The Education of Judith Kimerling: An American lawyer’s epic struggle to stop expanding oil operations harming Indigenous peoples in Ecuador’s Amazon. Part one.

QUITO, Ecuador—On a cloudy March afternoon, I found Judith Kimerling sitting amid a sea of cardboard boxes filled with documents, books and other papers—vestiges of 30 years of her work in Ecuador. For the time being, she’s decided to keep the two nine-foot-long blow guns that were gifted to her in a storage locker.

“I haven’t figured out how I can get those home,” she said without a trace of irony.

Kimerling, an American professor with silver-gray curls and soft green eyes, is a longtime Indigenous rights and environmental activist and attorney. She is here in Quito for work on what is one of the most important human rights court cases most people have never heard of.

About seven months earlier, she appeared in a Brasilia courtroom as part of that case. Kimerling’s client, Tewe Dayuma Michela Conta, goes by Conta and is a 17-year old Indigenous girl who lived the first 6 or 7 years of her life in the Amazon rainforest with her family, uncontacted by the outside world.

The case in Brasilia, held before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, is the first in which a court of law will rule on the rights of “uncontacted” peoples, also known as “Indigenous peoples living in voluntary isolation,” though in Ecuador they are often referred to as “aislados,” the Spanish word for isolated peoples.

Ecuador’s aislados are on the verge of losing the last remaining territories upon which their physical and cultural survival depends. The fact that Kimerling’s home country has driven so much of that process is not lost on her. America has long been the biggest purchaser of the crude oil extracted from Ecuador’s Amazonian region.

The outcome of the Inter-American case, known as the Tagaeri and Taromenane Indigenous Peoples vs. Ecuador, will also have implications for dozens of similar isolated family groups and recently contacted Indigenous peoples living throughout South Americas. That’s because the Inter-American Court of Human Rights has binding jurisdiction over 20 countries including Ecuador, Brazil and Peru.

The central issue is whether the Ecuadorian government has violated Conta’s rights, and those of Ecuador’s aislados, and if so, what officials must do to remedy those violations and prevent future ones. A ruling could be issued in the coming weeks or months.

