The Bay Area Air District kicked off the new year with a warning for residents of the nine counties around San Francisco: if they lit a fireplace, wood stove or outdoor fire pit, they would have to either take a course on the health effects of wood smoke or pay a fine.

By mid-January, the district had issued an extended spare-the-air alert to cope with a perennial Bay Area problem. The region’s air quality often plummets during the winter when dry, windless conditions concentrate tiny but harmful particles from residential wood fires, traffic and industrial sources into a thick, choking haze near the ground.

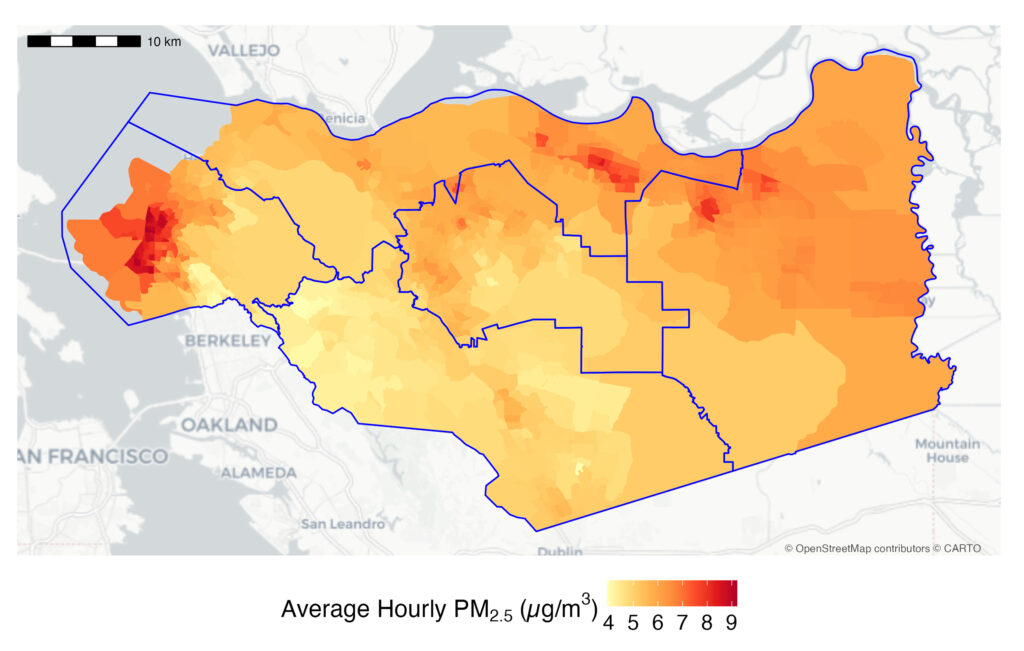

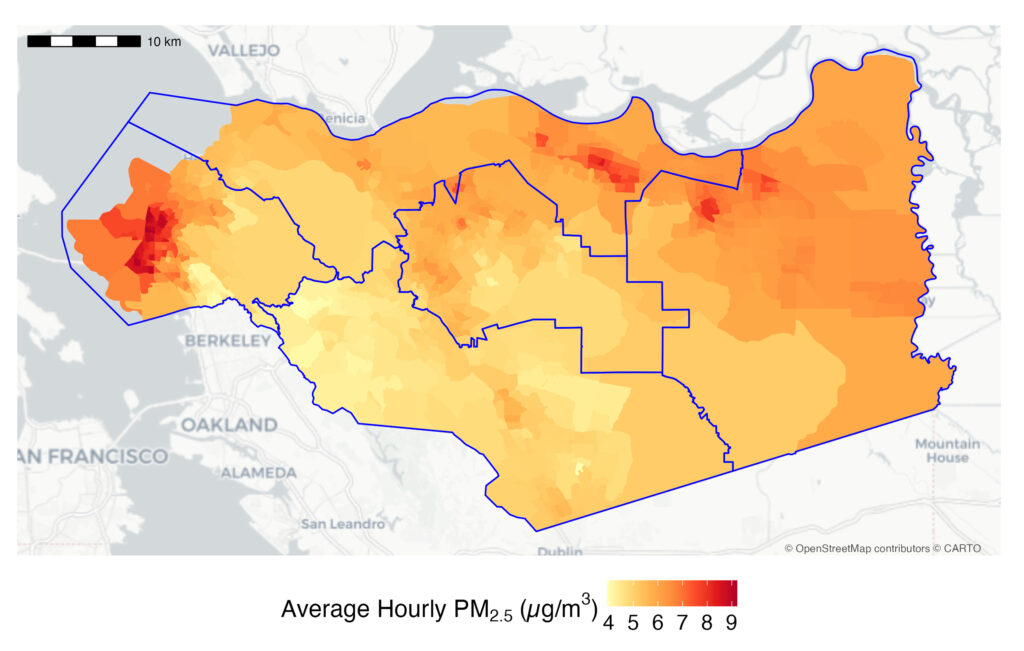

Yet patterns of pollution from fine particles, or PM2.5, and other sources vary considerably across the Bay Area.

In Contra Costa County, east of San Francisco, wood smoke and emissions from diesel trucks and other vehicles combine with particularly high concentrations of greenhouse gases and toxic air contaminants emitted by the region’s oil refineries. Several refineries operate along the county’s northern regions, including three that rank among California’s top five planet-warming polluters, data from the Environmental Protection Agency’s Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program shows. Oil and gas operations accounted for 68 percent of nearly 500 air quality violations issued since January 2025.

Both air pollution and bouts of extreme heat are projected to worsen in Contra Costa as the planet warms, compounding local health dangers.

Protecting the county’s most vulnerable residents requires knowing exactly where these environmental threats overlap, but the air district monitors PM2.5 at just a few sites in the county.

In a new report, scientists with the nonprofit PSE Healthy Energy and the University of California, Berkeley, identified climate and pollution hotspots by filling that monitoring gap over a nearly two-year period.

