Reporting for this story was supported by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

WINKLER COUNTY, Texas—The first sign of trouble appeared in 2003 when the water samples came back salty.

This remote corner of West Texas, known as the T-Bar Ranch, had long served as the City of Midland’s insurance policy for water security. Midland purchased 20,000 acres spanning Winkler and Loving Counties in 1965, waiting for the day it would need to pump water from the property.

Extra salts in the aquifer was not part of the plan.

The city’s investigation soon landed on Heritage Standard Corporation as the prime suspect. The small Dallas-based company operated oil and gas wells and a disposal well near Midland’s water source.

In 2007, the city filed a formal complaint with the state, alleging that Heritage Standard’s injection well had contaminated the groundwater. The Railroad Commission of Texas, which regulates oil and gas, ordered the company to remediate. But in 2010, Heritage Standard filed for bankruptcy.

The saga continues to this day. The pollution is still being cleaned up more than two decades after its discovery. Heritage Standard also abandoned six inactive wells, known as orphan wells, that the state is now on the hook to plug. These are among the more than 11,000 orphan wells on the list for plugging in Texas.

Protecting water from pollution is one of the Railroad Commission’s primary mandates. But T-Bar Ranch shows how costly, complicated and time-consuming it can be to clean up groundwater pollution left by oil companies. The bankruptcy process allowed Heritage Standard to shed troublesome assets. But the pollution persists. This is one of more than 500 active cases of groundwater contamination attributed to oil and gas activities, going back decades, that the Railroad Commission oversees.

A representative of Heritage Standard’s executive Michael B. Wisenbaker Sr. declined to comment.

“The existing regulatory framework has been effective,” said Railroad Commission spokesperson Bryce Dubee. “The agency’s critical mission is to protect public safety and the environment, and protection of groundwater is our primary concern with regard to the commission’s federally approved Underground Injection Control (UIC) program.”

Oilfield contamination can threaten precious water supplies in a growing, thirsty state. In November 2025, Texans voted to dedicate up to $1 billion annually to the Texas Water Fund to grow the state’s water supply.

“We’re putting one billion dollars toward finding new supplies of water,” said Julie Range, policy manager at Commission Shift, an organization focused on reforming the Railroad Commission. “We should be protecting every drop of water we have—that should include these operations that we know are risky.”

Where Oil and Water Mix

The 2024 Texas Joint Groundwater Monitoring and Contamination Report lists 531 current cases of groundwater pollution linked to the oil and gas industry under Railroad Commission jurisdiction. Another 348 cases of contamination are listed as “inactive” because the Railroad Commission decided to leave the pollution in place. Injection wells, spills and pipeline leaks are some of the ways oil and gas companies have contaminated groundwater.

Most of these incidents do not impact groundwater currently used for domestic consumption. But T-Bar isn’t the only place where oil and gas activities are suspected to have impacted public water reserves. The Colorado River Municipal Water District, which provides water for Big Spring and Odessa, found benzene in a water well in 2012.

Public water sources have tested positive for industrial contaminants more than 200 times around Texas, according to the state’s contamination report. It is unclear how often this pollution comes from the oil and gas industry, which in addition to fossil fuels produces billions of gallons of highly toxic wastewater, called produced water, primarily disposed of underground in injection wells.

Finding suitable drinking water in the Permian Basin isn’t easy. Aquifers in West Texas are often slightly saline or laced with naturally occurring arsenic. The first Permian oil wells were drilled in the 1920s and hundreds of thousands now pockmark the surface. The risk of contamination is ever present. More insidious is the vast quantity of produced water, the salty byproduct of drilling, that was disposed of in open pits for decades. These pits, banned in 1969, allowed pollution to leach underground.

The Texas Water Commission, a precursor to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, wrote in 1989 that brine, another name for produced water, is one of the “principal pollutants” of the state’s aquifers. The report cautioned that contaminated groundwater plumes could exist below old pits but concluded it was not “practical, nor economical” to remediate these areas.