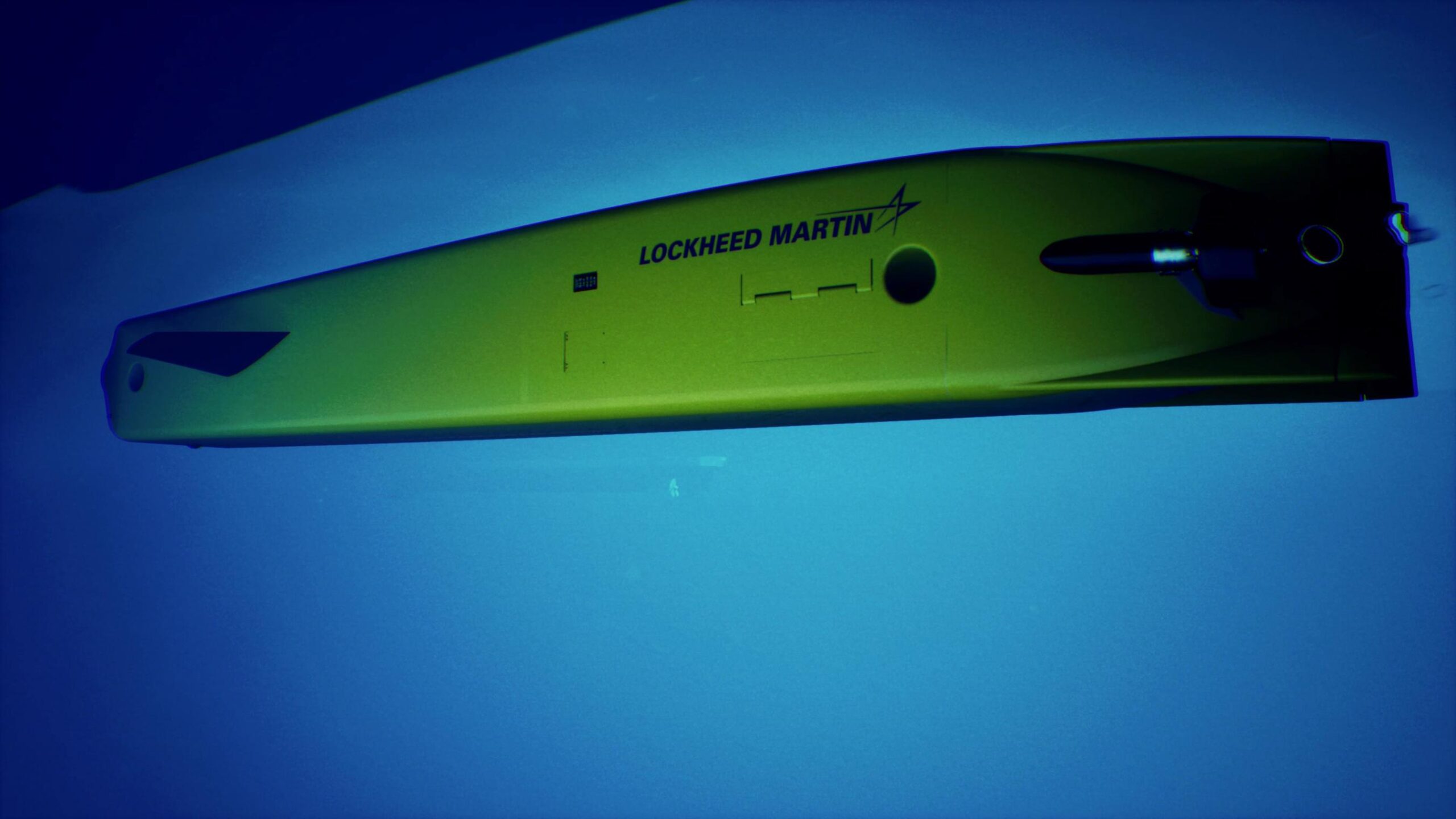

As Kimerling sees it, the case has everything to do with Ecuador’s powerful oil industry. Since the 1960s, the industry has continually expanded while Indigenous people like Conta and her family have been displaced, contaminated and attacked. Kimerling and Conta’s main aim is to safeguard as much of the remaining rainforest as possible and protect the lives and rights of Conta and the aislados.

Now, sifting through the cardboard boxes, she pulls out a copy of “Amazon Crude,” her 1991 expose of oil production in Ecuador. The book shot Kimerling to fame among environmentalists and rights activists for blowing the whistle on the operations of the American multinational Texaco (now Chevron) and the catastrophic impact the company had on Indigenous peoples.

The New York Times called the book the “Silent Spring of Ecuador ” in a nod to Rachel Carson. Kimerling’s investigation led directly to highly controversial litigation brought against Chevron on behalf of affected colonists and Indigenous people that is still reverberating, three decades later, in the U.S., International and Ecuadorian courts—litigation Kimerling refused to join for ethical and legal reasons.

Kimerling hands me the near-pristine copy of the book. Earlier, I had been grumbling that I could only find Amazon Crude for sale online from secondhand sellers who listed it for hundreds of dollars. That, I had come to learn, had an interesting backstory involving the current independent presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the National Resource Defense Council and ConocoPhillips. It is one of the many jaw-dropping anecdotes I’ve learned about Kimerling and her trailblazing career that are not widely known. Kimerling is clearly uncomfortable being the center of attention.

I ran my fingers over the crisp pages of my copy of Amazon Crude and thanked Kimerling for it. She lifted her shoulders and shrugged.

“I wish telling the story was enough but it’s not,” she said, referring to Ecuador’s still advancing oil frontier and persistent contamination.

“I haven’t yet figured out a formula to stop it.”

“So Can I”

The granddaughter of Jewish immigrants, Kimerling grew up in Birmingham, Alabama acutely aware of the privilege she had because of her white skin in the segregated Deep South. But she was also cognizant of antisemitism. Her father built a family business, the Alabama Oxygen Company, and was an early pioneer of solar energy as well as a masterful storyteller. Her mother was a leader in the Jewish community, and at the comprehensive cancer center at the University of Alabama-Birmingham Medical School, where she held numerous board offices.

Much of Kimerling’s life was conspicuously saturated in fossil fuels. She remembers going to the local Texaco gas station and seeing the company’s television commercials, which etched into her mind the image of the Texaco man, his red and white star, and the slogan, “You can trust your car to the man who wears the star.”

She attended the University of Michigan where she majored in American studies and had her first personal encounter with the limits of the law. She was fired from her cashier job at an Ann Arbor Drug store after refusing the advance of her older, male boss. Taken aback by what had happened, she paged through the phone book and called the U.S. Department of Labor to complain. Someone at the agency explained to her that she could be fired for any reason—at the time, sexual harassment was not defined as a category of sex discrimination under the law. That didn’t happen until 1980.

Knowing she never wanted to be in a vulnerable position like that again, she decided to pursue an advanced degree, thinking it would give her the economic security to always be able to say no to the boss. Law school seemed like a pragmatic next step that could open doors, and so she arrived in New Haven, Connecticut, in the fall of 1979 at Yale Law School.

From the moment she arrived, Kimerling felt as though she didn’t quite fit in with the legal culture. The school was a well-known conveyor belt to corporate firms and public offices, and proudly displayed the portraits of its renowned male alumni on the walls.

Less than one-third of her class was women, and with only one female professor, she felt for the first time in her life that sometimes a subtle message was sent that she wasn’t as good as a man. It prompted her to develop a mantra she would come back to throughout her career: If other people can do the job, so can I.

