Planet China: Fourteenth in a series about how Beijing’s trillion-dollar development plan is reshaping the globe—and the natural world.

QADIRABAD, Pakistan—Only a few weeks to wrap up a lifetime. The thought crossed Muhammad Imran’s mind and lingered as he prepared in November to depart the country with his family, perhaps for good.

Disheartened by Pakistan’s chronic political and economic troubles, Imran decided to look for a better future elsewhere. But the other, more immediate worry was less than a mile from his family’s neighborhood in the agricultural heartland of the nation’s largest province: a giant coal-fired power plant.

“We never felt comfortable here. This environment … it’s not just about us. Everyone here breathes the same air,” Imran, 33, said somberly as his wife, Asma Rafique, comforted the younger of their two children.

The couple stepped into the courtyard of their government housing colony, awash in afternoon light that glared against a wall of broken bricks and scattered weeds. The Sahiwal power plant towered over the neighborhood, a thick white plume rising from one of its massive smokestacks.

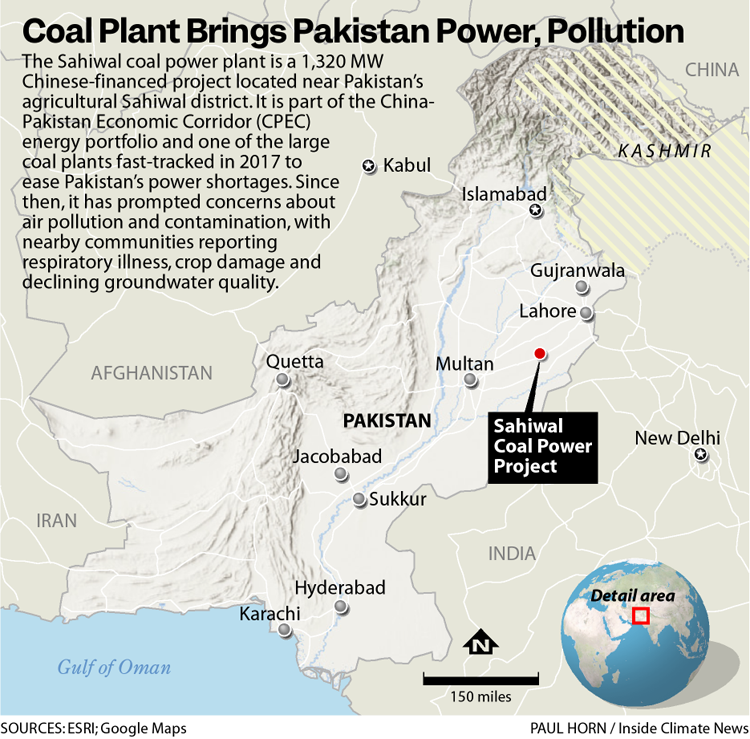

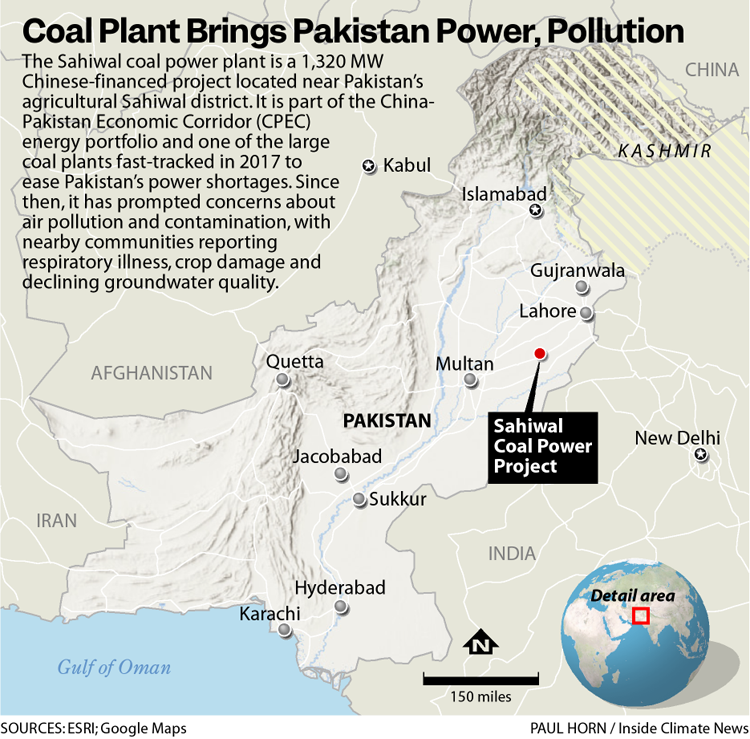

In 2015, as countries increasingly retired coal power plants because of their health- and climate-damaging pollution, Pakistan struck a deal with China for eight new ones—starting with Sahiwal. The logic was simple: Generate more electricity fast to end destabilizing blackouts in Pakistan, while producing a return for China as part of its massive infrastructure push across the Global South.

A decade later, seven of those power plants are running and Pakistan faces new problems. Ballooning debt from the energy complexes has jacked up electricity costs, fueling a surge in rooftop solar that in turn means less money to address the debt. Communities near the plants bear the brunt of the new pollution. And many regions still experience rolling blackouts, now triggered not by lack of electrical generation capacity but because the country doesn’t have the cash to fully run the plants.

China describes its Belt and Road investment campaign as a major win for lower-income countries long exploited by the West. But a number of the projects have harmed surrounding communities, an investigative series by Inside Climate News found. And in Pakistan’s case, the power-plant deal built on the playbook developed by Western companies operating in the country years earlier.

Imran and Rafique moved to Qadirabad several years after the power plant began operating in 2017. They and their children started experiencing lingering respiratory and skin symptoms and could get no explanation for the cause. For a while, before deciding they had to leave, they tried to spare their children’s health by spending weekends with relatives, some 50 miles away in a city called Chichawatni.