As one Texas Monthly writer put it in 1991, “Having polluted water, a good lawyer, and a pending lawsuit against a major oil company has become a tradition in West Texas.”

The problem continues. A 2020 paper in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health found that groundwater quality degraded in the Permian Basin between 1992 and 2019. The authors found two primary contributors: chemical fertilizers in agriculture and spills in the oil and gas industry.

Improperly plugged oil and gas wells have also allowed naturally occurring salty groundwater to migrate upward and contaminate shallow groundwater, according to the regional water plan. More recently, Permian Basin landowners Ashley Watt and Schuyler Wight have brought attention to groundwater contamination on their ranches.

But the experience of Midland, a city at the heart of the Texas oil industry, demonstrates the broader risk of oil and gas drilling in close proximity to water wells.

T-Bar Ranch

Midland sits on the edge of the Chihuahuan Desert and receives on average 13 inches of rain a year. The city’s primary water sources are reservoirs on the Colorado River.

Before and after Midland purchased T-Bar Ranch, scores of oil and gas wells were drilled on the property.

In Texas, the Rule of Capture dictates that a landowner can pump water from the underlying aquifer without restrictions unless there is a groundwater district. But owning the land doesn’t convey the mineral rights, including the right to drill for oil and gas. Therefore, Midland must cooperate with companies that drill for oil and gas and dispose of their waste at the property.

“They have mineral rights. We have water rights,” Midland utilities director Carl Craigo explained in an interview. “We have to become a team.”

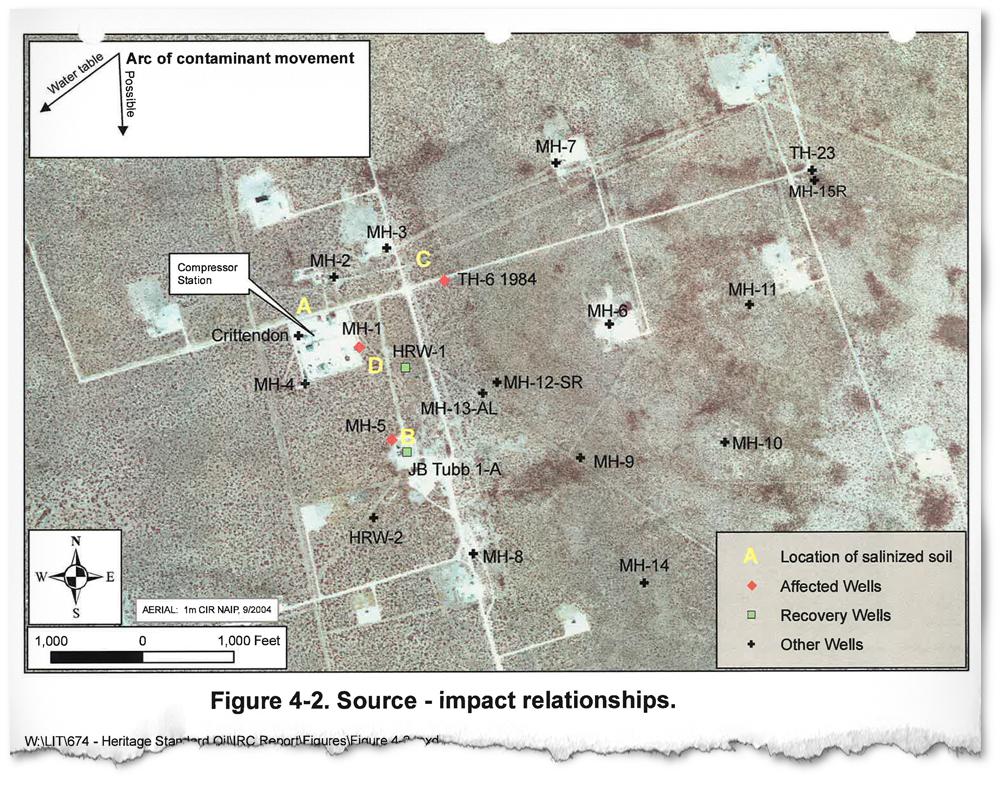

In 1994, Heritage Standard repurposed a 1970s oil well at T-Bar Ranch, called J.B. Tubb 1-A, as an injection well for the disposal of produced water. The wastewater is injected into underground cavities that are significantly deeper than groundwater reserves.

