Harm City: Fifth in a series about environmental justice and climate adaptation in Baltimore’s neighborhoods.

For Ben Zaitchik, the moment had arrived. He’d been working at Johns Hopkins University for almost two years on a groundbreaking effort funded by the U.S. Department of Energy to define what it would take to make Baltimore climate adaptive, resilient and just.

Now, he paced nervously in a spacious corridor at Morgan State University’s Center for Built Environment and Infrastructure Studies, not far from Johns Hopkins’ main campus, making sure that everything was in order for the focus group meeting he had been planning for weeks. The topic: the urban heat island effect, his research specialty.

The 30-odd invitees—a diverse group of neighborhood activists, academics and city officials —were members of Zaitchik’s Baltimore Social-Environmental Collaborative, or BSEC for short. The group was his mechanism for putting neighborhood concerns at the heart of the five-year, $25 million project that was primarily a scientific endeavor, driven by data in four key areas related to climate change—urban heat, flooding, air pollution and decarbonization.

Everyone who’d gathered sat in groups of five and six around tables in a brightly lit conference room, laptops open and the room abuzz with chatter. Margaret Griffin, a Black woman in her 70s, sat at one table, mingling with other participants and ready to share what intensifying heat could mean for people her age and what could be done about the deadly problem.

She’d been invited by Dr. Doris Minor-Terrell, president and CEO of the Broadway East Community Association, who had helped Zaitchik plan the evening.

BSEC was approaching the end of its first year, one that was spent building relationships and installing climate-monitoring technology in up to 30 neighborhoods across the city. The time had finally come for BSEC’s first brainstorming session on solutions in response to the data.

Baltimore was chosen by the federal government, along with Chicago and Port Arthur-Beaumont, Texas, because, like other mid-sized Eastern and Midwestern cities, it has many climate-related challenges—urban sprawl, clusters of heat-trapping surfaces and structures, elevated risks from flooding and heat, and unequal burdens of air and water pollution. City officials hope the effort will guide implementation of Baltimore’s climate action plan, which calls for the city to be carbon neutral by 2045.

“Today,” Zaitchik said as the room quieted down on an early October evening, “we are going to focus on extreme heat. It’s one of those climate hazards that we don’t need a lot of Ph.D.s to tell us is a problem.”

So, Zaitchik continued, he wanted everyone to break into three subgroups for an hour to talk about the heat problem and what might be done about it—cooling centers, mobile clinics, better awareness, more trees, less asphalt, whatever.

Zaitchik, a Boston native who got his Ph.D. at Yale, moderated one of the subgroups, and Minor-Terrell took another. And after lively discussions took off, Minor-Terrell couldn’t help but overhear Zaitchik talking candidly about Johns Hopkins’ complicated relationship with the Baltimore communities it serves, as the city’s largest employer with the world-famous medical center.

“There’s a history of neglect and exclusion of local communities and sometimes of a sense of exploitation for research, cheap labor, etc.,” Zaitchik said, noting that even the expansion of Hopkins’ campus in East Baltimore had changed the neighborhood.

“The university has tried to improve its record in recent years and BSEC benefits from Hopkins’ newfound sense of local purpose,” Zaitchik said, using the acronym for his Social-Environmental Collaborative. “We also contend with hard feelings from the past and from present-day friction that occurs when a large, wealthy institution like Hopkins throws its weight around the city.”

Partnering with Morgan State and the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) in the climate project, along with BSEC, he said, was important in providing a greater foundation for trust.

Minor-Terrell nodded in agreement, feeling Hopkins as an institution was self-centered and motivated by its own research interests. “It doesn’t have the best reputation in terms of how it engages in communities,” she said.

It wouldn’t be enough for BSEC and Hopkins to just share data on climate change with the partnering communities. She wanted them to share data, results and solutions. “I am hopeful that BSEC will lean heavily on community engagement, educating communities around what a discovery is across different fields,” she said.

The hour went by swiftly and the participants regrouped to share their recommendations, which were read out loud. Among them: setting up more sheltering places for people to cool down, water stations, sprinklers in places where people tend to congregate and better civic engagement by city departments to keep residents abreast of severe weather conditions, such as heat waves.

Zaitchik was pleased. “We just need to figure out how we get to the point where we’re not just collecting data but having the communities understand the problem and why we’re there,” he said, echoing Minor-Terrell’s sentiment. “I keep reminding myself that this is a research project. And even though so much of our time is spent working with the communities, understanding their needs, trying to meet their priorities, ultimately, we’re supposed to understand the climate system. So, I think it is a great opportunity, and also a challenge for us.”