The team placed 50 low-cost PM2.5 sensors across the county and gathered publicly available data from hundreds of privately owned Purple Air monitors. They also used census data to evaluate demographic differences in exposure based on race, age, income and the proportion of outdoor workers in an area.

Purple Air monitors typically cost a few hundred dollars, and tend to be used in whiter, richer areas. So the researchers deployed a network of low-cost sensors in disadvantaged neighborhoods, guided by representatives from historically under-monitored communities and state data that flagged census tracts with high cumulative environmental and socioeconomic burdens. The team worked with volunteers to place monitors in homes, schools, restaurants and local institutions like fire departments.

There’s a growing body of research that emphasizes hyperlocal air-quality trends over the span of a couple years, said Sebastian Rowland, a study co-author and expert on the health impacts of air pollution and climate at PSE Healthy Energy. “This hyperlocal scale really shows the neighborhood-by-neighborhood differences in PM2.5 exposure.”

The study identified air-pollution hotspots in five cities, including Richmond, home to the massive Chevron refinery, and nearby San Pablo.

Even short-term exposure to air pollution increases the risk of death for people with underlying heart and lung conditions, studies show.

Hispanic and Black populations, on average, live in areas with higher PM2.5 exposures than their white or Asian counterparts, the team found. Black and Hispanic residents also live in regions with higher heat exposures, along with children under age five, adults over 65 and outdoor workers.

The study measured just one pollutant, but vehicles and industrial sources of PM2.5 typically emit other air contaminants at the same time, said Karan Shetty, a report coauthor with PSE Healthy Energy who studies the public health impacts of industrial sources of pollution.

“Cars and trucks emit PM2.5 along with nitrogen oxide, which forms ozone in the atmosphere,” he said. “These emissions will be in the same places and likely the same people are being exposed.”