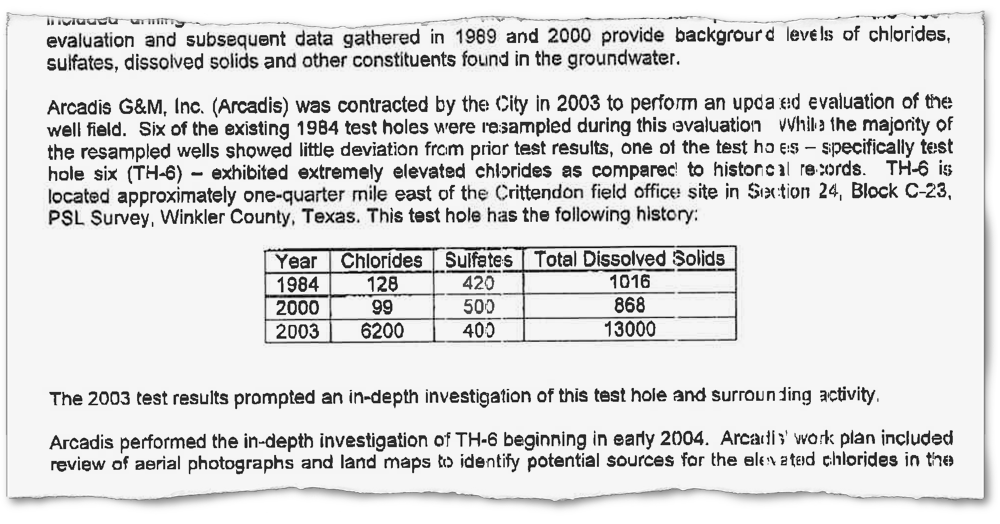

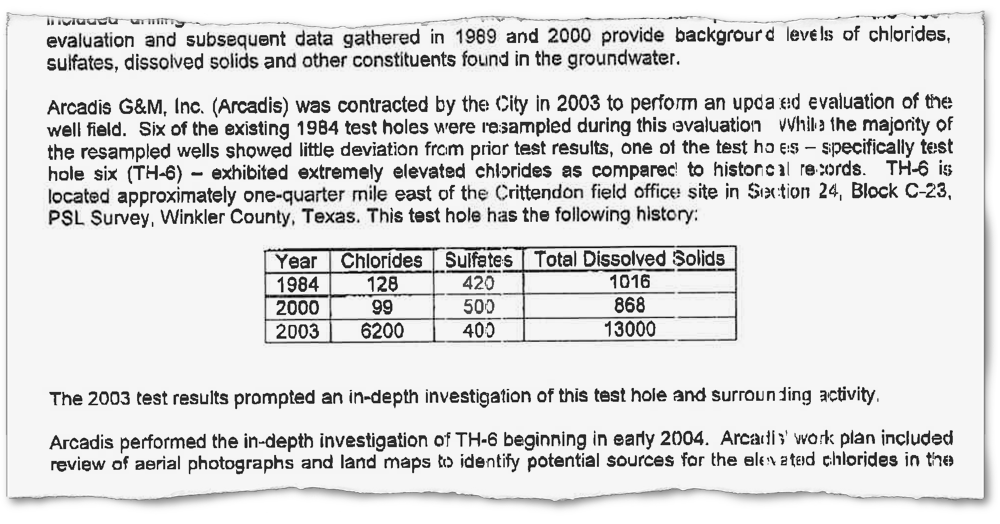

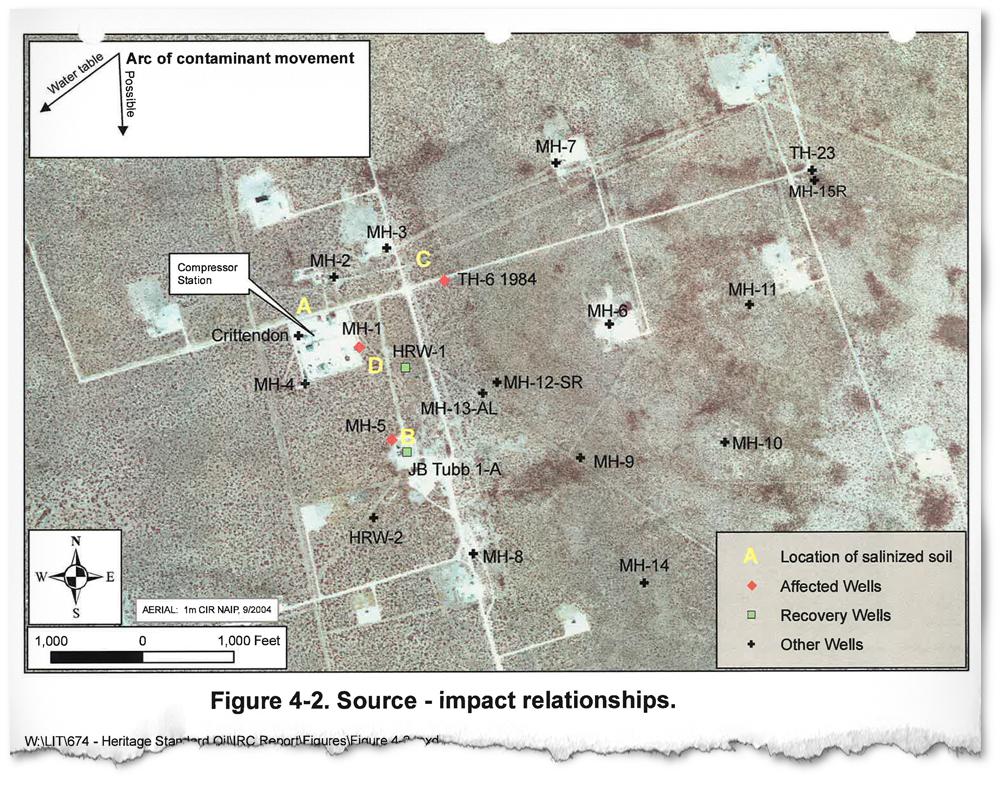

In 2003, Midland did a round of water sampling at the T-Bar wells. The results from Test Hole 6 were alarming. Chlorides and total dissolved solids, signatures of produced water, had shot up since the last round of tests in 2000. The city investigated the source of the sudden salinization.

Injection wells have several layers of casing to prevent the waste from leaking into aquifers. But testing on the well in 2007 determined that several holes had formed in the Tubb well’s casing sometime around 1999. By the time Heritage Standard shut down the injection well in 2006, environmental contractors later estimated, between 50 million and 63 million gallons of produced water had already potentially leaked into shallow underground formations. Other investigations considered the possibility that produced water dumped on the ground could have caused the contamination and estimated a much lower volume of wastewater released.

In May 2007, Midland lodged a formal complaint with the Railroad Commission, accusing Heritage Standard of polluting the groundwater. Kay Snyder, the city utility director, wrote in the complaint that the contaminated groundwater plume posed “a significant threat” to fresh groundwater at T-Bar Ranch.

“We have alerted them to the problem,” Snyder wrote to the regulators. “However, they have not seen the urgency of addressing the issue, nor do they admit to any responsibility in causing the contamination.”

The Railroad Commission approved a remediation plan that involved monitoring the plume, pumping contaminated water out of the aquifer and injecting it into a nearby disposal well. Heritage Standard’s insurance company assumed some of the costs.

The Railroad Commission did not issue fines to Heritage Standard for the pollution.

On September 8, 2010, the Railroad Commission requested Heritage Standard conduct a full investigation to delineate the groundwater pollution plume.