At Yale, she began to consider the type of lawyer she wanted to become. During her first year torts class, when a professor posed a hypothetical about how the students would advise a cosmetics company that produced a nail polish responsible for an allergic reaction in only some people, one classmate suggested the company place a warning on the packaging. Another student interjected—doing so could cause the company to lose market share, suggesting that the company should pay aggrieved people off rather than disclose the risk. Almost involuntarily, the words “Oh. My. God,” fell out of Kimerling’s mouth, stilling the class, she remembered.

So as her classmates marched off to interviews wearing the suits they kept in their lockers, Kimerling called occupational disease clinics around the country. She did a brief stint at a plaintiffs’ law firm involved in asbestos-related work before taking a job at the New York Attorney General’s office.

In January 1985, she settled into her new office on the 47th floor of the World Trade Center’s second tower to begin work on a case known as “Love Canal.” For her, the job would be an education in the legal and social impacts of massive amounts of toxic waste.

Love Canal

In the late 1970s, working-class families living near a former Hooker Chemical Company waste site in Niagara Falls began reporting that toxic waste had migrated into home basements and backyards. After the community demanded answers, President Jimmy Carter declared the site a federal disaster area. The state and federal governments would eventually spend hundreds of millions of dollars on remedial measures, including the purchasing of over 200 abandoned homes.

The main part of Kimerling’s job as an assistant attorney general was to help the state recover the money it had expended on remedies at Love Canal and to work with the state’s environmental experts to negotiate remedies at other waste sites. Kimerling, who has a preternatural ability to hone in on important details, learned the ins and outs of toxic waste cleanup, including what questions to ask and whom to ask them of.

Kimerling’s office did battle with Occidental Chemical Company, Hooker Chemical’s successor, over the company’s insistence that their conversations with the state be confidential. “They said they didn’t want to negotiate in a fishbowl,” Kimerling recalled. The possibility of shrouding how such a contentious agreement is made is always tempting in dealmaking, but Kimerling’s office resisted. She said the situation taught her how important transparency is and that the public’s participation put the attorney general’s office in a stronger negotiating position. “I knew we would have to defend whatever terms we agreed upon to the people in Niagara Falls,” Kimerling explained.

As her remedial negotiations wrapped up, Kimerling began to think about what was next for her.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

She had become interested in a growing fight in 1988 to stop the destruction of rainforests. That year marked a global shift in awareness around environmental issues. It was the year the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was created and when the expanding hole in the ozone layer began to capture international public attention.

Kimerling had seen the Amazon rainforest before, during a gap-year trip she took between college and law school. She had traveled on her own to, among other places, a small Ecuadorian town called Francisco de Orellana, commonly known as Coca. The city was founded in 1969, two years after Texaco struck oil in the region.

Now, nearly a decade later, at 32, she thought about Ecuador and how, with seven years of environmental law experience, she might have something useful to contribute to the world’s rainforest crusade. Kimerling realized she couldn’t contribute much from afar and decided that the best thing a North American lawyer could do was to meet local people who wanted to protect their forest and help them. She reached out to the Natural Resources Defense Council, which hired Kimerling as its Latin America Representative.

Knowing she could always come back home, put on a suit and pair of high heels and practice law again, Kimerling put in her notice at work. After spending years of her life looking at disease and contamination caused by toxic substances, she looked forward to spending her days in the beauty of the rainforest. She couldn’t have imagined just how wrong she was. What awaited her was far worse than Love Canal.

In Ecuador, “I Want to See Everything”

On Valentine’s day in 1989, energized with the sense of adventure, Kimerling packed everything she could fit into her suitcases and hopped on a flight from New York City to Quito, Ecuador’s capital city.

She carried one bag filled with books, seeking to learn as much as she could about Ecuador and the rainforest. The geographically diverse Latin American nation straddles the center of the Earth and is home to three diverse ecosystems: the Galapagos Islands and coastal plains in the west, snowcapped Andes mountains in its center, and the upper Amazon basin in the east. In surface area, the nation is smaller than the state of Nevada, but is home to about 8 percent of the Earth’s amphibians, 5 percent of Earth’s reptiles, 8 percent of Earth’s mammals and 16 percent of Earth’s birds. Most of the land that is now Ecuador had been part of the Inca Empire until the Spanish conquest in the 16th century. Politically, until the 1970s, the nation teetered between military dictatorships and civilian control, and has since gone through periods of political instability. Economically, Ecuador had primarily exported commodities like bananas, chocolate and coffee, but since Texaco’s 1967 discovery of oil in the country’s Amazonian region, petroleum has been the nation’s largest export, and the United States its biggest buyer.

Kimerling had read that oil production itself did not cause harm to the rainforest, but that the roads companies built to access wells were the primary sources of environmental damage. Those roads led to colonization and the growth of other industries like agriculture and logging. The information echoed what NRDC had told her about large development projects being an area of concern.

