A Norwegian battery company has been working since 2022 to open a supersize factory outside of Atlanta that will bring more than 700 jobs to the region.

Freyr Battery is developing a manufacturing process for lithium-ion batteries that it says will be less expensive and have less waste than the processes many competitors use. The batteries would be available for stationary energy storage and for use in large electric vehicles such as buses.

The Georgia plant is one of the many projects whose existence is at least in part due to the Inflation Reduction Act, President Joe Biden’s 2022 climate law.

But Freyr has hit some potholes on its way to the Peach State.

We’re hiring!

Please take a look at the new openings in our newsroom.

See jobs

The company said in November that it would not meet a target for one of its technical milestones by the end of 2023, and it was delaying the opening of a large-scale plant in Norway. One upshot was that the plant in Coweta County, already in the works about 40 miles southwest of Atlanta with a projected opening of 2026, would go online before the one in Norway.

Investors reacted negatively and the company’s share price dropped by about half.

This all occurred in Birger Steen’s first few months as Freyr’s CEO. The company board appointed him to the role in August, and said the previous CEO, co-founder Tom Einar Jensen, would become executive chairman. Steen has about 30 years of experience in the technology sector, including stints leading Microsoft’s operations in Norway and Russia.

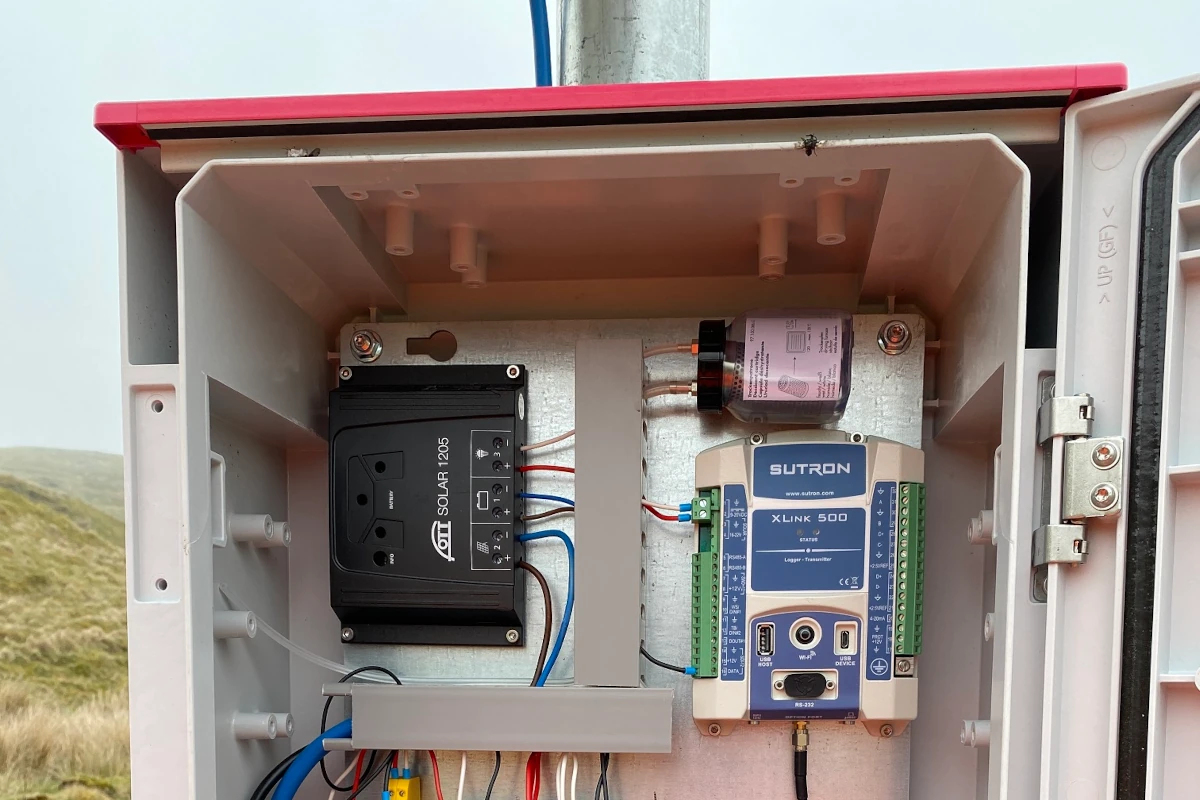

He now faces some major challenges. The main one is taking place at the company’s technology and development center in Mo i Rana, a small city in northern Norway, where employees are taking a lithium-ion battery technology developed at MIT and trying to make it work in an automated manufacturing system.

The development of the manufacturing process is teeing up the opening of the plant near Atlanta, a complex that will cost more than $2.5 billion to build and employ 723 people. (Right now, the company has a head count of 213, most of them in Norway.)

