Fracking’s Forever Problem: Eighth in a series about the gas industry’s radioactive waste.

BELLE VERNON, Pa.—Off a back road in the hilly country south of Pittsburgh, a tributary to the Monongahela River runs through overgrown vegetation and beneath an abandoned railroad trestle, downstream from the Westmoreland Sanitary Landfill. On a cool day in late July, it was swollen with rain. Tire tracks through the dense brush were puddled with muddy water.

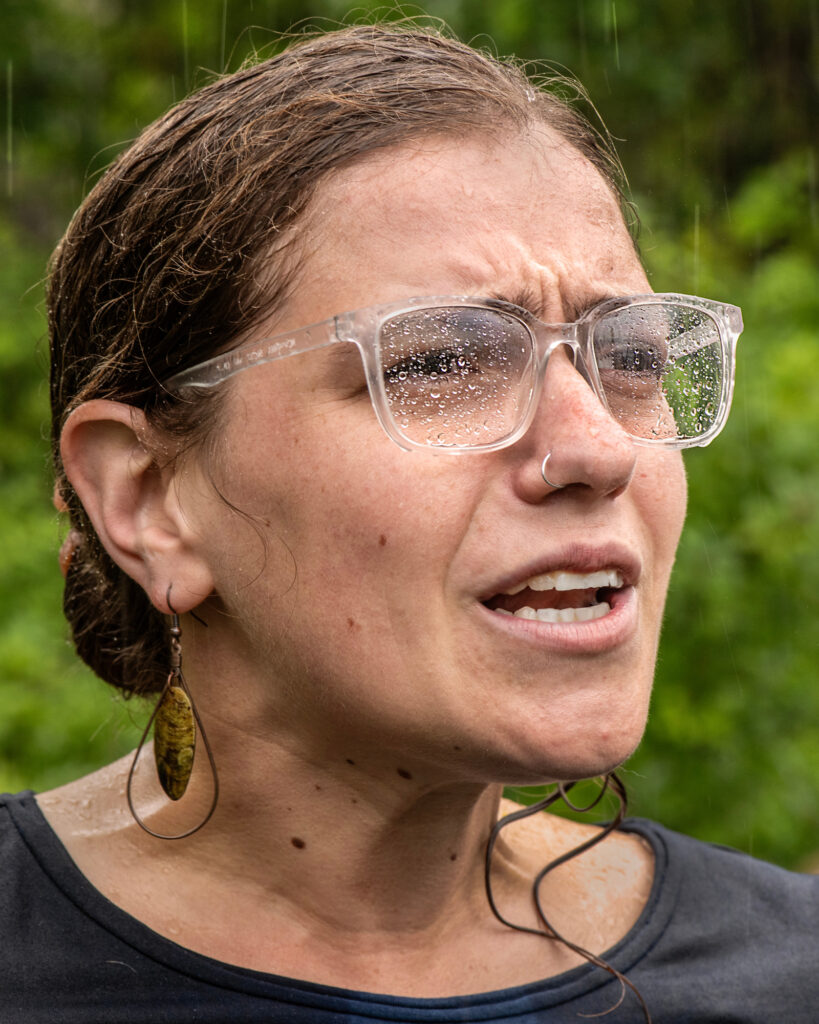

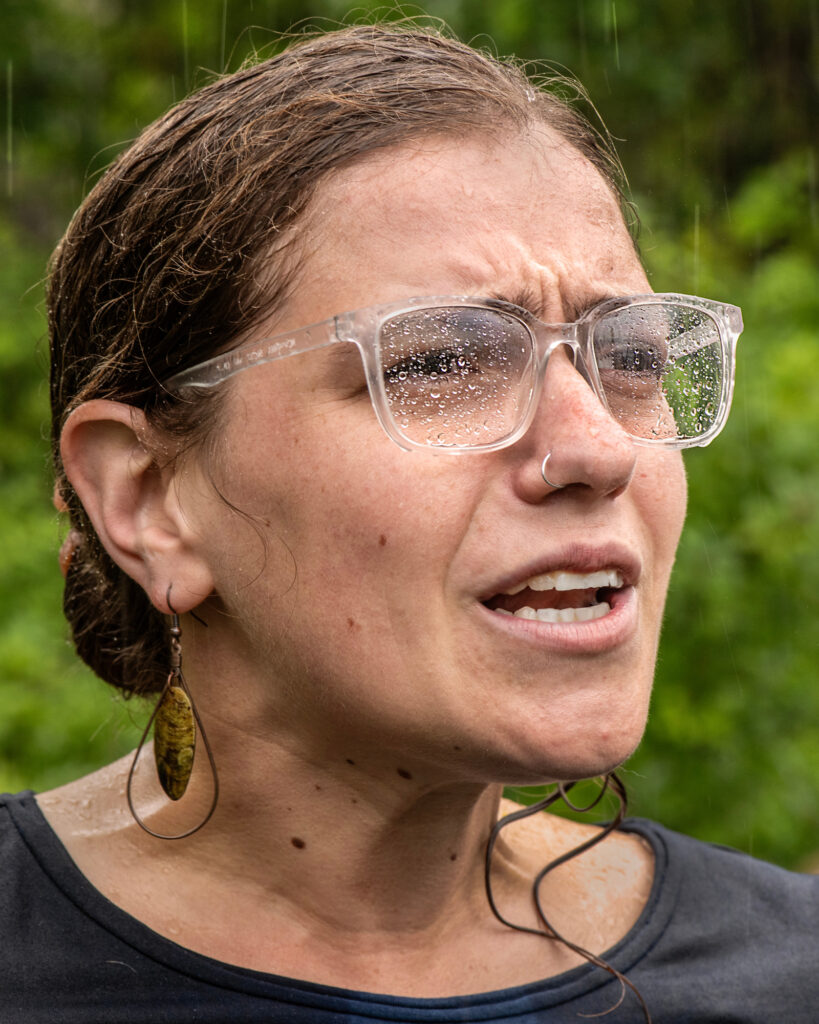

Environmental scientist Yvonne Sorovacu and local watershed advocate Hannah Hohman, her glasses spattered with raindrops, stood together under an umbrella, watching the tumble of the stream. Both women visit the landfill site regularly to collect water samples and record signs of contamination. The water here, which flows downhill from the landfill’s discharge point, is often coated with stiff globs of foam, Sorovacu said. The water upstream of the outfall is clear.

Over the course of more than a decade, as Pennsylvania’s fracking industry took off, the Westmoreland landfill accepted hundreds of thousands of tons of oil and gas waste and wastewater, toxic and often radioactive byproducts that contain elements and heavy metals from deep inside the earth and synthetic chemicals used in the drilling process. That melange can include radionuclides like radium, uranium and thorium as well as harmful substances like arsenic, lead and benzene.

After years of violations at Westmoreland, scientists and residents are keeping a close watch on the landfill, monitoring for any signs that runoff has made its way into public waterways. But oil and gas waste is going to landfills across the state, often with far less scrutiny. At least twenty-two other landfills currently take Pennsylvania oil and gas waste, and some also accept it from other states.

Oil and gas companies operating in Pennsylvania reported creating nearly 8.8 million tons of solid waste between 2017 and 2024, an Inside Climate News analysis of state records found. In an average year, that tops the waste produced by every resident and commercial enterprise in Allegheny County, where Pittsburgh is located.

Read More