The company filed for bankruptcy in the Northern District of Texas less than one week later. According to legal filings, Heritage Standard had spent millions trying to re-open a plugged well to drill for gas in Winkler County. The filing said the failed drilling effort had left the company with $11.6 million in debt and no income from the well to pay it off.

“Kicking the Can Down the Road”

The boom and bust cycle of the oil industry makes it particularly prone to bankruptcies. The law firm Haynes Boone found that between January 2015 and July 2020, 115 exploration and production companies in Texas filed for bankruptcy. That was the most of any state, with the 36 bankruptcies in corporate haven Delaware a distant second. These companies can leave behind unplugged wells, water and soil pollution and crumbling infrastructure.

Chapter 11 bankruptcy sets a structure for companies to prioritize creditors and shed burdensome assets. The process is described as a “waterfall” in which one class of creditors is paid before the funds flow down to the next class of creditors.

Inside Climate News consulted court filings and public records from the Railroad Commission to reconstruct the bankruptcy proceedings for Heritage Standard.

Dozens of creditors lined up to get paid back, including the company that was owed nearly $5 million for drilling the gas well.

Secured debt—backed up by collateral—takes priority in bankruptcy. In theory, when a company goes bankrupt it still must cover environmental liabilities. But environmental cleanup costs, an administrative debt, are a lower priority than secured debt.

Midland and the Railroad Commission made their case to the bankruptcy court for cleanup money to remediate the groundwater and plug Heritage Standard wells.

Midland, the Railroad Commission, Heritage Standard and its insurance company eventually reached a settlement. In August 2013, the bankruptcy court released its final decision. Heritage Standard would put $1.025 million in an environmental escrow to fund remediation and well plugging, far less than Midland’s claims of $6.5 million.

“The settlement significantly benefits the Estates by limiting and capping the exposure from the Environmental Claims, which could have all but eliminated recoveries for certain creditors in the case,” Judge Harlin D. Hale wrote at the time.

In other words, environmental costs were capped to ensure that Heritage would pay back creditors it owed. The final judgement stipulated that the Railroad Commission would cover remediation and well plugging costs if the environmental escrow ran out of money.

Kelli Norfleet, an attorney and chair of the restructuring group at Haynes Boone in Houston, told Inside Climate News that there often isn’t much money left by the time environmental costs are being considered during bankruptcy.

“If the money is gone, the money is gone,” said Norfleet, who was not involved with the Heritage Standard case. “So you have to look to other sources to try to cover those costs.”

East Texas lawyer Jason Searcy, who acted as trustee for the Heritage Standard case, died in 2019. Joe Marshall, the attorney representing Heritage Standard, could not be reached for comment. Judge Hale has retired and did not respond to questions.

Clark Williams-Derry, an energy finance analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, said that the U.S. bankruptcy system prioritizes getting companies “back up and running” even if they do not have enough money to cover their operating costs and environmental liabilities.

“Oil and gas assets that really should be retired—because there’s no economic benefit to them at all—they will just keep going, keep chugging along,” Williams-Derry said. “Chapter 11 is a way of kicking the can down the road.”

“Bankruptcy becomes a bailout for oil and gas companies,” he said.

Midland Takes Over Cleanup

While the bankruptcy case progressed, a deep drought gripped West Texas. In spring 2011, Midland imposed water restrictions as reservoirs dipped dangerously low. By the end of that year, it had rained a mere five and a half inches and Midland needed water

Midland rushed to build a 60-mile water pipeline to the ranch. In May 2013, the pipeline came online and water began flowing. Midland drew from an uncontaminated part of the aquifer. But city officials worried that, if the contamination wasn’t cleaned up, it could reach their wells.

The Railroad Commission worked with Heritage Standard to implement the remediation plan. The full $1.025 million from the environmental escrow was spent on environmental assessment and well plugging, according to the Railroad Commission’s Dubee. The Railroad Commission spent an additional $462,000 from its cleanup fund, which comes from fees and penalties paid by industry, on the T-Bar remediation.