The project would benefit from the 45X Advanced Manufacturing Production Credit in the IRA, which is paid out based on the capacity, in megawatt-hours, of batteries made at the plant. The credit is much better than anything Norway can offer to Freyr, which is a disappointment to leaders in Norway, as the New York Times reports this week, but a boon to the United States.

I spoke with Steen in a video call. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

How would you describe the company to someone who’s not familiar with it?

We’re here to decarbonize transportation systems and storage systems by making the world’s most sustainable battery. That’s what we do.

The thing that inspires us quite a lot these days is the opportunity to help build a critical component of the future energy system, and ability to produce that in the west, because 95 percent of LFP [lithium iron phosphate, a type of lithium-ion battery] production capacity right now is in China. We think it’s great that they’ve taken a lead and shown that it’s possible to build giga-scale battery production at an affordable cost, but we have to learn to do that too. That capability has to be on all continents, and in all regions. And certainly that should be in America, and it should be in Europe.

You had some recent news about a production milestone in your facility in Norway. What happened there and why is it important?

What we did this week was successfully conduct automated casting trials of electrodes with active electrolyte slurry. Full automation is a precondition for getting to multiple gigawatt-hour scale, so that’s why it was important.

When you’re approaching a milestone like this, is there doubt? Do you go into that day thinking, “We don’t know if this is going to work today?” Or do you go into it thinking, “There’s a 90-plus percent chance this is all going to come together today?”

The interesting thing about serial number one, which is what this piece of production machinery is, is that there’s a relatively high variance in terms of your ability to hit your predicted timeline. So I’ll take an example from a little while ago, where we recently did the first semi-automatic casting of electrodes. We sort of had it scoped out to take potentially as much as 30 days to sort of tune it in to get it the appropriate accuracy and alignment. It took us 30 hours. So that’s a good day at work.

Then, the day after, we felt this was going to be really simple. We were going to start the automation process and there was this web we were casting on. It sits between two pallets. And then the two pallets squeeze together and the web is supposed to bend down so that you can cast a continuous stripe of slurry over these pallets. Trouble is it wasn’t bending down, it was bending up. And even when it was bending down after we increased the air pressure and the vacuum, it was wrinkling at the edges, and that’s no good because then you get a lack of homogeneity in the process. That was supposed to take 30 hours. It took 30 days. So when you hit a milestone, as per plan, you’re typically quite satisfied with it.

Why build a big plant in Georgia?

Our original plan was to build a big plant in Norway, because we have 100 percent green energy, hydropower and the prospect of local material supply with lithium and graphite and others. Very good location, close to a deepwater quay and good rail and road transport and great support from the community. And then we were also planning to build a facility in Georgia which was the result of a selection process. The reason we prioritized Georgia over other stateside locations was many of the same factors: very central, great airport close by, railroads, access to the port facilities, either by road or by rail, great partnership with local community, great welcome, a strong base of resources, local skills everywhere from sort of trade school level all the way up to the postdoc level.