“We leave every Friday and come back on Monday. That way our kids get to breathe fresh air back in our family home,” Rafique said. The air in Qadirabad is so polluted, Imran said, that his mother, who has chronic asthma, cannot visit for even a few hours.

A pharmacist at the local clinic described similar experiences. “Half the patients who come now complain of cough or eye redness,” said the man, who asked not to be named because staff is not supposed to speak with the media. “It wasn’t like this before the plant.”

How a Coal Plant Landed in the Middle of Farmland

Pakistan’s electricity shortages have persisted for decades. But the hours-long rolling blackouts that started in 2011 and continued into 2015 were among the worst in recent memory, plunging communities into darkness, shuttering factories and stalling economic growth. Under pressure, the conservative Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) party then in power scrambled for fixes to calm public anger and reboot the economy.

China offered one.

Its talks with the PML-N government for the multibillion-dollar Pakistan component of the Belt and Road, the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor, or CPEC, included the slate of coal-fired plants.

The nations struck a deal on the CPEC framework in 2015, but the year before, top Pakistani leaders had already held a groundbreaking ceremony for the Sahiwal plant to celebrate what they saw as an economic turning point. An environmental impact assessment for the project, prepared for the plant’s operator, argued that hydropower would be too slow to develop and domestic gas too unreliable. A coal plant with technology that required imported fuel was the only viable response to the “acute power shortages,” the assessment concluded.

Built for $1.9 billion by a subsidiary of the state-owned China Huaneng Group, the plant was one of many Belt and Road projects constructed by Chinese firms across the Global South.

Afia Malik, an Islamabad-based energy economist with the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, a government research organization, said the decision to rely on imported coal that Chinese investors found more viable than Pakistan’s domestic resource locked it into foreign fuel dependence and price volatility.

The terms of the contracts have caused even more problems for Pakistan.

The government agreed to pay the plant operators for 85 percent of the electricity each facility is capable of generating, whether that amount was generated or not, she said.