In Margaret Griffin’s Neighborhood, a Weather Station

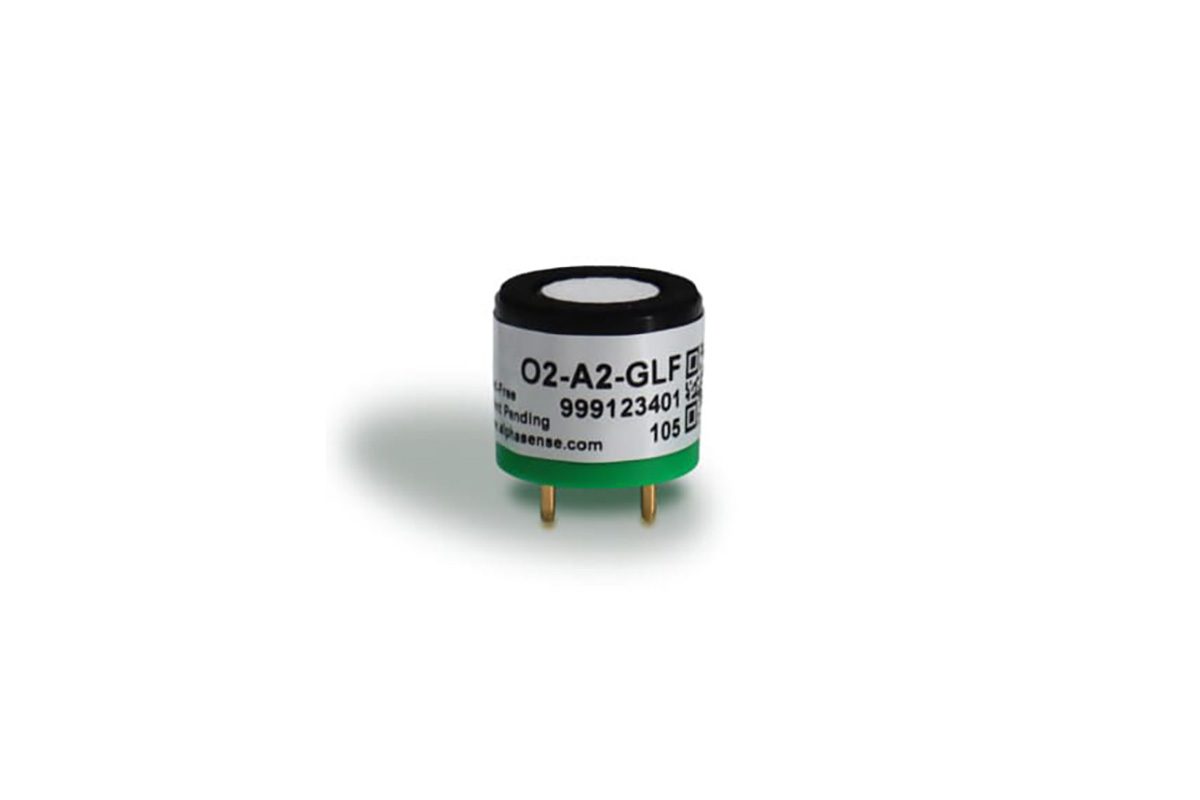

A week later, Zaitchik, 46, rode his bike to a grassy plot at the corner of North Chester and Jefferson Streets in East Baltimore, surrounded by a chain link fence. Tall and fit, with short dark hair around a balding pate and a thin, slightly scruffy beard, he’d come to watch three colleagues install a pre-assembled weather station fitted with sensors that measure precipitation, wind, temperature and solar radiation and that sends the data in real time through cellular systems to computers at Hopkins for analysis and atmospheric modeling.

Margaret Griffin, who lived next door to the plot and had attended the brainstorming session he’d led at Morgan State, looked on from outside the fence. Zaitchik had invited her to the installation.

“If you can capture information about the heat and all of that, and find ways to kind of cool it down, I’m all for it,” she told him in almost a whisper on a hot afternoon in early October.

Zaitchik, a professor and climate scientist in Hopkins’ Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, hopes the weather instruments in 30 Baltimore neighborhoods will allow a team of 80 researchers, including scientists from Pennsylvania State University and other collaborating institutions, to quantify how, for instance, the temperature varies between areas with little tree canopy and those with better tree cover and more green spaces. The data should help create more precise models applicable to other cities with similar urban features, he hopes.

