of the Guadalupe River by the small town of Dreyer, 10 feet of water would cover EOG Resources’ Shiner Hub gas processing plant, a complex of 14 tanks, pipes, motors, chemical separators and flares.

Along Peach Creek, southeast of Gonzales, batteries of 12 and 28 tanks previously operated by Baytex Energy would sit under 13 and 8 feet of water, respectively.

The oil from toppled tanks probably wouldn’t spill onto the land around them, said Dodson, a former water department director for the city of Corpus Christi who worked South Texas oilfields in the 1970s. Instead, he predicted, it would float on the water and end up at the edge of the flood’s crest, like the rings in a bathtub. More of it, he said, would wash over the creeks and estuaries of San Antonio Bay then into the Gulf of Mexico.

“It’s a disaster waiting to happen,” said Sister Elizabeth Riebschlager, an 89-year-old Catholic nun from Cuero. “They have these oil wells all through these areas that flooded like it’s no problem.”

The oilfield infrastructure here dates back less than 20 years to the shale revolution, when innovations in horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing unleashed an explosion of new oil exploration.

Back then, Riebschlager, the daughter of a local civic leader, held town hall meetings for local families who were baffled by the swarm of businessmen and lawyers descending on their sleepy countryside, whipping up 100-page contracts and casually writing checks for mind-boggling sums.

Many landowners warned the oil companies about flooding, she said.

Riebschlager related the story of one rancher: “When they were getting ready to drill there, he said, ‘Please don’t drill them here, it’s a floodplain. They will flood.’ The oil man says, ‘Don’t worry, we’ll have all the oil and gas out of this ground before the next flood.”

Dubose, who missed out on the riches of the oil boom because her mother sold her family’s mineral rights, got a similar answer when she mentioned 1998 to the company drilling on her land. She recalls a man telling her: “That was a 100-year flood so it won’t happen for another 100 years.”

Misunderstanding the Risk

That’s a common misconception surrounding terms like the 100-year and the 500-year flood, said Matthew Berg, CEO of Houston-based water risk management firm Simfero. A former water specialist with Texas A&M AgriLife, he understands why the general public is misled.

“They would understand a 100-year flood only happens once every 100 years,” he said. “That’s a problem because statistics don’t work that way.”

They don’t literally return only once every century. Rather, computer models estimate that such an event has a 1 percent chance of occurring at any given spot in a year. What happened in previous years doesn’t change those odds.

Furthermore, Berg said, these estimated probabilities are “to some extent meaningless” where records go back barely 100 years. They are meant for purposes of development planning, not weather forecasting. We don’t really know the likelihood of storms across centuries, or when the 500-year floodplain of the Guadalupe River may fill up again. Two things are certain: It will fill again, and the chances are rising.

The warming climate is making precipitation more intense in Texas and beyond. A similar amount of rain falls in fewer, more concentrated storms than it used to, according to a 2024 report from the Office of the Texas State Climatologist at Texas A&M University.

“Many studies have documented an increase in extreme rainfall in Texas and surrounding areas,” the report said. “Extreme rainfall is strongly affected by increased temperatures.”

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

In Texas, as elsewhere on the planet, all 10 of the warmest years on record have occurred since 2011. Warming results from the accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, released in large part by burning fossil fuels like the oil in the tanks in the floodplains in the Eagle Ford Shale. And warmer air can hold more water vapor, leading to heavier downpours.

If global fossil fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emissions continue to climb, so will extreme rainfall.

“Extreme precipitation is expected to increase in intensity on average statewide,” said the state climatologist’s report. “We anticipate an additional increase of about 10% in expected extreme rainfall intensity in 2036 compared to 2001-2020 and an overall increase of over 20% compared to 1950-1999.”

These changes in rainfall intensity correspond to a 50 percent increase in the likelihood of extreme precipitation compared to 2001-2020, the report said, and a 100 percent increase compared to 1950-1999.

However, heavy rains alone don’t always make a mega-flood. They have to fall on just the right areas, across multiple tributaries of a single river so that their waters all converge at once downstream.

A Close Call Last Year

If a 500-year flood returns to the Eagle Ford Shale, it’s hard to tell how much oil, wastewater and other petroleum fluids could spill. Conventional oilfield tanks range from 210 to 750 barrels in size, about 13,000 to 32,000 gallons. Typical tank batteries in the Eagle Ford Shale often include five 500-barrel oil tanks and one 500-barrel wastewater tank, according to an investor presentation by Baytex Energy. Some are out of use or empty, some are full, most are in between.

Whatever fluids wash down the river would flow into San Antonio Bay, part of the winter grounds for the world’s last flock of wild, endangered whooping cranes, then into the Gulf of Mexico.

“With a flood it causes a lot more dispersion. It breaks it up then you’ve got oil mixed with sediment and debris. It can stink and it’s much, much harder to clean up,” said Diane Wilson, founder of San Antonio Bay Estuarine Waterkeeper and a 77-year-old former shrimper who lives near the mouth of the Guadalupe River. “It would be unbelievable, the damage it could do.”

Last summer, Dubose thought it was about to happen. As soon as she saw the news, late at night on the Fourth of July, she rushed out and sped her white Hummer down ranch roads to the river.

Incredible rainfall was hitting the Guadalupe about 150 miles upstream in the Hill Country near Kerrville. Online posts said the water had washed away a summer camp for girls.

Dubose had flashbacks to 1998, when there were also overnight rainstorms, far upriver, that put this region underwater for a week. So she hurried to save a mobile home parked at her fishing camp by the river, the same spot where she’d lost a mobile home in 1998.

Almost there, she passed nervously between the towering, three-story tank batteries in the floodplain on her land, then past the site of the buried waste where, she said, the grass dies each time heavy rains bring the water table to the surface.

Luckily for Dubose, no torrent came downriver. For Kerrville, in the Hill Country, it was the worst flood since 1987. But all the heavy rain fell upstream of a major dam and reservoir, where water levels were low enough to absorb it. So the Eagle Ford Shale was spared, for now.

“What happened in Kerrville, if that happens here, that’s a really bad situation,” Dubose said. “We’ve told the oilfield, this is going to flood someday.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,