Pakistan already had experience with that “take-or-pay” structure. Pushed by the World Bank and other multilateral lenders to address electricity shortages in the 1990s with privatization, the country agreed to contracts with Western independent power producers that also guaranteed minimum payment based on capacity. But that threshold was 65 percent, not 85, Malik said. And even so, Pakistan is paying billions each year for 1990s-era plants operating at low levels.

Both the older and newer contracts require payments in dollars, a further problem for Pakistan as its currency value sinks. All of that adds to the country’s “circular” energy debt, which refers to overdue payments from electricity users including households and businesses as well as transmission and distribution-related losses piled across the power system, impacting the government’s ability to pay power producers on time. That cycle has metastasized overtime and cannot subside without systemwide upgrades and reforms, experts say.

The International Monetary Fund said in a January 2024 report that the country’s circular debt stood at 2.6 trillion Pakistani rupees, about $9 billion in U.S. dollars, equivalent to 2.5 percent of gross domestic product.

Pakistan’s planning failures are to blame for the financial impacts of the CPEC plants, in Malik’s view. “[The] Chinese government didn’t ask us to take it. We asked them to come and invest here.”

Ayesha Ali, an associate professor at the Lahore University of Management Sciences who studies electricity access and structural failures in low- and middle-income energy systems, said Pakistan missed a chance in the mid-2010s to build a more balanced energy mix.

“A slower path, but perhaps more sustainable … would have integrated more renewables,” she said from her Lahore office. She pointed to hydropower, utility-scale solar and distributed mini-grids as options overlooked in the rush to end blackouts.

In a written statement, officials at Pakistan’s power ministry said CPEC coal plants “largely resolved” the country’s blackouts related to insufficient capacity. But the government doesn’t have enough money to fully run those plants because the cost of fuel, its transport and related services are so high. That, along with problems such as climate-driven breakdowns, is driving current-day outages, the ministry said.

Pakistan’s rapid, citizen-led shift to rooftop solar—with inexpensive panels from China—is both a symptom and a catalyst of this dysfunction. As more households and businesses go solar, the country’s electric utilities have fewer paying customers, further worsening their financial troubles.

The Clinic in the Shadow of the Smokestacks

When the Sahiwal power plant project in Punjab province received approval, the region’s Environment Protection Department laid out compliance requirements, including routine monitoring to ensure air quality standards would not be exceeded. The operator was also instructed to promptly address complaints from neighboring residents.

But when some local community organizations raised concerns about the plant’s impact on public health and the environment, they said the operator didn’t respond directly but rather through Chinese media platforms, little-known forums and paid content, insisting that emissions remained well within limits and complied with local laws. The groups weren’t able to confirm that: Officials at the Punjab Environmental Protection Department in the provincial capital referred them to annual compliance reports that are not independently verified or even publicly available, the local advocates said.

The Punjab Environmental Protection Department and the office of the provincial minister, Marriyum Aurangzeb, did not respond when asked by Inside Climate News whether any emissions monitoring, groundwater sampling or similar periodic testing has been done as required. They also did not say whether they would make any results public or comment on whether the government has a plan to address public grievances and health concerns.

In the absence of public monitoring and compliance data, the best way to grasp the coal plant’s impacts is to visit the modest rural health center in village 55/5L, a short drive from the government colony where Imran and Rafique lived with their two young children.