Tracking Oil and Gas Waste in Pennsylvania Is Still a ‘Logistical Mess’

By Kiley Bense, Peter Aldhous

According to Pennsylvania oil and gas operators, about 6.3 million tons of this waste went to landfills in the state. But the true amount of oil and gas waste reaching the state’s landfills is likely much larger, an Inside Climate News investigation found.

And mounting evidence suggests that this ever-increasing volume is harming the streams, creeks and rivers where Pennsylvanians fish, swim, kayak and source drinking water.

In one case, at Max Environmental Technologies Bulger in southwestern Pennsylvania, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has identified the radioactive element radium, a common contaminant in oil and gas waste, as one of the likely causes of the pollution in nearby creeks. In a 2023 study, scientists from the University of Pittsburgh and Duquesne University found elevated levels of radium in the sediment downstream of the outfall at five of the landfills taking the industry’s waste. Scientists have also discovered radium build-up in freshwater mussels’ bodies and shells downstream of facilities that have treated oil and gas waste.

Four of the landfills taking oil and gas waste are out of compliance with their permits, an Inside Climate News review found.

Another seven have been out of compliance with the Clean Water Act for six months or more in the last five years.

Thirteen are discharging wastewater or stormwater into waterways the EPA classified as “impaired,” too polluted or otherwise degraded to meet water-quality standards.

Read More

Twenty Years Into Fracking, Pennsylvania Has Yet to Reckon With Its Radioactive Waste

By Kiley Bense, Peter Aldhous

State regulators have been aware of these issues for years, but little has changed in the way the waste is handled, transported or disposed of. In 2020, then Attorney General Josh Shapiro announced the publication of a grand jury investigation into fracking, which concluded that Pennsylvania had failed in its responsibility to protect the public from the environmental and health impacts of the industry. One of the grand jury’s eight recommendations for the state government called for clearer labeling of fracking waste during transport.