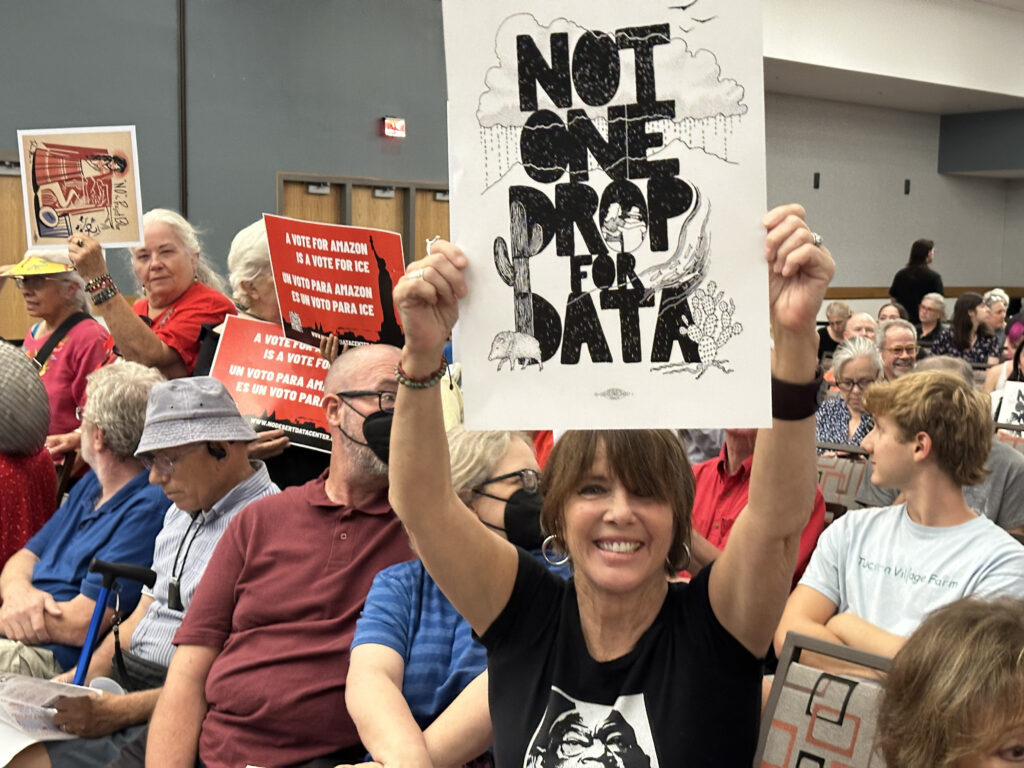

The study uses groundbreaking approaches to mapping PM2.5 levels, said Shoshana Wechsler, co-founder and coordinator of the Sunflower Alliance, a nonprofit dedicated to ridding the Bay Area of fossil fuels.

“It departs from the usual top-down approach by employing methodology fundamentally based on listening to the community,” Wechsler said. “And the result is the most accurate portrait of pollution impacts in Contra Costa that we’ve had thus far.”

Synergistic Effects

As global temperatures continue to climb from unchecked fossil fuel combustion, wildfires have become more frequent and destructive, while heat waves have become more common. Wildfire smoke from hotter, bigger fires adds to chronic pollution from heavy vehicle traffic, oil refineries and other industrial sources, boosting levels of PM2.5, which causes cardiovascular and respiratory disorders, cancer and poor birth outcomes.

“When you’re exposed simultaneously to high levels of heat and air pollution, there is a synergistic effect,” Rowland said. “The effects are much worse than either one on its own.”

Even short-term exposure to extreme heat and air pollution at the same time substantially increases the risk of death, studies show.

The team had intended to study county birth outcomes in relation to heat and PM2.5 exposures, but the Environmental Protection Agency canceled the grant last year, said John Balmes, a physician and environmental health expert who would have handled the analysis.

“The EPA funding mechanism was climate and health, which is why we didn’t have funding for almost a year,” said Balmes, professor emeritus at both the UCSF Department of Medicine and UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health. “Climate change is something you can’t even talk about under the Trump administration.”

The EPA restored the group’s funding after UC researchers prevailed in a lawsuit. But by then it was too late to determine whether prenatal exposure to heat and PM2.5 increased the risk of problems like preterm birth and low birth weight, potential precursors to serious chronic conditions later in life.

Still, Balmes said, the report provides the best mapping of the environmental health impacts of air pollution and higher temperature that’s ever been done for Contra Costa County.