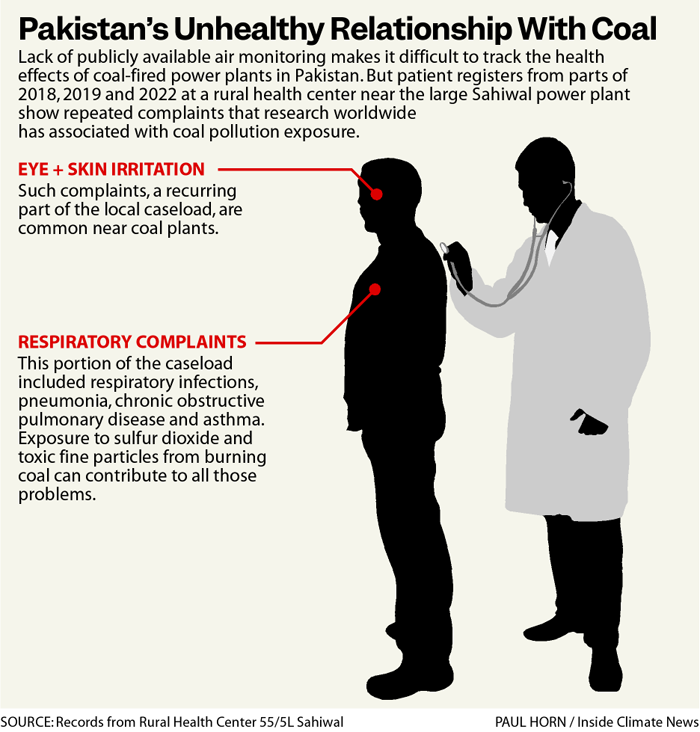

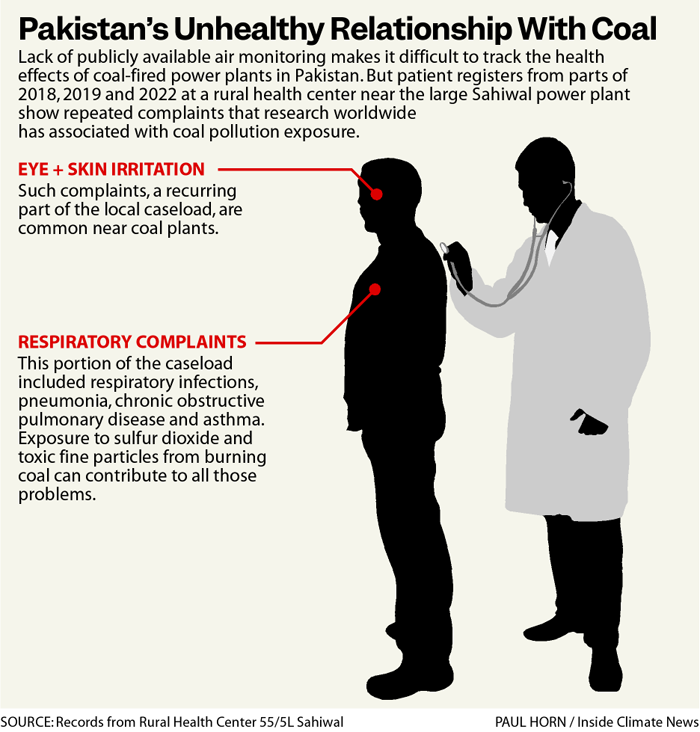

Dr. Samir Baig, a young medical doctor posted here last February, said the facility has no reliable system for tracking illnesses over time, but patterns in the steady stream of cases jump out to him.

“I’ve seen a clear burden of skin issues, and a close second is flu and sore throat. I’m seeing this from the very beginning,” he said. Upper airway irritation is also common.

The clinic’s dispenser, who joined the staff several years before the plant began operating in 2017, offered a clearer sense of how illness patterns have evolved over the years, describing common ailments like skin irritation, congestion and asthma. “In my experience, the frequency of these burdens has increased, not lessened, since the power plant started working here,” he said, asking not to be named because he was not supposed to talk with the media.

The problems both men described, even susceptibility to influenza, are what decades of health research has shown a community can expect when exposed to the toxic particles and sulfur pollution from burning coal. Coughing, throat irritation, recurrent chest infections and asthma‑like episodes are noted by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the World Health Organization and toxicological assessments of sulfur dioxide and particulate pollution.

At the village 55/5L clinic, handwritten pages in English and Urdu note the illnesses reported by patients and medicines they were sent home with.

In 2018 and 2019, the first full years after the plant began commercial operation, respiratory illness was the most common complaint noted in the daily outpatient registers, documents reviewed by Inside Climate News show. Many pages are densely filled with the names of villagers from the plant’s immediate vicinity.

