As Earth’s annual average temperature pushes against the 1.5 degree Celsius limit beyond which climatologists expect the impacts of global warming to intensify, social scientists warn that humanity may be about to sleepwalk into a dangerous new era in human history. Research shows the increasing climate shocks could trigger more social unrest and authoritarian, nationalist backlashes.

Established by the 2015 Paris Agreement and affirmed by a 2018 report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the 1.5 degree mark has been a cliff edge that climate action has endeavored to avoid, but the latest analyses of global temperature data showed 2023 teetering on that red line.

One major dataset suggested that the threshold was already crossed in 2023, and most projections say 2024 will be even warmer. Current global climate policies have the world on a path to heat by about 2.7 degrees Celsius by 2100, which would threaten modern human civilization within the lifespan of children born today.

Paris negotiators were intentionally vague about the endeavor to limit warming to 1.5 degrees, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change put the goal in the context of 30-year global averages. Earlier this month, the Berkeley Earth annual climate report showed Earth’s average temperature in 2023 at 1.54 degrees Celsius above the 1850-1900 pre-industrial average, marking the first step past the target.

We’re hiring!

Please take a look at the new openings in our newsroom.

See jobs

But it’s barely registering with people who are being bombarded with inaccurate climate propaganda and distracted by the rising cost of living and regional wars, said Reinhard Steurer, a climate researcher at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna.

“The real danger is that there are so many other crises around us that there is no effort left for the climate crisis,” he said. “We will find all kinds of reasons not to put more effort into climate protection, because we are overburdened with other things like inflation and wars all around us.”

Steurer said he doesn’t expect any official announcement from major climate institutions until long after the 1.5 degree threshold is actually crossed, when some years will probably already be edging toward 2 degrees Celsius. “I think most scientists recognize that 1.5 is gone,” he said.

“We’ll be doing this for a very long time,” he added, “not accepting facts, pretending that we are doing a good job, pretending that it’s not going to be that bad.”

In retrospect, using the 1.5 degree temperature rise as the key metric of whether climate action was working may have been a bad idea, he said.

“It’s language nobody really understands, unfortunately, outside of science,” he said. ”You always have to explain that 1.5 means a climate we can adapt to and manage the consequences, 2 degrees of heating is really dangerous, and 3 means collapse of civilization.”

Absent any formal notification of breaching the 1.5 goal, he hopes more scientists talk publicly about worst-case outcomes.

“It would really make a difference if scientists talked more about societal collapse and how to prepare for that because it would signal, now it’s getting real,” he said. “It’s much more tangible than 1.5 degrees.”

Instead, recent public climate discourse was dominated by feel-good announcements about how COP28 kept the 1.5 goal alive, he added.

“This is classic performative politics,” he said. “If the fossil fuel industry can celebrate the outcome of the COP, that’s not a good sign.”

Like many social scientists, Steurer is worried that the increasingly severe climate shocks that warming greater than 1.5 degrees brings will reverberate politically as people reach for easy answers.

“That is usually denial, in particular when it comes to right-wing parties,” he said. “That’s the easiest answer you can find.”

“Global warming will be catastrophic sooner or later, but for now, denial works,” he said. “And that’s all that matters for the next election.”

‘Fear, Terror and Anxiety’

Social policy researcher Paul Hoggett, professor emeritus at the University of the West of England in Bristol, said the scientific roots of 1.5-degree target date back to research in the early 2000s that culminated in a University of Exeter climate conference at which scientists first spelled out the risks of triggering irreversible climate tipping points above that level of warming.

“I think it’s still seen very much as that key marker of where we move from something which is incremental, perhaps to something which ceases to be incremental,” he said. “But there’s a second reality, which is the reality of politics and policymaking.”

The first reality is “profoundly disturbing,” but in the political world, 1.5 is a symbolic maker, he said.

“It’s more rhetorical. it’s a narrative of 1.5,” he said, noting the disconnect of science and policy. “You almost just shrug your shoulders. As the first reality worsens, the political and cultural response becomes more perverse.”

A major announcement about breaching the 1.5 mark in today’s political and social climate could be met with extreme denial in a political climate marked by “a remorseless rise of authoritarian forms of nationalism,” he said. “Even an announcement from the Pope himself would be taken as just another sign of a global elite trying to pull the wool over our eyes.”

An increasing number of right-wing narratives simply see this as a set of lies, he added.

“I think this is a huge issue that is going to become more and more important in the coming years,” he said. “We’re going backwards to where we were 20 years ago, when there was a real attempt to portray climate science as misinformation,” he said. “More and more right wing commentators will portray what comes out of the IPCC, for example, as just a pack of lies.”

The IPCC’s reports represent a basic tenet of modernity—the idea that there is no problem for which a solution cannot be found, he said.

“Even an announcement from the Pope himself would be taken as just another sign of a global elite trying to pull the wool over our eyes.”

“However, over the last 100 years, this assumption has periodically been put to the test and has been found wanting,” Hoggett wrote in a 2023 paper. The climate crisis is one of those situations with no obvious solution, he wrote.

