Supreme Court Associate Justice Samuel Alito’s seat was empty when the Supreme Court heard arguments Monday in an important case over the oil and gas industry’s responsibility for damage to the Louisiana coastline.

Last week, the high court’s clerk notified the parties in the case that Alito would not participate due to his financial interest in ConocoPhillips, the parent company of Burlington Resources Oil and Gas Company, one of the firms accused of extensive wetlands destruction that has left Louisiana more vulnerable to costly storms.

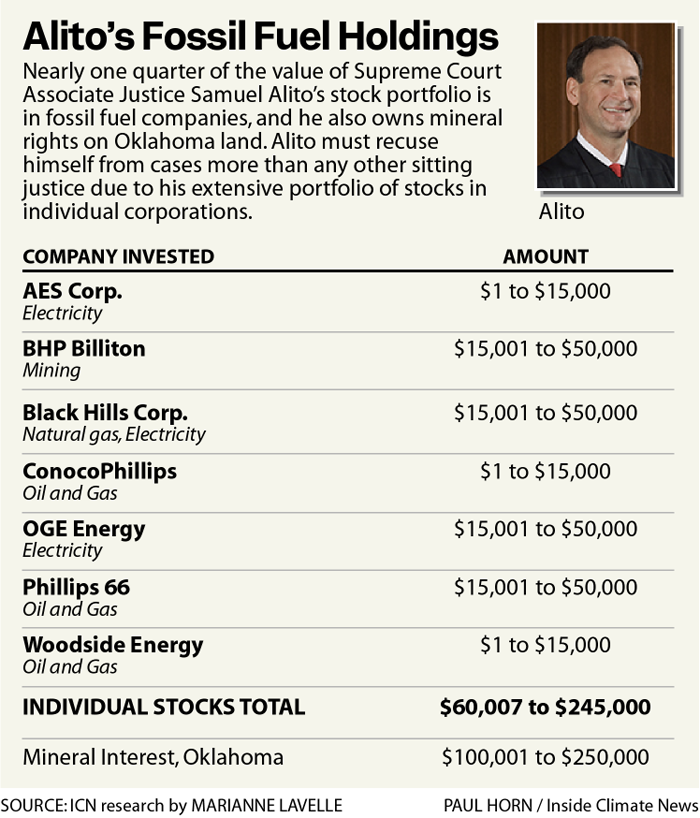

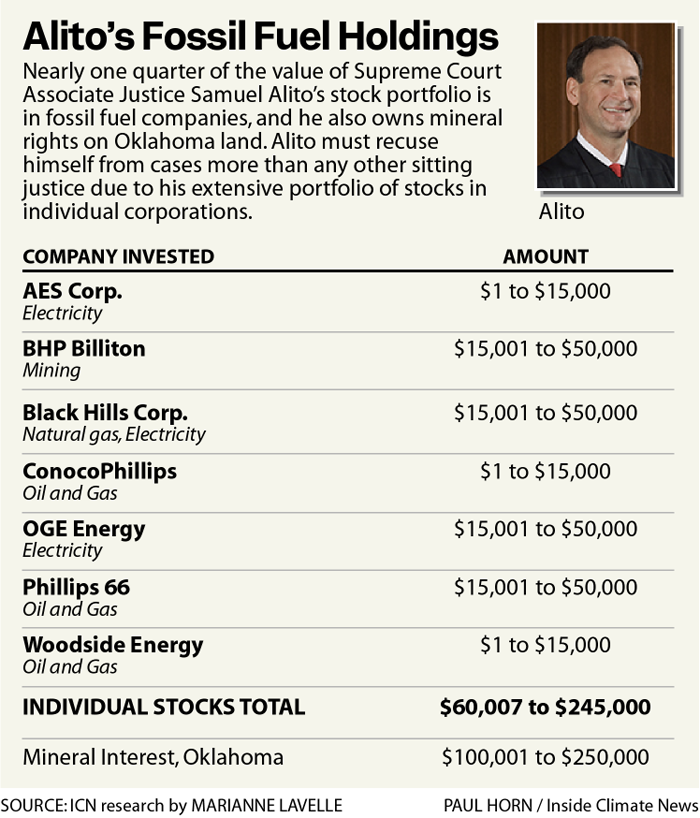

Alito owns $15,000 or less in ConocoPhillips stock, part of a portfolio that includes seven fossil fuel industry equity investments he holds worth from $60,000 to $245,000, according to his most recent financial disclosure.

The late recusal announcement—Alito did participate last year in the court’s decision to hear the Louisiana case—underscored how his decision to hold an extensive portfolio of stocks in individual companies sets up a potential for conflicts of interest that is unique on the high court.

Alito has recused himself 10 times this term and 53 times over the past three terms due to his investments in 25 companies, which are valued at as much as $1 million, according to tracking by the nonprofit group Fix the Court. The watchdog group found Alito is the only justice that has had to step back from cases related to individual stock holdings in the past three terms, and as a result he recuses himself more often than any other justice. His account for nearly one-third of the recusals in the past three terms.

Even Small Holdings Raise Alarms

Federal law requires U.S. judges, including members of the Supreme Court, to disqualify themselves from any proceedings in which their impartiality “might reasonably be questioned.” Although that phrase leaves room for interpretation, the law spells out several bright line rules. One of them is that judges must recuse themselves when they or their spouse hold any financial interest—no matter how small—in a company that is a party to the proceeding.

But in the Louisiana case that bright line became murky. On May 7, 2025, prior to the second of four private conferences where the justices were to consider whether to hear the case, one of the six oil company petitioners, Burlington Resources, notified the Supreme Court that it intended to withdraw from the petition. According to Alito’s recusal letter, he initially decided not to recuse himself because the Court had indeed dismissed Burlington from the case on June 2. The letter said a later briefing in the case revealed that Burlington would continue to be a party to the litigation in the lower courts.