Letters to the Railroad Commission from a firm hired by Heritage and its insurance company said the remediation effort had steadily decreased chloride levels and that the contamination was contained. The plume, which covered an area of up to 15 acres, did not contain hydrocarbons or heavy metals, according to the consultants.

They wrote that they expected the remaining plume of contaminated water to mix and blend with the non-contaminated water to the point that the plume would no longer be distinguishable. “On this basis, Heritage considers that the remnant Tubb plume poses no threat to the [City of Midland] water supply,” the consultants wrote.

During a May 13, 2015 meeting, representatives of Heritage, the Railroad Commission and Midland discussed leaving “the small residual chloride plume” and compensating Midland monetarily, according to a letter written a few days later by the consultants.

The Railroad Commission was open to this idea, according to emails obtained via record requests. Commission staff later wrote in an email that the RRC considered leaving the pollution in place, referred to as “control,” to be an “acceptable” outcome.

Midland officials later objected. “[Midland] is not convinced that the extent of the plume has been appropriately characterized or that remediation is complete,” a hydrologist working for the city wrote the Railroad Commission in July 2017.

In September 2018, city manager Courtney Sharp sent a letter to the commission expressing “great concern” that the contamination was “migrating towards the heart of the City’s water supply at the T-Bar wellfield.”

Midland petitioned to take over the remediation. The commission approved Midland’s new plan to install “interceptor wells” between the contamination and the city water wells.

Texas law describes the goal of groundwater policy as ensuring “the existing quality of groundwater not be degraded.” It says groundwater should be kept “reasonably free” of contaminants that would interfere with present or future uses. The state uses a risk-based approach to determine whether groundwater contamination should be cleaned up or left in place, known as “control.”

While Midland officials were still concerned that the contamination could impact their water supply, the Railroad Commission considered the “control” option an acceptable outcome. Midland then stepped in to ensure remediation continued—on its own dime.

Commission spokesperson Dubee said that the fact that Midland assumed responsibility for the cleanup was not an indication that regulations had been ineffective. He re-iterated the “control” option would have been an “acceptable regulatory endpoint.”

Current Remediation Plan

The pandemic delayed Midland’s implementation plan. In 2022, the city approved a contract for up to $3.5 million to begin; the full process could cost up to $9 million.

In March 2023, Midland utilities director Carl Craigo addressed the city council in a drab conference room, clicking through slides. Craigo explained that the city plans to sell water pumped out of the aquifer to oil companies to recoup remediation costs. Oil companies can drill with water that is too salty for municipal use.

During the meeting, Craigo described the Railroad Commission remediation efforts as “very small.”

“What they had the company doing just drained the settlement of money to a point where the city needed to take it on,” he explained.

“The Railroad Commission wasn’t our friend back then,” quipped one council member under his breath.

In an interview, Craigo said that the city took over the remediation to ensure its water supply would be protected.

“It was not enough to make a difference,” he said of the remediation overseen by the Railroad Commission. “It was really just enough to monitor it.”

Monitoring and delineation, in which the contours of the plume are mapped, are important components of groundwater remediation, the commission spokesperson told Inside Climate News.

Midland, with a population of 143,000, now relies on T-Bar for about a third of its water supply. Craigo said that communication with the other oil companies operating at T-Bar remains essential to protecting that water source.

“They luckily come through us and make sure what they’re doing coincides with what we’re doing,” he said.

The City of Midland denied requests to tour T-Bar Ranch. In late November, trucks barreled down the two-lane highway leading to the property, dodging gaping potholes. Oilfields stretch to the horizon in all directions. The ragged highway shoulder drops off precipitously into the desert sand.

From the highway, a battered metal sign reading “Heritage” points down a private road to the Midland wellfield. It’s the only indication of the contamination that threatened the city’s water supply and the perpetrators who were allowed to walk away.

In response to a detailed list of questions for this story, Midland communications officer Stewart Doreen said, “we have addressed this issue in the past and nothing further to add at this time.”

Leaving Behind Orphan Wells

Post-bankruptcy, Heritage Standard became a company in name only. It stopped filing state paperwork or reporting oil and gas production after 2013.