“Our government and the shale gas industry currently have no long-term sustainable solution to managing the toxic waste generated by fracking operations,” the panel wrote. “At the very least, the industry should be required to more safely and responsibly transport this waste around the Commonwealth.”

In Pennsylvania, contamination from fracking is layered on top of earlier waves of pollution from coal mining, manufacturing and oil drilling. One of the most prevalent sources of contamination is abandoned mine drainage, a type of pollution that comes from coal mines; like a number of other landfills in Pennsylvania, Westmoreland was built on top of a shuttered mining operation. Despite decades of clean-up efforts, more than 5,500 miles of streams in Pennsylvania are still affected by abandoned mine drainage, with devastating consequences for aquatic wildlife. Acid mine drainage, a type of abandoned mine pollution, is the second leading cause of stream pollution in Pennsylvania.

There’s been little research into what this jumble of pollutants might mean for the environment.

“When you’re mixing these things together into some kind of toxic cocktail, what are the impacts going to be on Pennsylvania’s waters?” said John Quigley, who previously served as the head of both the state Department of Environmental Protection and the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. “The cumulative impacts of this could be horrendous.”

Westmoreland did not respond to requests for comment. Max Environmental Technologies, which owns two landfills, said in a statement that its Bulger location is currently closed and its Yukon location is not accepting oil and gas waste right now.

When reached for comment about threats to the environment posed by fracking waste, the Marcellus Shale Coalition, a gas industry trade group, said that existing state and federal laws as well as companies’ safety practices “have proven to be protective of public health and the environment, and our members remain committed to operating safely, transparently, and responsibly.”

Sorovacu and Hohman saw that one side of the stream near Westmoreland was a reddish color on the July day they were collecting samples. “You can see the historic acid mine drainage here,” said Sorovacu, who works for Protect PT, a local grassroots environmental group that has been monitoring the landfill for years.

“All of our waterways are impacted by legacy [pollution], but this stream does have drainage from the landfill, so it’s one that we’re concerned about,” she said. “It’s never only one thing.”

As if to emphasize her point, the other side of the stream was a chalky white as it poured from a culvert on the opposite bank. Aluminum-heavy drainage from the coal mine beneath the landfill was a likely culprit, she said. The color acted almost like a visual calling card for water coming from the landfill.

Sorovacu’s test results taken here over the past two years show evidence of mine pollution as well as higher than expected levels of PFOA and PFOS, synthetic “forever chemicals” linked to increased risk of cancer, developmental delays and reproductive problems. Landfills are a significant source of forever chemicals. As the women watched, the gush from the culvert whitened further, like a plume of smoke unfurling underwater.

“Oh my God, I feel like it definitely got cloudier while we were standing here,” Sorovacu said, her eyes widening.

“It just got even more dramatic,” Hohman agreed.

Hohman is an environmental steward at Three Rivers Waterkeeper, a nonprofit that works to protect the watersheds of the Allegheny, Monongahela and Ohio rivers. She lives locally and responds when residents call the waterkeeper about potential contamination.

“People are on alert about this facility, and they’re concerned about what’s coming into their waterways,” she said. She hopes that more of them are starting to understand that the more the gas industry grows, the more waste it generates. That waste has to go somewhere. “It’s all connected,” she said.

Legacy pollution like acid mine drainage, meanwhile, can complicate efforts to prove the source of contamination. “It’s really convenient for operators to point to a company that doesn’t exist anymore, and say it’s because of that. Then there’s nobody to be held accountable,” Sorovacu said.

“That’s all we want, is accountability,” Hohman said. “And honestly, just to get down to the answers of what’s happening to our waterways. What impact does this have? What don’t we know?”

“Little Texas”

The Westmoreland landfill is part of a cluster in southwestern Pennsylvania that has accepted large volumes of oil and gas waste and is also situated on top of former coal mines. Arden Landfill in Washington and Max Environmental’s facilities in Yukon and Bulger are all part of that group.

“You can’t build anything in southwestern Pennsylvania without building on top of a coal mine,” Sorovacu said.

It’s not just there: Other landfills built on formerly mined land include Keystone Sanitary Landfill, near Scranton, and Phoenix Resources, in the northern part of the state.

Community activists are fighting a proposed expansion at Keystone, which accepted more than 1 million tons of oil and gas waste between 2017 and 2024, DEP records show. The landfill is close to homes, a playground and multiple schools.