In a new book, Paradise Lost? The Climate Crisis and the Human Condition, Hoggett says the climate emergency is one of the big drivers of authoritarian nationalism, which plays on the terror and anxiety the crisis inspires.

“Those are crucial political and individual emotions,” he said. “And it’s those things that drive this non-rational refusal to see what’s in front of your eyes.”

“At times of such huge uncertainty, a veritable plague of toxic public feelings can be unleashed, which provide the effective underpinning for political movements such as populism, authoritarianism, and totalitarianism,” he said.

“When climate reality starts to get tough, you secure your borders, you secure your own sources of food and energy, and you keep out the rest of them. That’s the politics of the armed lifeboat.”

The Emotional Climate

“I don’t think people like facing things they can’t affect,” said psychotherapist Rebecca Weston, co-president of the Climate Psychology Alliance of North America. “And in trauma, people do everything that they possibly can to stop feeling what is unbearable to feel.”

That may be one reason why the imminent breaching of the 1.5 degree limit may not stir the public, she said.

“We protect ourselves from fear, we protect ourselves from deep grief on behalf of future generations and we protect ourselves from guilt and shame. And I think that the fossil fuel industry knows that,” she said. “We can be told something over and over and over again, but if we have an identity and a sense of ourselves tied up in something else, we will almost always refer to that, even if it’s at the cost of pretending that something that is true is not true.”

Such deep disavowal is part of an elaborate psychological system for coping with the unbearable. “It’s not something we can just snap our fingers and get ourselves out of,” she said.

People who point out the importance of the 1.5-degree warming limit are resented because they are intruding on peoples’ psychological safety, she said, and they become pariahs. “The way societies enforce this emotionally is really very striking,” she added.

But how people will react to passing the 1.5 target is hard to predict, Weston said.

“I do think it revolves around the question of agency and the question of meaning in one’s life,” she said. “And I think that’s competing with so many other things that are going on in the world at the same time, not coincidentally, like the political crises that are happening globally, the shift to the far right in Europe, the shift to the far right in the U.S. and the shift in Argentina.”

Those are not unrelated, she said, because a lack of agency produces a yearning for false, exclusionary solutions and authoritarianism.

“If there’s going to be something that keeps me up at night, it’s not the 1.5. It’s the political implications of that feeling of helplessness,” she said. “People will do an awful lot to avoid feeling helpless. That can mean they deny the problem in the first place. Or it could mean that they blame people who are easier targets, and there is plenty of that to witness happening in the world. Or it can be utter and total despair, and a turning inward and into a defeatist place.”

She said reaching the 1.5 limit will sharpen questions about addressing the problem politically and socially.

“I don’t think most people who are really tracking climate change believe it’s a question of technology or science,” she said. “The people who are in the know, know deeply that these are political and social and emotional questions. And my sense is that it will deepen a sense of cynicism and rage, and intensify the polarization.”

Unimpressed by Science

Watching the global temperature surging past the 1.5 degree mark without much reaction from the public reinforces the idea that the focus on the physical science of climate change in recent decades came at the expense of studying how people and communities will be affected and react to global warming, said sociologist and author Dana Fisher, a professor in the School of International Service at American University and director of its Center for Environment, Community, and Equity.

“It’s a fool’s errand to continue down that road right now,” she said. “It’s been an abysmal ratio of funds that are going to understand the social conflict that’s going to come from climate shocks, the climate migration and the ways that social processes will have to shift. None of that has been done.”