Not one for excesses, Kimerling settled into a sparsely furnished two-bedroom apartment. Though it lacked a TV and refrigerator, she brought with her one indulgence: a digital cassette player and speakers, along with a bundle of mix tapes filled with ‘80s dance music and jazz. At an art gallery opening in Quito, she met an American expat who was working as a consultant for a U.S. oil company. He assured her that the company, too, was upset by how colonists using company roads hurt the forest through road construction. But something about the conversation made her begin questioning the prevailing wisdom that oil operations did not harm the forest.

In May 1989, Kimerling traveled back to Coca, the Amazonian town she had visited before starting law school, and met with the local Kichwa Indigenous organization FCUNAE (Federation of United Communes of the Kichwa Nationality of the Ecuadorian Amazon). Kimerling said she asked the leaders of FCUNAE if oil operations were causing contamination. Initially, the group didn’t know the word “contaminación,” but when Kimerling explained what it meant, recognition instantly flashed across their faces.

The organization’s members showed Kimerling where a ruptured pipeline had spilled nearly 300,000 gallons of oil into the Napo river, turning the water and surrounding soil and plants black, and affecting families living as far into the forest as near the Peruvian border. The spill affected more than 550 families who, among other injuries, lost their gardens—a crucial source of sustenance.

In palm-roofed huts, she sat and listened to people’s experiences of life on the oil frontier. Unlike some of the “greens,” (what her sources called American environmentalists) who occasionally came through Quito, Kimerling gladly visited communities, accepted shared meals and slept on palm-wood floors in her sleeping bag. In a photograph from that time period, Kimerling, with a crop of dark curly hair and a wide smile, is kneeling down in front of a wooden home in the forest. She’s next to a leader of FCUNAE and both she and the man are petting a baby tapir—an Amazonian mammal that looks like a cross between a baby horse and an anteater.

It was during her first trip into the forest that Kimerling, with her notebook and camera in hand, saw her first waste pit. It was one of more than 1,000 that Texaco, operating in a consortium with Ecuador’s state-run oil company, used to dispose of formation water and drilling waste, both hazardous byproducts of oil extraction filled with heavy metals and other toxic chemicals. Even for someone familiar with mass chemical waste, the sites and smells in the forest horrified her.

She thought about how, after Love Canal, American companies knew that they couldn’t just dig a hole in the ground, fill it with waste and walk away. But here, Kimerling had discovered that Texaco, which had marketed itself as using “best international practices,” was doing just that in the middle of the rainforest—back home, some U.S. states had long since outlawed the indiscriminate dumping of drilling waste, and federal law banned the onshore dumping off oilfield wastewater. Locals told her about their afflictions including skin rashes, miscarriages, birth defects and breathing issues. Livestock and animals died prematurely, devastating already impoverished farmers. “I want to see everything,” she told the locals.

Kimerling’s experience working at Love Canal led her to seek out the advice of technical experts to make sense of how the sloppy waste management practices she had witnessed could impact human health and the environment. She tracked down an American living in Ecuador at the time named Mark Cullen, a respected occupational medicine doctor. Soon, Cullen became a go-to resource when Kimerling had technical questions or when she got access to chemical data and wanted to be sure she understood it correctly. Whether because of her disarming southern nature or her genuine desire to understand, government and oil officials voluntarily gave Kimerling information about oil operations otherwise kept from the public. She learned, among other things, what officials knew about the amount of spills and waste discharges, and that oil and drilling waste products like produced water and sludge are highly toxic and can harm aquatic life even at very low concentrations.

Kimerling also got an education in the political and social contexts of the oil patch while heading off to a community protest against Texaco. Kimerling and her companions were stopped at a military camp outside of Coca where officials questioned where the group was headed, then promptly detained them. Kimerling was taken to a jail in Coca, but when officials ordered her into a dank, windowless concrete cell filled with men, she refused to enter. Taking in the cell’s stench of sweat and urine, Kimerling harnessed all of her indignation, declaring: “I’m not going in there.”

She alternately professed her innocence, questioned why she had been detained and demanded to speak with the U.S. Embassy. An officer told her she was being held because she had been talking about contamination. “You should go home and talk about contamination in the United States,” he snapped. She was allowed to stay in the jail’s courtyard, where she sat for hours without food, water or toilet paper, and not knowing what would happen.

Kimerling convinced the officers to release her for the night on the promise that she would stay in a hotel that evening and come back—something that was all but assured as the police had confiscated her passport. The next day, a leader of an Amazonian Indigenous group came to the jail and negotiated Kimerling’s release. She also found out that friends of hers in Quito had also been hounding the U.S. Embassy to intervene.

The experience was the first, but not the last, time Kimerling witnessed first-hand the arbitrary use of power against people who had done nothing wrong.

“Amazon Crude”

Kimerling spent June of 1989 writing a report that would eventually become “Amazon Crude,” a 132-page heavily endnoted tome on Ecuador’s oil industry.