In the first half of 2025, Keystone produced an average of 7 million gallons of leachate every month, according to DEP’s figures. Leachate—the liquid mixture created when rainwater flows through a landfill, picking up contaminants along the way—is another worry for environmental groups monitoring landfills that accept large volumes of oil and gas waste.

DEP fined Keystone $15,000 this year for exceeding its leachate storage capacity for several months in 2023 and 2024. At a Pennsylvania Senate hearing in 2021, then deputy attorney general Rebecca Franz acknowledged concerns about landfill leachate and fracking pollution. “There is certainly a long way to go to fix this difficult problem,” she said.

Robert Ross, a retired research ecologist who lives near Phoenix Resources in Tioga County, was part of a decades-long fight to clean up acid mine drainage in the area, including in the streams near the property the landfill now occupies. The community opposed the landfill’s construction in the 1990s, worried about water pollution, but residents lost that fight after a national corporation, Waste Management, bought the property, he said.

Waste Management now owns nearly half of the landfills in Pennsylvania that take oil and gas waste. It did not respond to requests for comment.

The Phoenix landfill has accepted more than 1.7 million tons of oil and gas waste over the past eight years, according to DEP records. It is one of the landfills where researchers found elevated radium downstream of the outfall.

Phoenix Resources’ leachate testing results from 2024 show elevated levels of the chemical barium, which is often found in drilling waste. For comparison, the test results were almost five times higher than recommended EPA standards for barium in drinking water.

Despite its long extractive past, from clear-cutting forests to extensive mining, rural Tioga County is a popular tourist destination for camping, hiking and hunting. Pine Creek, downstream from Phoenix, is a “cherished trout stream,” a place people come from all over the state to fish, Ross said.

Ross is an avid birder, and he says fracking is drowning out the sounds of nature. When drilling started about 14 months ago near his house, he wasn’t surprised when the company took baseline samples of his water in case it became contaminated. But he wasn’t expecting the light and noise pollution.

“There’s no peace anymore. I’m ready to move out of my home. I’ve been here 35 years. I just can’t take much of it anymore. It’s never-ending noise now,” he said. “I don’t hear ruffed grouse booming anymore, or deer snorting. Songbirds are harder to hear now.”

Phoenix Resources’ annual operation reports show that much of the oil and gas waste the site accepts is coming from within Tioga County and neighboring northern counties. The 161,890-acre Tioga State Forest was opened to fracking along with other public lands in 2008 by then Gov. Ed Rendell. Rendell later banned future leases, but existing leases were not canceled.

Ross said he rarely goes to the state forest now. What was once a refuge from human interference is dominated by drilling, well pads, pipelines, truck traffic and noise that extends for miles, he said.

“The place is just an industrial zone,” he said. “I call it little Texas up there.”

As natural gas development has accelerated in Tioga County, Ross is frustrated that years of conservation work to clean up the impacts of coal mining on waterways could be undone by a new source of underregulated pollution.

“It’s very distressing,” he said. “It’s just one thing after another.”

Fewer people are paying attention to local environmental impacts than there used to be. “Our watershed group is suffering from a generation gap, where there’s fewer and fewer volunteers,” Ross said. “So there’s only so much we can do. We don’t monitor the water anymore.”

Bryn Hammarstrom, a member of the Pine Creek Headwaters Protection Group, said Pine Creek is still one of the anchors of the county’s ecotourism economy. But fracking brought huge disruptions, he said, sparking financial jealousy between neighbors over gas leases, driving up rents and creating a local homeless population, and slicing through the sense of peaceful seclusion that draws people to this region. He doesn’t think many residents know about the potential harms of the gas wells’ waste or that it’s being disposed of so close by.

“People say, ‘Well, it was natural. It was there anyway,’” he said. “No, it was two miles down, locked in shale. And now we’ve pulverized it and brought it up to the surface.”

A Toxic Stew

At the entrance to the Westmoreland landfill, rainwater sluiced down the steep driveway while a parade of trucks shuttled in and out. Sitting in a car on the narrow shoulder of the road, Sorovacu considered the flow of water running off the hill.

“They’re gonna have a really hard time managing their leachate with how rainy this season has been,” she said.

One of Sorovacu’s questions about Westmoreland, and other sites that produce massive amounts of leachate every year, is whether they’ve adapted to the shifting weather patterns created by climate change. With heavier and more frequent rainfall comes more leachate to treat and dispose of, and more opportunities for the leachate to pollute.