Dwayne Purvis, of Purvis Energy Advisors in Fort Worth, said it is common for small oil companies to stop operating without filing for bankruptcy. “If there’s no means of paying creditors, or if they don’t have very many creditors, they will just fold and disappear and never go through bankruptcy court,” he said.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

That appears to be what happened to Heritage Standard. But the company still had one parting gift for the state of Texas.

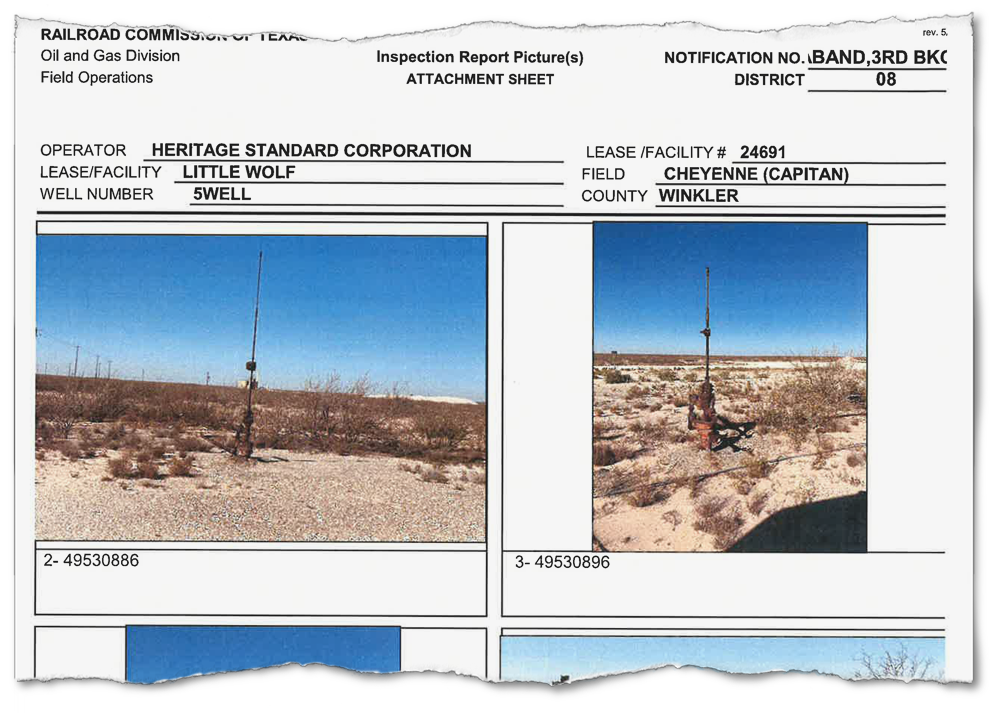

The state requires wells to be plugged after they stop producing oil or gas. During the bankruptcy, the Railroad Commission had identified 16 wells that Heritage Standard would continue to operate but was unlikely to plug and set aside funds in the firm’s environmental escrow for plugging.

Nine wells were plugged between 2014 and 2017, commission records show; another became a monitoring well. That left six unplugged wells in Heritage Standard’s name.

The Railroad Commission considers a well orphaned once it has not been producing oil or gas for at least 12 months and the operator’s organizational report has been delinquent for longer.