Her writing resonated with locals, but before long, Kimerling became ill. When she went to doctors in Quito, no one could figure out what was wrong with her. Finally, after months of her health deteriorating, a gastrointestinal specialist determined she had a tapeworm and five major parasites, including one linked to the bacterial infection shigella. Kimerling returned to her parents’ home in Birmingham where she was successfully treated. After she recovered, she received stinging news from her contact at NRDC that the organization wasn’t interested in Amazon Crude.

With her illness fresh in her mind, Kimerling doubted whether she should continue living in Ecuador and she returned to Quito to pack up her apartment. That’s when she got a phone call that changed her life.

On the other line was an NRDC official who told her that Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the nephew of the former U.S. president, was leading a “rescue the rainforest” campaign for the organization as its celebrity spokesperson. NRDC asked Kimerling to take Kennedy, then a crusading environmental lawyer, into the forest. In July 1990, she acted as Kennedy’s guide into the Ecuadorian Amazon, taking him and a group from NRDC to see waste pits, local communities and once-pristine forested areas now covered in oil and chemical waste.

Moved by what he saw, Kennedy pushed for NRDC to publish her work and wrote the forward to Amazon Crude. “Like most U.S. citizens, I like to believe that when American companies go abroad, American values go with them. This hasn’t happened in Ecuador. Today, American-owned companies are leaving an ugly legacy of poverty and contamination in one of the most important forests on earth,” he wrote.

Published in 1991, Amazon Crude is an exhaustive account of the environmental and human impacts of every stage of oil operations. Texaco plays a starring role in the book, having dumped at least 3.2 million gallons of toxic produced water per day, flared nearly 50 million cubic feet of noxious gas daily and spilled 17 million gallons of crude from the main pipeline alone in the rainforest during its three decades of Ecuadorian operations, Kimerling found. The company also “set the precedents and standards for oil operations” in the country, since Ecuador lacked the technological know-how—the Andean nation’s lead export, Kimerling wrote, had been bananas before Texaco struck oil in 1967.

Her photos depicted an apocalyptic scene: plumes of black smoke emanating from torched waste, pits filled with thick black gunk across decimated landscapes and pipes spewing toxic sludge into waterways.

Kimerling’s sharp economic analysis concluded that, despite early promises that the discovery of oil would transform Ecuador’s economy, the country remained hooked on oil and burdened by large amounts of foreign debt—insights that remain true today.

The toll and rapid changes that oil operations thrust upon Indigenous communities were emphasized heavily throughout the book. In a highlighted section entitled “The Tagaeri, The Last Uncontacted People of the Oriente,” Kimerling wrote about the 1987 killing of two Capuchin missionaries, Bishop Alejandro Labacoa and Sister Ines Arango, who had sought to de-escalate tensions between the Tagaeri (coincidentally, the family of the uncontacted girl, Conta, who would much later become Kimerling’s client) and oil companies seeking to expel them from Tagaeri ancestral lands rich in oil. Labacoa and Arango had been pinned to the forest floor with multiple spears and their deaths had attracted international attention at the time. Kimerling wrote that the killing of the missionaries overshadowed an attempt by oil companies to use armed mercenaries to murder the Tagaeri who stood in the way of oil operations. It is widely believed that the Tagaeri’s leader, Taga, was killed by oil workers.

Kimerling’s book sent ripples throughout the country and region. In a Quito-based newspaper, a leading columnist questioned why it had taken a North American to publicize what was happening in Ecuador. Kimerling received so many threats in the wake of the book’s publication that U.S. embassy officials intervened and introduced her to Ecuadorian officials. The reaction of Texaco and its consortium partner, the state-run oil company Petroecuador, were swift. Texaco denied wrongdoing and defended itself on the basis that it hadn’t violated any Ecuadorian laws—the country at the time had virtually no environmental regulations. Kimerling questioned this, recalling from her Yale torts class that the first source of environmental law didn’t come from regulations but from the common law. She then read, cover to cover, the entire Ecuadorian civil code, confirming that there were nuisance and other laws that the company had seemingly violated. It’s just that no one had enforced them.

Back in the United States, her work inspired Congressional legislation entitled the “Pan-American Cultural Survival Act,” aimed at assisting Indigenous peoples throughout the Americas to protect their lands and the environment, as well as the “political empowerment” of Indigenous peoples. During a March 21,1991 hearing, Sen. Alan Cranston (D.-Calif.) likened America’s treatment of Native Americans to the current situation of Latin America’s Indigenous peoples. Citing Kimerling’s work, the senator highlighted the oil industry’s “grave threat” to the “physical and cultural survival” of Ecuador’s Indigenous peoples. “We are linked, as fellow humans, to the fate of Indigenous peoples because the areas in which many of them live—the rainforests of Central and South America—are vital sources of oxygen and a biological diversity, the importance of which modern science is only beginning to understand,” Cranston said at the hearing.