Children under 5 came in frequently with acute respiratory infections and fever, while older adults showed up with wheezing, shortness of breath and other chronic chest complaints.

On several days in July and September 2018, more than half the entries involve breathing complaints. None of the handwritten entries discuss causes, pollution or otherwise.

Inside Climate News was also able to review the 2022 records. In July, August and September of that year, the forms record several hundred cases of “acute (upper) respiratory infections” each month, alongside smaller but persistent numbers of pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma and suspected tuberculosis cases.

Only gastrointestinal problems such as diarrhea and peptic ulcer disease rivaled respiratory illness in scale, and skin conditions like scabies trail behind them. Taken together, these reflect the infectious‑disease burden typical of rural Punjab, said a local health department expert who asked not to be named. What stood out was that respiratory diagnoses remained near the top of the list.

These clinic numbers are one of the few datasets reflecting health conditions near the Sahiwal plant. In communities exposed to coal combustion, public‑health experts typically watch for three early markers: persistently high rates of acute respiratory infections, more frequent flare‑ups of asthma and obstructive pulmonary disease and a noticeable burden of eye and upper‑airway irritation. All appear in the clinic’s registers.

None of that information can establish causation. What it shows are troubling patterns.

And independent research suggests that residents are being exposed to pollution that can harm their health. Findings published in the PLOS One journal in 2024 showed elevated levels of coal-related heavy metals in soil and crops across villages closest to the plant.

Plant operator Huaneng Shandong Ruyi (Pakistan) Energy and its parent company, China Huaneng Group, did not respond to repeated requests for comment by Inside Climate News. The Chinese embassies in Islamabad and Washington, D.C., also did not respond.

Asked about conditions near the Sahiwal plant, Shezra Mansab, Pakistan’s minister of state for climate change, said Pakistan is “committed to environmental justice.” Provincial environmental agencies are responsible for enforcement but concerns will “take some time” to address, she said.

Locked in a Vicious Circle

Weak oversight isn’t limited to the coal plants’ pollution. A 2020 government-commissioned inquiry found that numerous power producers under CPEC “were earning profits far in excess of what was allowed,” with inflated project costs and contracts that “transferred most of the risk to the Government of Pakistan” and worsened the circular debt. The report urged officials to renegotiate the deals in the public interest.

As policymakers in Islamabad weigh contract revisions and early coal retirements, public officials and experts are asking why Pakistan didn’t learn from its expensive 1990s private power deals before locking the country into another exorbitantly expensive 30-year fossil fuel generation cycle.

Pakistan’s former climate change minister, Malik Amin Aslam, who was not part of the administration that negotiated CPEC power deals, sees those coal plants as a “big liability” and called the Sahiwal coal power plant “a project … done with criminal neglect.”

In a phone interview with Inside Climate News, Aslam said the plant “was clearly sited in the wrong place” and is “having disastrous effects on the people who are living around it and the agriculturists.” He said underground water sources and crop yields have both declined since the plant opened.

“It is the heartland of Pakistan and it has had disastrous results,” he said bluntly. Now the country is trapped in what he called a “very bad situation,” paying for power it no longer needs from multiple new coal plants as consumers rapidly migrate to rooftop solar.

Pakistan is negotiating to repurpose or retire some of the coal plants early, particularly Sahiwal, Aslam said. Both Pakistani business interests and outside experts say a deal to fix the country’s coal-energy conundrum would accelerate the country’s shift to renewables. But Aslam warned the talks will be difficult, given the “very luxurious” 30-year contracts to Chinese investors. “Why would they walk away from future profits?” he said.

The view from a residential compound near the Sahiwal coal plant. Many homes here show signs of wear and long-standing neglect despite the industrial buildout around them. Aman Azhar/Inside Climate News

Mansab, the minister of state for climate change, defended the country’s heavy dependence on imported coal while acknowledging planning flipflops underpinning CPEC’s power projects.