“We went into this expecting low-income folks of color to have the greatest risk, and we more or less found that,” Balmes said. “But we did find that folks in much of western Contra Costa County had cooler temperatures, so they didn’t have the double whammy that folks farther east did.”

Although temperatures have risen across much of Contra Costa County over the past 20 years, more high-heat events are happening in the eastern portions of the county. These regions are also getting hotter faster than the county’s western side, the team found.

“This raises concerns about the health and well-being of residents in these areas, particularly as this trend is likely to worsen over time, based on projections of future extreme heat,” the report warned.

The urban communities of Antioch, Oakley and Pittsburg in the eastern part of the county are experiencing both elevated air pollution levels and more extreme heat days. They also have high proportions of residents with insufficient resources to mitigate risks.

This region also has fewer tree-filled spaces to provide shade for residents seeking relief from the heat. And pockets of poverty, even in places with cooler temperatures like Richmond, limit residents’ ability to buy air conditioners or filters to reduce their exposures.

The Bay Area Air District was pleased to provide feedback and guidance over the course of the project, a spokesperson for the district said in a statement. “We are excited to see the release of the final report and applaud efforts to bring additional attention to environmental and health disparities in the Bay Area.”

Reducing Risks

Beyond flagging hot spots where dangerous environmental exposures overlap with resource-strapped populations, the team asked community members what they thought about a range of potential risk-reducing interventions.

Other studies have analyzed air monitoring data and then told community members how to reduce their exposure to pollution, Karan said. This study differed by pairing air pollution and extreme heat exposure at very fine spatial scales while incorporating community feedback.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

The team worked with the community at every stage of the project, from determining where to locate monitors to figuring out how best to tailor climate resilience strategies to their specific needs.

“I am so impressed by the fact that PSE Healthy Energy actually followed the basic environmental justice tenet in doing this study, which is to listen to the community,” said Sunflower Alliance’s Wechsler. “Just on the basis of methodology used, not top down for a change, and radically inclusive, this sets a high bar.”

Wechsler was also buoyed to see the report confirm that Contra Costa’s Climate Action and Adaptation Plan is on the right track.

“But the absolute erasure of environmental justice priorities by the federal government is having a terrible trickle-down effect,” she said. “And the county is going to need serious funding to implement its own policies.”

The Trump administration canceled hundreds of grants designed to improve environmental quality and resilience to extreme weather in March, including a $19 million grant to Richmond.

In 2020, the Contra Costa County Board of Supervisors declared that the county was facing a climate emergency that “threatens the long-term economic and social well-being, health, safety, and security of the County, and that urgent action by all levels of government is needed.”

Several of the county’s plans include measures designed to improve air quality and help residents cope with extreme weather along the lines of those identified in the report. The county is working to minimize heat333-island effects by increasing tree canopy and requiring cool roofs in building codes; maintaining community resilience hubs as well as a heat and air-quality education and emergency preparedness plan; and providing access to high-efficiency air purifiers for low-income residents with asthma or other respiratory conditions through programs like the Asthma Initiative.

When there’s not a wildfire or refinery flare or incident, diesel emissions from freeways, rail yards and the Port of Richmond are the largest source of chronic PM2.5 pollution, Balmes said.

Beyond needing to accelerate the transition to electric vehicles, he said, portable air purifiers with HEPA filters effectively reduce PM2.5 that infiltrates homes. “And the county could subsidize people in the most impacted areas who can’t afford to buy them on their own.”

The team sees the report as a starting point to identify ways to reduce the health risks of colliding climate threats. Next steps should include more community “listening sessions,” the authors said, to better understand specific challenges facing residents in different neighborhoods.

The Air District is expanding its efforts to monitor more pollutants in the air near refineries, while working with communities to guide its localized or source-oriented air monitoring systems. Such programs will give a more complete picture of air quality, particularly in overburdened neighborhoods, the district spokesperson said.

Balmes hopes the primary message from the report comes through loud and clear.

“Climate change is real,” he said. “It increases extreme heat days but also increases air pollution, in part because people have to adapt to the extreme heat, and that means we have to generate more electricity.”

Ultimately, he said, “we need clean transportation and clean power generation to mitigate climate change.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,