Another American oil company operating in Ecuador put pressure on the then-U.S. ambassador to Ecuador, Paul Lambert, to publicly extol the importance of oil development to U.S.-Ecuador relations. But after meeting with Kimerling and others, Lambert decided to visit the forest. By that time, Texaco had turned over control of operations to Petroecuador. Following Lambert’s visit, a cable was sent from the American Embassy in Quito to President George Bush and his secretary of state:

“By most accounts, Petroecuador’s treatment of the environment is the worst of all the oil companies in Ecuador. In part this is because it inherited from Texaco established fields where the existing equipment and procedures do not reflect current industry practices.”

Kimerling’s research prompted U.S. oil companies to start rhetorically distinguishing themselves from Texaco and make the claim that they could extract oil from the forest in an “environmentally friendly way that benefited local communities.”

She wondered: Could it be possible?

“You Don’t Want Me as Your Enemy”

Around the time Kimerling was writing Amazon Crude, the U.S. oil company Conoco discovered commercial quantities of crude inside previously undeveloped areas of the rainforest known as Oil Block 16. That oil sat underneath the ancestral territories of some Indigenous Waorani family groups, the most recently contacted of Ecuador’s Indigenous peoples, who had been entirely cut out of the Ecuadorian government’s decision to allow Conoco to explore for oil in the area.

Kimerling had worked on a January 1990 letter sent to the World Bank and Ecuadorian government that included a demand that Indigenous groups be given legal title to their lands and that ongoing oil operations, like Conoco’s, stop unless and until their consent is obtained. NRDC had asked Kimerling to write the letter, and she used the opportunity to bring together environmental and Indigenous groups to draft it.

And so she was surprised to receive a call from Kennedy, asking her to negotiate a deal with Conoco officials and sell it to groups in Ecuador. According to Kimerling, Kennedy explained that oil drilling would go forward with or without Conoco as the operator, and since Conoco promised its operations would be environmentally friendly and benefit locals, Kimerling should use her influence to persuade the coalition that had signed the World Bank letter to back down from their opposition to drilling. Kimerling got the impression that Kennedy felt he knew what was best for Waorani groups despite knowing almost nothing about them.

She refused to give in, believing that the decision of whether to negotiate with an oil company or resist should be made in Ecuador and not by her or NRDC. This got her fired from NRDC, and it was not an amicable parting, she said. The organization tried to get her to sign a nondisparagement agreement barring her from criticizing NRDC or Kennedy, and attempted to seize control over the copyright ownership of Amazon Crude, which was in the midst of the publication process. She refused to sign the agreement and left the NRDC office in New York feeling as though the nonprofit had taken everything from her but her dignity.

She made phone calls to her Ecuadorian contacts to apologize and explain what had happened. She told the groups that they would have to decide whether to work with NRDC and Conoco. As Kimerling recalled, Kennedy’s last words to her before she was fired were: “You don’t want me as your enemy.”

In an interview last week, Kennedy denied saying that to Kimerling and told me that in negotiating with Conoco, he was acting in his capacity as an attorney and on behalf of his own Indigenous clients who had an interest in stopping colonists from appropriating their land. Conoco had promised to prevent that, he said. Kennedy called Kimerling a great advocate, said he has “nothing but admiration for her.”

In 1992, Conoco pulled out of Ecuador, and a U.S.-based oil company, Maxus, took over in Block 16, opening up a new oil front in Waorani territories. Conoco did eventually operate in the Ecuadorian Amazon through its subsidiary, Burlington Resources, from 2006 to 2009, leaving behind $95 million in environmental damage in areas that included ancestral Tagaeri land, according to an international arbitration tribunal.

Evangelizing—and Ethnocide

Kimerling entered a period of uncertainty after her parting from NRDC. It had been disappointing to see an organization she respected make what was in her view a deeply flawed decision. She came to see the event as part of a larger problem plaguing some nonprofits. In her telling, those organizations do some important work, but their need for fundraising and self promotion can distort their priorities. Kimerling told me some organizations “think they know what’s best and make decisions that are disconnected from the desires of grassroots communities even when they claim to speak in the communities’ names.”

She resolved never to be beholden to outside interests and decided the best way to do that was to work independently, even if that meant living off of her savings for a period of time. She returned to Ecuador where she partnered with an Indigenous organization to publish a Spanish version of Amazon Crude. In 1993 “Crudo Amazónico” was released and copies of the book made it to rainforest communities as far as across the Peruvian border. Because Kimerling had insisted that photos and graphics be used to help tell the story, non-Spanish speakers could understand its essence.

Kimerling personally delivered a copy of the book to a remote village known as Bameno (Bah-Meh-No), home to a Waorani family group, the Baihuaeri (Bai-Wade-eee). Kimerling learned that unlike some other Indigenous peoples, the Waorani did not identify as one nationality but rather are a constellation of independent hunter-gatherer family groups known for their fierce resistance to outsiders, vast knowledge of the forest and unique Wao-terero language. Using their signature hardwood spears, they had resisted attempts from rubber tappers and Spanish colonizers to conquer and contact them. Three groups, known as the Tagaeri, Taromenane and Dugakeri, are widely believed to be the last three remaining “uncontacted” Waorani groups.