In 2021 alone, Westmoreland held more than 10 million gallons of leachate in its storage tanks, according to the landfill’s annual operations report. In the fourth quarter of 2024, the landfill reported producing an average of more than 23,000 gallons of leachate per day.

“That landfill right now is probably doing things to control runoff that are OK or have been OK in the past,” Sorovacu said. “But even if they go by the guidelines that are given to them, will those guidelines be adequate if we keep having these intense rain events?”

The 60-year-old Westmoreland landfill became notorious in 2018, after the Belle Vernon municipal authority’s sewage treatment plant turned away its leachate for being too toxic to effectively treat. Activists contended that Westmoreland’s leachate had changed in composition because the site was accepting so much solid waste and wastewater from fracking.

Westmoreland has been the subject of four consent orders from DEP since 2020 for violations of three state laws governing water quality, waste transportation and waste management. The landfill continues to receive large volumes of oil and gas waste, accepting more than 98,000 tons in 2024, according to the landfill’s records.

The landfill is currently trucking its leachate off-site for disposal elsewhere, but it has applied for a permit from DEP to treat the waste itself and discharge the wastewater into the Monongahela.

“The landfill can’t even function properly as a landfill. Now they’re going to add this additional use to the property?” said Gillian Graber, executive director at Protect PT.

“Our view is that the landfill should be shut down, that it needs to be remediated, because it has so much oil and gas waste in it,” she said. “It’s going to keep producing toxic, radioactive leachate.”

Increasing amounts of leachate fueled by climate change would likely pose disposal problems even without the contributions of Pennsylvania’s natural gas industry. But fracking, which contributes to climate damage, has further upped the ante. Landfills’ leachate now contains elevated levels of chemicals like barium, benzene, ethylbenzene, xylene and toluene, all markers of oil and gas waste.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

Testing results for Westmoreland’s leachate submitted by the company to DEP this year show elevated levels of barium, benzene, toluene and xylenes. Duquesne University’s John Stolz analyzed the data using a method created with his colleague at the University of Pittsburgh, Daniel Bain, to assess whether a water sample has been impacted by oil and gas versus other kinds of pollution. He found Westmoreland’s recent results to be consistent with the chemical make-up of fracking waste.

“There’s an indication that this landfill leachate continues to have the characteristics of oil and gas waste,” said Stolz, an environmental engineering professor who has studied how shale gas extraction impacts water quality for years.

Mixing old and new pollution—oil and gas waste, forever chemicals and acid mine drainage swirling together—makes it harder to treat the water, he and others warn. It’s not even clear in some cases what the contamination is, let alone its effects on people, the environment and wildlife.

“You’re creating a toxic stew,” Stolz said.

Pennsylvania’s Past and Future

Outside a strip mall that houses a children’s gymnastics center, you can get a better view of the vast Westmoreland landfill next door, which is so large that it can be hard to tell where it starts and ends.

“When I first saw it from up there, I was like, ‘Where is it?’ And they’re like, ‘right there,’” said Jim Cirilano, a community advocate at Protect PT. “It looks like the landscape. Do you know what I mean? It’s so big, it was unrecognizable.”

Plants grow through the walls and roofs of abandoned houses on the edge of the Westmoreland Sanitary Landfill property.

A few homes sit just outside the landfill’s border, but two of them are empty now, Cirilano said, after they were purchased by the company. One of the houses shows signs of long abandonment, trees and vines growing through the walls. He stood beside a rusted dumpster that sat alone in the parking lot as rainwater collected on the pockmarked asphalt and trucks roving over the landfill backed up and beeped. Cirilano identified the calls of a red wing blackbird and a cardinal and watched a flock of starlings circling overhead. He speculated that the birds were finding insects to eat on the parts of the landfill where grass had grown over the waste.

“See the vultures on the roof?” he said. Three turkey vultures squatted on top of one of the nearby houses. He sniffed at the foggy air. It had a whiff of something sour. “You can smell it too, can’t you?”

Her clothes and hair sodden from the rain, Hohman pondered the future.

“I worry that we take so long to respond and adapt that by the time we do, it’s already too late,” Hohman said. “We’ve seen it over and over again. We live in this cycle of extraction.” She drew a circle with her finger in the air.

In 2024, DEP estimated that it would need $5 billion to clean up and restore streams and land damaged by abandoned coal mines. It’s far from fully reckoning with the pollution from that older boom, and now it’s well into a new one.

“As we address legacy pollution … we have new pollution,” Hohman said. She paused as a beeping truck drove over the landfill behind her. “And now we’re seeing how those things interact. What’s next?”

Inside Climate News’ Peter Aldhous contributed reporting to this article.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,