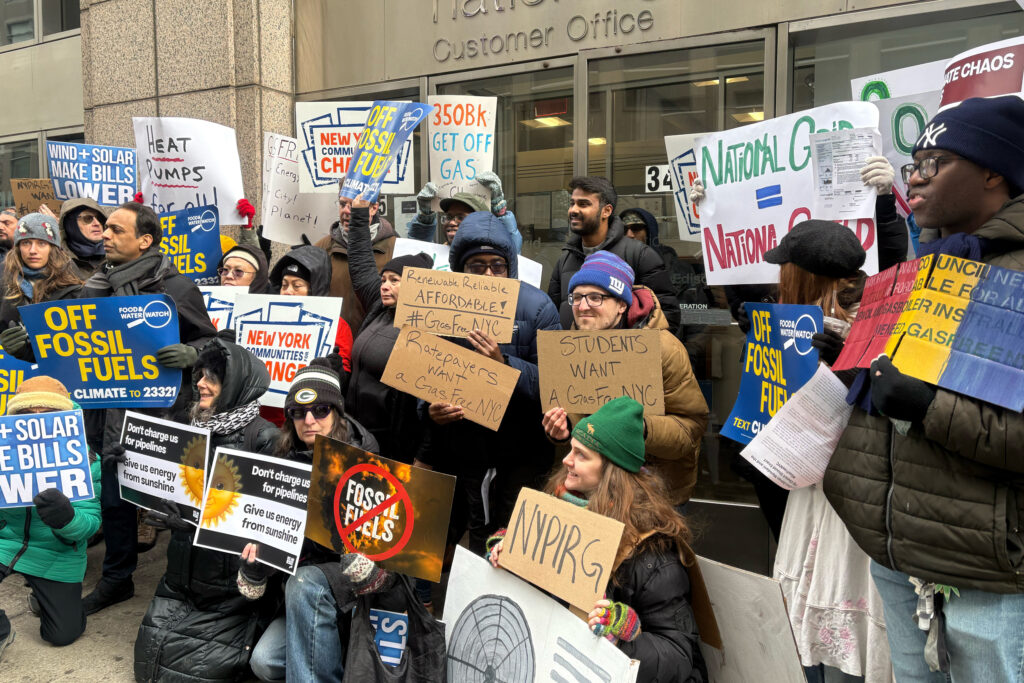

Our plan was originally to build in Norway first and then Georgia second. And then August, year before last, the IRA was passed into law. That was a real shock to the system. We took some time to digest and to understand whether there would be a relevant policy response happening from either European or local, national authorities and Norway. When we concluded that there wouldn’t be, it was a very easy choice, frankly, because project level funding or entity level funding for this kind of project is a fairly globalized capital market. The ability to fund it is going to flow to where the best economics are.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

One of the recurring themes within the U.S. is that it’s not widely understood by the public how the Inflation Reduction Act has helped to attract jobs and has helped to attract investment. From your vantage point, as a company that could locate anywhere, how big a difference does the IRA make?

Massive. Most programs, up until the IRA, they’ve tried to do something with the cost of capital or with development funding, or perhaps cheap land or things like that. They sort of give you committed benefits that happen principally at the beginning of a project or even before you put shovels in the ground. That’s sort of the path that Europe is still on when it comes to these kinds of these kinds of policy initiatives. The brilliance of the IRA is that it doesn’t have to pick winners the way the traditional approaches have to. With the IRA, you wait until you’re producing and you get support exactly to the tune that you produce volume. That’s very clever because if you show you’re already producing gigawatt hours of batteries, you’ve shown you’re a winner. The government doesn’t have to pick winners, but the market picks their own winners.

Lithium prices are really low right now. I am curious what that means for the economics of someone who produces batteries.

Cheap lithium means that the product becomes more affordable. And so the total addressable market expands as demand picks up for the product, which is a good thing.

Other stories about the energy transition to take note of this week:

Seven Automakers Join to Create Ionna, a Massive New U.S. EV Charging Network: A group of seven automakers (BMW, General Motors, Honda, Hyundai, Kia, Mercedes, and Stellantis) said they are joining forces to support Ionna, an EV charging network based on one that has been successful in Europe. The companies, which indicated last summer that they were working on something like this, said Ionna will have 30,000 locations by the end of the decade and some of them would have amenities that resemble airline lounges, as John Voelcker reports for Car and Driver. The CEO of the new venture is Seth Cutler, who has experience at two charging networks, EVgo and Electrify America. As I wrote last week, a lack of charging infrastructure is a major impediment to the growth of EV ownership, so the existence of Ionna is a good sign if the company can come anywhere close to meeting its goals.

The Biden Administration Plans a Major Carbon-Free Electricity Buy: The General Service Administration and Department of Defense are looking for options for obtaining 100 percent carbon-free electricity by 2030 at federal properties in 13 Midwest and Mid-Atlantic states. Such a procurement would be one of the federal government’s largest, as Andrew Freedman reports for Axios. The states cover the footprint of PJM Interconnection, the country’s largest grid region, which runs from New Jersey to Illinois and includes the government’s substantial holdings in the Washington, D.C., area.

Heat Pumps Outsold Gas Furnaces Again Last Year—and the Gap Is Growing: Heat pumps, which use electricity to heat homes and businesses, outsold gas furnaces last in 2023 for the second year in a row, as Alison F. Takemura reports for Canary Media. Americans bought 21 percent more heat pumps last year than the next most popular appliance, which was gas furnaces, according to a trade group. This is good for the climate and human health because it contributes to a reduction in the burning of natural gas.

EVs or Ethanol? Midwest Eyes Deep CO2 Cuts in Transportation: A push to reduce emissions from transportation is leading to questions about whether Midwestern states should embrace ethanol and carbon capture and storage, or should focus on a shift to electric vehicles, as Jeffrey Tomich reports for E&E News. Illinois, Michigan and Minnesota are all having versions of this discussion, with the farm lobby wanting to maintain a market for ethanol, most of which is derived from corn, and environmental advocates arguing that EVs are a better option if the goal is a rapid reduction in carbon emissions.

Correction: A previous version of this story stated that Birger Steen took over as CEO of Freyr in September 2023. He assumed that role in August.

Inside Clean Energy is ICN’s weekly bulletin of news and analysis about the energy transition. Send news tips and questions to [email protected].