That means that Alito would have participated in the justices’ June 12 private conference, where they decided to grant the oil companies’ petition that the court hear the Louisiana case, a decision they announced four days later. The votes on such decisions, called grants of certiorari, generally do not become public, but the Supreme Court only grants cert in cases where at least four justices are in favor of doing so.

Read More

After Losing a Climate Case in a Louisiana Courtroom, Chevron Wants a Change of Venue

By Lee Hedgepeth

The fact that the Supreme Court decided to hear the case was a preliminary win for the oil companies that brought the Louisiana petition. In Chevron v. Plaquemines Parish, the oil companies are seeking to have a slew of lawsuits they face over coastal environmental damage removed from state court to federal court. It’s a procedural issue with potentially huge implications. In Louisiana state court, the oil companies face hundreds of millions of dollars in potential liability for failing to restore wetlands damaged by decades of dredging of canals, well-drilling and wastewater dumping. The oil companies argue that because they had federal contracts during World War II—providing aviation fuel for the Allied forces—the cases belong in federal court. Analysts believe the oil companies see federal courts as more sympathetic to their argument that they are owed protection from liability.

Stephen Gillers, professor emeritus at New York University School of Law and a longtime legal ethics expert, said Alito’s recusal letter, although short, offered much more detail than such announcements typically do. Supreme Court justices generally do not state their reasons for disqualifying themselves from cases, which can happen because of family conflicts or their participation in a case when they sat on the lower courts. Gillers said Alito likely spelled out the history of Burlington Resources’ partial withdrawal from the case because he “had to explain why he was recusing now, when he had not recused earlier.

“Alito runs into this problem a lot because he has broad investments, so it comes up again and again,” Gillers said. “There’s some who believe, as I do, that federal judges should limit the scope of their equity investments in companies to avoid unnecessary or disruptive recusals, and to some extent, many do.”

Most of the Supreme Court justices, including Alito, have holdings in diverse mutual funds that do not raise the same conflict of interest issues. Indeed, the only other justice who has reported any individual stock holdings at all was Chief Justice John Roberts, who has shares in a semiconductor services company, Lam Research, and the biotech company Thermo Fisher. But Alito’s stock holdings are so numerous the question of his recusal comes up every term.

“The interesting thing about this case, and it’s something I’ve been troubled by for a very long time, is why Justice Alito continues to hold stock in large publicly traded companies that regularly have cases before the Supreme Court,” said Arthur Hellman, professor emeritus and legal ethics expert at the University of Pittsburgh. “It is particularly troubling and anomalous.”

Alito’s office did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

Unlike at the lower courts, at the Supreme Court there is no one who can replace a justice who recuses himself or herself. When only eight members hear a case, there is the risk that a lower court’s decision could be affirmed by an equally divided Supreme Court. “That means there is no precedent and we go a little while longer without an answer to an important legal question,” Hellman said.

“It seems to me that if you accept that proposition that the rules governing disqualification should be a little bit more forgiving because Supreme Court justices can’t be replaced, it seems to me that it follows that the justices are obliged to carry out their lives in ways that don’t require recusal,” Hellman said.

The “First and Final” Word on Recusal

Charles Gardner Geyh, a legal ethics expert at Maurer School of Law at Indiana University Bloomington, said the rationale behind allowing stock ownership by federal judges is that a policy that is too restrictive would discourage people from serving as judges.

“I think there’s this sense that when judges ascend the bench, there are sacrifices they have to make, but they shouldn’t be obliged to make sacrifices so extreme that it makes holding judicial office less attractive,” Geyh said. “They should be able to do certain things the way ordinary people do, as long as they step aside when their financial lives get in the way of their impartiality.”

Geyh said he sees an irony in how the law treats even minimal ownership of stocks as the pivotal determinant of conflict of interest, while other activities that raise far greater concern are no bar to participation in cases.

“What it means is that if Justice Alito owns one share [of a stock in a party to a case] worth $15 he will step aside, but he can fly pro-Trump flags until he’s blue in the face,” Geyh said. He was referring to the controversy that erupted over news that an upside-down American flag—a symbol of the “Stop the Steal” movement—had hung outside Alito’s home in January 2021, when Trump was fighting the results of the 2020 election. Alito said the display was his wife’s decision, and he subsequently voted with the majority in its 6-3 decision granting Trump broad presumptive legal immunity for acts that took place when he was in office.

Fossil fuel stocks make up nearly one-quarter of the value of Alito’s individual stock holdings. He also owns a mineral interest in Oklahoma land worth $100,000 to $250,000, according to his financial disclosure. And Alito for years has voted reliably in favor of the interests of oil, coal, gas and electricity interests like those in his portfolio. In the landmark 2007 Massachusetts v. Environmental Protection Agency case, Alito voted with the minority, arguing that greenhouse gas emissions could not be considered pollutants under the Clean Air Act. And in 2022, he voted with the 6-3 majority to narrow the EPA’s authority to regulate those emissions.

None of the companies that Alito is invested in was a named party in those cases. And ultimately, it was up to Alito to decide whether his financial interest “could be substantially affected by the outcome” of the climate cases, in the words of the law.

“We have this unfortunate procedural sort of system in which a justice is the first and final word on his own disqualification,” Geyh said.

The risk for an appearance of conflict of interest rises proportionately with the number of individual stocks a justice decides to hold. Legal experts say it would be difficult, if not impossible, to administer any law or ethics code that sought to disqualify justices from participating in cases involving broad categories where they have individual holdings—like the fossil fuel industry—or broad issues that are important to their investments, like how the nation addresses climate change.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,