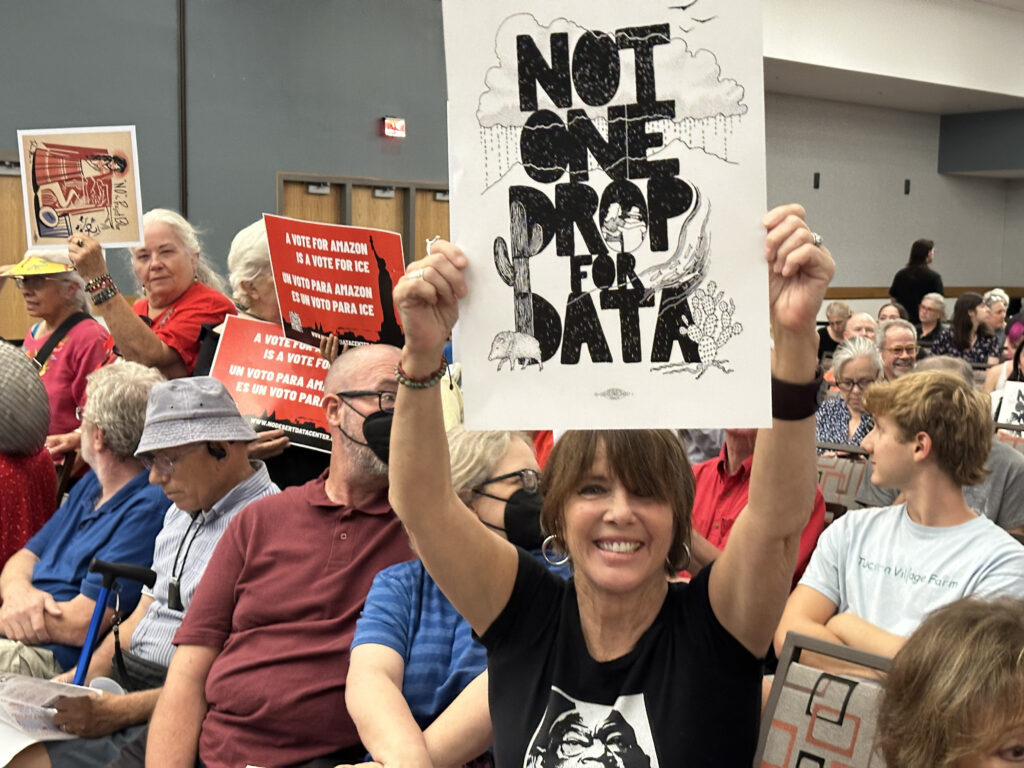

Passing the 1.5 degree threshold will “add fuel to the fire of the vanguard of the climate movement,” she said. “Groups that are calling for systemic change, that are railing against incremental policy making and against business as usual are going to be empowered by this information, and we’re going to see those people get more involved and be more confrontational.”

And based on the historical record, a rise in climate activism is likely to trigger a backlash, a dangerous chain reaction that she outlined in her new book, Saving Ourselves: From Climate Shocks to Climate Action.

“When you see a big cycle of activism growing, you get a rise in counter-movements, particularly as activism becomes more confrontational, even if it’s nonviolent, like we saw during the Civil Rights period,” she said. “And it will lead to clashes.”

Looking at the historic record, she said, shows that repressive crackdowns on civil disobedience is often where the violence starts. There are signs that pattern will repeat, with police raids and even pre-emptive arrests of climate activists in Germany, and similar repressive measures in the United Kingdom and other countries.

“I think that’s an important story to talk about, that people are going to push back against climate action just as much as they’re going to push for it,” she said. “There are those that are going to feel like they’re losing privileged access to resources and funding and subsidies.”

“When you see a big cycle of activism growing, you get a rise in counter-movements, particularly as activism becomes more confrontational, even if it’s nonviolent, like we saw during the Civil Rights period.”

A government dealing effectively with climate change would try to deal with that by making sure there were no clear winners and losers, she said, but the climate shocks that come with passing the 1.5 degree mark will worsen and intensify social tensions.

“There will be more places where you can’t go outside during certain times of the year because of either smoke from fires, or extreme heat, or flooding, or all the other things that we know are coming,” she said. “That’s just going to empower more people to get off their couches and become activists.”

‘A Life or Death Task For Humanity’

Public ignorance of the planet’s passing the 1.5 degree mark depends on “how long the powers-that-be can get away with throwing up smokescreens and pretending that they are doing something significant,” said famed climate researcher James Hansen, who recently co-authored a paper showing that warming is accelerating at a pace that will result in 2 degrees of warming within a couple of decades.

“As long as they can maintain the 1.5C fiction, they can claim that they are doing their job,” he said. “They will keep faking it as long as the scientific community lets them get away with it.”

But even once the realization of passing 1.5 is widespread, it might not change the social and political responses much, said Peter Kalmus, a climate scientist and activist in California.

“Not enough people care,” he said. “I’ve been a climate activist since 2006. I’ve tried so many things, I’ve had so many conversations, and I still don’t know what it will take for people to care. Maybe they never will.”

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

Hovering on the brink of this important climate threshold has left Kalmus feeling “deep frustration, sadness, helplessness, and anger,” he said. “I’ve been feeling that for a long time. Now, though, things feel even more surreal, as we go even deeper into this irreversible place, seeming not to care.”

“No one really knows for sure, but it may still be just physically possible for Earth to stay under 1.5C,” he said, “if humanity magically stopped burning fossil fuels today. But we can’t stop fossil fuels that fast even if everyone wanted to. People would die. The transition takes preparation.”

And there are a lot of people who just don’t want to make that transition, he said.

“We have a few people with inordinate power who actively want to continue expanding fossil fuels,” he said. “They are the main beneficiaries of extractive capitalism; billionaires, politicians, CEOs, lobbyists and bankers. And the few people who want to stop those powerful people haven’t figured out how to get enough power to do so.”

Kalmus said he was not a big fan of setting a global temperature threshold to begin with.

“For me it’s excruciatingly clear that every molecule of fossil fuel CO2 or methane humanity adds to the atmosphere makes irreversible global heating that much worse, like a planet-sized ratchet turning molecule by molecule,” he said. “I think the target framing lends itself to a cycle of procrastination and failure and target moving.”

Meanwhile, climate impacts will continue to worsen into the future, he said.

“There is no upper bound, until either we choose to end fossil fuels or until we simply aren’t organized enough anymore as a civilization to burn much fossil fuel,” he said. “I think it’s time for the movement to get even more radical. Stopping fossil-fueled global heating is a life-or-death task for humanity and the planet, just most people haven’t realized it yet.”