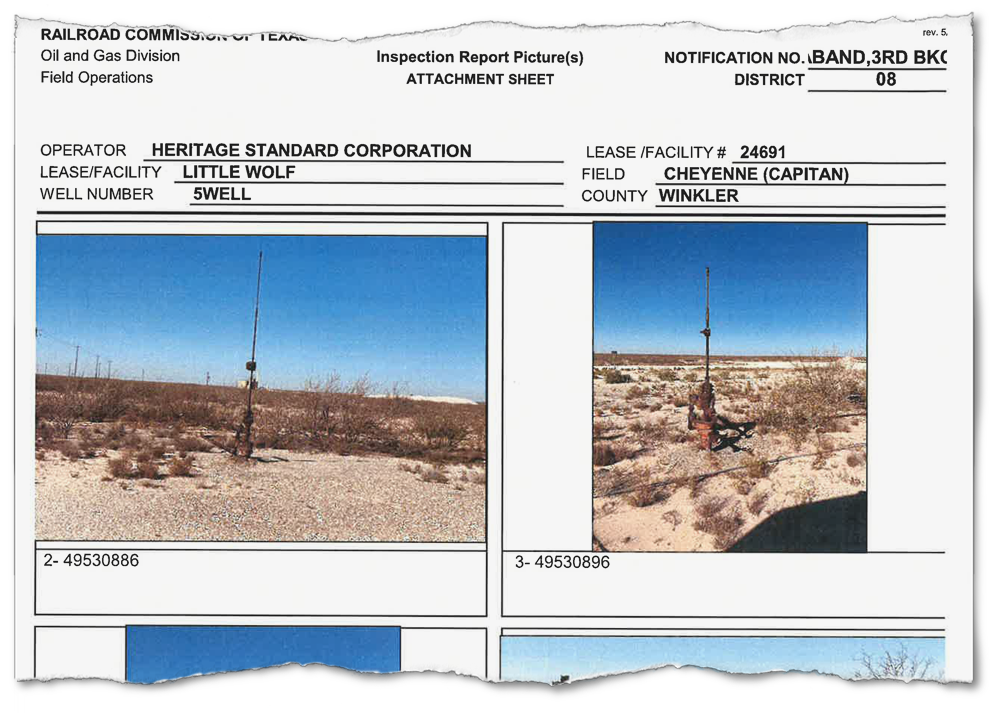

Commission inspectors repeatedly visited the unplugged wells. The commission issued violations and ordered the company to bring the wells into compliance.

The six wells were finally added to the Railroad Commission’s list of orphan wells and classified as priority level 3, with 1 being the highest and 4 the lowest.

Midland’s Craigo said the city monitors wells that may need to be plugged at T-Bar. Geolocation data indicates Heritage Standard’s six orphan wells are on city property, but the City of Midland declined to answer questions about the wells.

Statewide, the backlog of orphan wells is the highest since 2006. The commission warns that orphan wells can be a conduit for groundwater contamination.

“Projecting Problems”

The Railroad Commission recently secured more funding from the state legislature to plug orphan wells. But the extent of groundwater contamination has received little attention. Cases like Heritage Standard are buried deep in state records or decade-old court filings.

Still, Commissioner Wayne Christian, a Republican from East Texas, dismissed the problem at an April 2025 monthly meeting of the three elected commission leaders.

He and his fellow commissioners had sat silently as members of the public approached the lectern. Commission Shift’s Julie Range briefly mentioned polluted aquifers during her comments about the agency’s annual monitoring and enforcement plan.

Christian cut in.

“In Texas, where have we polluted underground drinking water for a municipality where it’s irreparable?” he asked Range.

“Midland,” she said.

Frowning, Christian asked for more examples. He scoffed at the idea that “one well” was a problem if the city could drill others. “Where I see a problem is us projecting problems when they don’t exist,” he sniped. “To the public, it does a disservice to represent an overage of problems.”

Christian did not respond to questions for this story.

Christian’s comments focused on existing municipal water supplies. But Texas law also requires the future use of water to be protected. Polluting groundwater today limits supplies for tomorrow.

As rivers and reservoirs dry up and climate change increases water stress, Texas will increasingly rely on aquifers. Groundwater is especially important for Texas during droughts, like the one that sparked panic in 2011.

Texas has ample reserves of oil and gas. Economists project the Permian Basin will remain the country’s most productive oilfield for decades.

But projections for water in the arid region are less rosy. Fracking wells have increased nationwide water use by seven times since 2011 because of new drilling techniques called “monster fracks.” The region’s water planning district projects that, if additional water sources aren’t developed, Midland could face water shortages as soon as 2050. For other cities in the Permian Basin, that day could come as soon as 2030.

While Texas has reached new heights in oil and gas production, good water is getting harder to find.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,