Kimerling embarked on her two-day journey to Bameno from Coca by first traveling down the Via Auca, a 60-mile Texaco-built and named road that ran southward from the city. The road, rimmed with pipelines, gas flares and oil production sites, sliced through ancestral Waorani lands, including territory once belonging to the Tagaeri but that now was overrun with colonization. Once the Via Auca ended near the shore of the Shiripuno river, Kimerling traveled by motorized canoe down the meandering Shiripuno, and then the Cononaco River, until she reached Bameno.

There, Kimerling met Penti Baihua, a young father who by virtue of his ability to speak Spanish had become an intermediary between his Baihuaeri clan and the outside world. Penti, with long soft ink-colored hair, gentle eyes and a stoic demeanor, welcomed Kimerling to the village, a collection of homes made from thatched palm leafs and organized around a small landing strip carved into the forest by an oil company. Over three decades, he would become her most important Waorani guide and mentor (and, much later, one of the witnesses she called to testify before the Inter-American court).

As a young boy, Penti had lived freely in the forest until he was around the age of 6 or 7, when American missionaries with the Summer Institute of Linguistics forced contact on some members of his Baihuaeri family.

All Waorani peoples had lived isolated in the Ecuadorian Amazon region until 1958 when those missionaries began the first wave of a campaign called “Operation Auca,” aimed at contacting and evangelizing the Waorani. The term Auca is a pejorative term meaning “savages.”

The second wave of that campaign took off in the 1970s when Texaco encouraged and helped the missionaries to accelerate and expand their campaign into areas where the company wanted to operate. The aim was to clear Waorani people from their land, sever their relationship to it and change their culture so drilling could move forward. “The aim was ethnocidal,” Kimerling told me.

The missionaries took the Waorani they contacted, including Penti, to a settlement known as Toñampare. There, polio and other diseases broke out, killing and handicapping dozens of Waorani people. The missionaries told the surviving men, women and children that their culture was sinful and the Bible offered salvation.

The Baihuaeri had been one of the last family groups contacted by “Operation Auca.” Some of the Baihuaeri had gone to live in the Toñampare settlement, and later returned to their ancestral lands while others never left the territory at all. Bameno evolved into the Baihuaeri’s permanent settlement deep in the rainforest, though its residents still hew to their ancestral semi-nomadic ways of living by traveling throughout their territories to hunt, gather, plant and live. As a teenager, Penti left Toñampare and returned to the Baihuaeri’s ancestral territory.

Kimerling’s brief encounter with Penti left her with a sense that there was something special about him. She had seen and heard how some oil companies were trying to corrupt other young leaders and she heard stories about how oil workers sometimes took Waorani men to brothels and introduced them to alcohol. Kimerling suspected that Penti was different, but as she bid goodbye, she wasn’t sure if she would ever see him again.

“Information is Power”

Amazon Crude attracted the attention of Cristobol Bonifaz, an Ecuadorian expat, lawyer and chemical engineer living in Massachusetts. The book inspired him to assemble a team of lawyers to file a class-action lawsuit against Texaco in the United States on behalf of about 30,000 colonists and Indigenous people affected by the company’s operations. In October 1992, Bonifaz wrote to Kimerling, asking her to join his team of lawyers.

While Kimerling considered the offer, friends of hers in Ecuador informed her that Bonifaz’s lawyers, while trying to sign up plaintiffs, had said Kimerling was working with the team. The news troubled her. Kimerling wanted to see the company held legally accountable for what it had done, but felt the lawyers were trading on her good reputation and weren’t being truthful. She declined Bonifaz’s offer.

In November 1993, she was at the Coca headquarters of FCUNAE when someone handed her a copy of a New York Times article. Splashed across the paper was the headline: “Ecuadorian Indians Suing Texaco.” Though she knew it was coming, the news still sent a shockwave through her body. The lawsuit, she said, resonated with locals because it echoed their grievances but people began asking her “Why do strangers speak in our name without authorization, without even telling us?”

Kimerling closely followed the developments in the Texaco case as the litigation played out in New York, but the crux of her work throughout the 1990s and beyond remained focused on what was happening on the ground in Ecuador. Foreign oil companies, including U.S. based Maxus, Murphy Oil and Occidental Petroleum, were expanding their operations, affecting more and more people and parts of the rainforest. Amazon Crude had prompted a rhetorical shift among those companies and Kimerling began to hone in on it.

Locals informed her that when they complained to officials about contamination, companies rebuffed the allegations by declaring that they use “cutting edge technology” and abide by “international standards.” Kimerling was well steeped in international, Ecuadorian and U.S. environmental laws, and so the phrases spurred her to start asking questions because as far as she knew they had no real meaning. She wanted to find out what they meant and how they affected governmental actions.