“Pakistan was in dire need of stable energy,” she said in a phone interview. The coal plants, she maintained, were built at a time when “there wasn’t so much policy … for renewables” and therefore were necessary. She did not dispute that the same projects are now at the core of Pakistan’s fiscal troubles.

Mansab also conceded that the planning assumptions underpinning CPEC deals did not materialize. The expected industrial growth “did not happen,” she said, leaving the country with more power plant capacity than it needed.

Mansab resisted calling the episode a failure of governance, saying the contacts reflected “global financing norms at that time.” But she acknowledged that Pakistan is now “relooking” at these deals both domestically and in discussions with foreign partners, including China. Without offering any specifics on timelines or possible terms of renegotiation, she said, “We cannot afford any more loans.”

Meanwhile, Pakistan’s power ministry is trying to address some of the structural problems that began with the 1990s-era power plants. Officials said in a statement that they have terminated five “redundant” independent power producers that predate CPEC, saving an estimated $210 to $215 million annually, and renegotiated terms with 14 others to save even more per year.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

Davide Zoppolato, a researcher affiliated with Mapping Global China, which looks at Beijing’s overseas engagement, sees that 1990s privatization as the prelude to Pakistan’s current woes. China stepped into the policy space already shaped by Western lenders, he noted. In his view, China made a clear choice to profit from a vulnerable system.

“China was there to make money,” he said, adding that it’s not taking responsibility for the fallout.

Chinese President Xi Jinping pledged in 2021 to stop financing new coal abroad, but so far that has not helped Pakistan extract itself from CPEC coal plants.

Zoppolato said China is shifting toward a “small and beautiful” development model after years of frustration with corruption and instability in countries like Pakistan. But whatever the next phase of CPEC looks like, China now dominates both ends of Pakistan’s energy transition. It owns a major slice of the fossil generation fleet and is “almost the sole seller of solar panels” flooding Pakistan’s rooftops, he said.

That combination of long-term fossil contracts and reliance on Chinese solar imports leaves Pakistan more dependent on Beijing than before. “There’s no easy way out,” Zoppolato said.

What strikes Muhammad Tayyab Safdar at the University of Virginia about the CPEC coal plants is how the contracts maximized returns no matter how ill-thought-out any of the projects were. He said it amounts to 17 to 20 percent guaranteed profit rates, which “you wouldn’t get anywhere else in the world.” That means the investors have already recovered most of their investments, he said, even as Pakistan struggles to run the plants.

The Sahiwal coal plant, in his view, is a clear example of bad planning. The decision to build it in the middle of Punjab’s farmland “doesn’t make sense,” he said, but Pakistani officials wanted it near population centers to cut transmission losses.

He doubts Beijing will budge on restructuring or retiring Pakistan’s coal plants. “Why would they?” he asked.

What Was and What Comes Next

In 2022, Asma Rafique was posted in Qadirabad as a veterinarian at a government-run facility. The modest housing came with the job. What she didn’t realize was how difficult it would be to live next to the massive coal-burning power plant that shared a boundary wall with her residential colony.

Imran, her husband and a fellow veterinarian, had just found a job in Oman. Over the next three years, as he tried to find a good place to raise his family, he moved to Ireland and then to Australia, coming home every few months for brief visits.

Sitting in the courtyard of their Qadirabad home as the sun set on one of his final days in the country, Imran felt the weight of his family’s imminent move to Australia. They would escape the plant’s pollution, he said, but what about their neighbors?

“All the people living here, we are a family here. So I think about them as well,” he said. “It’s our collective issue, our national issue, so that should be addressed.”

It was beyond him why government officials approved such costly and dirty operations or why the plants are still running today. “I would tell them that solar and wind will be the cheapest and environment-friendly options. This will be my message for them.”

He wished he didn’t have to leave his parents. “Any expat would love to come back,” he said, adding: “I will come back.”

A few hundred yards away, the coal plant kept running, its steady hum bleeding into the evening and a trace of exhaust suspended over one of its cooling towers.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,