She focused her research on the U.S. multinational Occidental Petroleum—the same company she had squared off against over hazardous waste at Love Canal. Now, Occidental had announced a “sustainable development” initiative to benefit local Indigenous communities. In what Kimerling dubbed the company’s “glossy brochures,” Occidental vowed it would operate in an environmentally responsible manner. In six law review articles and a Spanish language book titled “Model or Myth? Cutting-edge Technology and International Standards in the Occidental Oil Fields,” Kimerling concluded the company’s promises were more myth than model.

Her topline finding was that the promise of “international standards” had led to Ecuador effectively outsourcing environmental governance to private companies that policed themselves without any independent verification or monitoring. Companies, in one of the first instances of greenwashing, used the authoritative sounding phrase to placate locals and allay government officials’ concerns while privatizing environmental regulation. Her meticulous research revealed that often the devil was in the details. Buried within hundreds of pages of regulatory documents were permissive phrases, like companies “should” endeavor to use best available practices, rather than including binding requirements.

“Corporations were saying we’ll voluntarily raise standards beyond what’s required by national law and it gave government officials and the public a false sense of complacency when it wasn’t true,” Kimerling told me about her research.

As she was carrying out that investigation, local Indigenous groups organized workshops for her to share her findings. Kimerling, propelled by the maxim that information is power, brought with her stacks of spiral bound packets, what she called her “book of sources,” to distribute at the meetings. The packets contained copies of the Ecuadorian constitution, Occidental’s Environmental Management Plan and other information from her research.

Nowhere was the adage, that information is power, proving to be more true than in the unfolding Texaco litigation. After Bonifaz filed the case in New York City, Texaco initiated closed-door settlement negotiations with the Ecuadorian government over how to resolve its responsibility for the contamination it had caused there. The company agreed to conduct limited remediation of some of its operating sites, with Texaco’s consortium partner, the state-owned oil company, agreeing to take responsibility for the remaining sites. It was an audacious legal maneuver by Texaco—the agreement was forged between two parties that had been responsible for the pollution, as well as the forced contact and displacement of Indigenous groups.

To try to get access to information from Texaco, Kimerling bought one share of the company’s stock and attended an annual shareholder meeting. There, she spoke out about what she said was the speciousness of the cleanup effort. The company’s then-general counsel, Deval L. Patrick (who subsequently became the governor of Massachusetts), approached Kimerling after the meeting and told her he was surprised at what she said because Texaco’s consultants had verified the cleanup. He offered to give her a copy of the consultants’ technical remediation report. Kimerling, with the help of an independent chemist, scrutinized the document, concluding the cleanup was mostly “cosmetic.” She also reviewed settlement documents and recognized the name of the Ecuadorian environmental authority who had signed off on the agreement; he had worked for the state oil company at the same time.

Meanwhile, Texaco pushed to have Bonifaz’s class action lawsuit dismissed and moved to Ecuador, proclaiming that corruption was not a problem there and that the Ecuadorian justice system had strong rule of law.

In 2002, a federal judge in New York, Jed Rakoff, dismissed the lawsuit, ruling that Ecuador was the more appropriate forum to try the case and declaring that the dispute “has nothing to do with the United States.”

Back to Quito

Watching Kimerling sort through the contents of her storage locker in Quito, I pointed out that she had amassed a large pile almost entirely composed of documents related to the Texaco case. Looking over at them, the corners of her mouth turned downwards and she frowned.

For Kimerling, and other legal experts I talked with, Judge Rakoff’s decision was the coup de grâce of the Texaco litigation—it was, they told me, futile to try to successfully sue Texaco in Ecuador at the time given the oil industry’s power there, and rampant corruption within the country’s judicial system.

The decision was in line with a larger U.S. Supreme Court shift in jurisprudence that has made it virtually impossible for foreigners to sue American companies in U.S. courts for harm those companies cause abroad.

Kimerling, aghast at the decision, wrote a 252-page law review article with more than 600 footnotes challenging Judge Rakoff’s reasoning that the case had nothing to do with the United States. In her analysis, she pointed out that the judge had accepted Texaco’s post-litigation portrait of itself as merely a contractor of the state. In a chapter entitled “The Two Faces of Texaco,” Kimerling cited Texaco’s own documents, advertisements and officials’ statements casting itself as a world-class company that was teaching the Ecuadorians the business of oil. There was also the fact that Texaco was the sole operator of the Ecuadorian oil fields until 1990.

For a while, she had believed that if the company’s behavior was made public, Texaco officials would be pressured and shamed into redressing the suffering it had caused. But this did not happen. That lack of accountability and the expansion of the oil industry has rippled throughout the region and across time, the violent consequences of which Kimerling would come to confront over the next two decades.

Coming tomorrow in Part 2 of The Education of Judith Kimerling: After violence erupts in the Amazon, Kimerling begins representing a formerly uncontacted girl in what will become the first case before an international court of law involving the rights of uncontacted peoples.