Griffin’s tulips had provided her with another data point of sorts: “Tulips usually come up in the spring,” she said. “But because the weather was so warm this year, they came up super early and some of them didn’t even bloom. And the ones that did, maybe lasted just a day and just died out.”

Now, every time she steps out for a walk or comes back after grocery shopping at the nearby market, she’s greeted rudely by the blackish mulch and dried remains of plants in a wooden stand by the entrance to her home, where tulips and lilies used to be a fixture.

However, dead and wilted plants weren’t the only source of Griffin’s grief. It was also the uncertainty over what weather extremes like intense heat waves would mean for elderly city residents such as herself.

“Right now, it should be cooler I think,” Griffin told Zaitchik. “Today is supposed to be like above 80 or something. Normally, this time of the year it’s nice weather and putting on a ceiling fan works just fine. But today, I walked up the street and by the time I came back I was really warm. So, yes, I’ve noticed the change.”

She looked over and half-gestured towards the Hopkins scientists, their foreheads dotted with beads of sweat, as they wrestled with the weather-measuring contraption, almost 6 feet high. “I think people are becoming more and more aware of climate change and are getting worried about the melting of, like, the ice caps and everything breaking away and just floating out,” she said. “So I think that’s a big concern for some of us: What this all means, and where’s it headed.”

Zaitchik, who started his career studying hurricane-induced landslides in the Middle East, could relate. When he’d finished chatting with Griffin, he got on his bike, with the instrument secured and locked inside the fence.

“There’s no denying that Baltimore is a place with serious challenges and inequities,” he said. “But it’s also a place with remarkable local pride and power to change things for the better. What’s the point in putting in place a state-of-the-art measurement and modeling system unless it’s responding to the needs of the community and the city?”

A Site Visit to Broadway East

Several days later, Zaitchik walked along North Broadway on a BSEC site visit organized by Minor-Terrell of her neighborhood, called Broadway East.

About a dozen participants had begun two miles away in the Old Goucher neighborhood, a dynamic, up-and-coming community that had witnessed an economic rebirth in recent years.

Zaitchik noted that it coincided with grassroots efforts by a few local residents to substantially increase the number of trees in and around the community.

The contrast Minor-Terrell was trying to showcase was evident in the stark, concrete expanse. Not only were there almost no trees, but two shiny black above-ground sewer pipes snaked along North Broadway, zig-zagging through the residential area for miles.

These sewer lines have been here for at least three years, Minor-Terrell told the group, as concerned looks spread across their faces. The residents are heavily affected by the noxious fumes, she said.

Seeing layers of poverty, crime, disinvestment and environmental pollution feeding into one another, Minor-Terrell originally reached out to another Hopkins professor almost two years ago. He ultimately introduced her to Zaitchik, which led to her role in BSEC. Now, hardly a week passes without them working together on ways to find solutions to the problems faced by the neighborhood, and to make BSEC more community-facing.

“It’s not like we just made this up,” she said, shepherding the group through East Broadway streets. “It’s everyday life for people living in certain pockets of the city, so close to Hopkins. I would hope that somebody would say, ‘How is this possible that one half of the city was like 40 percent green and another neighborhood only has 7 percent tree cover?’”

Not having access to tree cover is a form of discrimination that affects the air quality and heat index of communities, she said. According to the American Forest database, tree canopies are unequally distributed across Baltimore, with tree coverage in areas such as Broadway East, Pigtown and Franklin Square nearly 60 percent lower than in wealthier areas of the city, like Federal Hill and Roland Park.

A 2022 research paper by three U.S. Forest Service scientists found that areas with lower incomes or more racial minorities tend to have less tree cover, and that 94 percent of formerly redlined areas they studied had “elevated temperatures relative to their non-redlined neighbors” by up to 7 degrees Celsius.

“On average, land surface temperatures in redlined areas were approximately 2.6 degrees [Celsius] C warmer than in non-redlined areas,” the scientists wrote.

In Baltimore, 86,000 people live in neighborhoods like Baltimore East that were 10 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than others with more tree cover, like Old Goucher, according to a report by Climate Central.

The nonprofit found that Baltimore is one of only 12 cities with temperature increases in some neighborhoods of more than 12 degrees because of sparse tree cover and vast impervious surfaces made of asphalt, steel and concrete that absorb and retain daytime heat.

Zaitchik, an expert in urban heat, said research clearly showed that historically redlined neighborhoods where housing discrimination once occurred were considerably hotter than white, affluent communities, and that people with underlying conditions were at a greater risk.

The challenge to protect city residents and the vulnerable populations would only grow, Zaitchik said, because stressors like climate change were super-charging extreme events such as heat waves and the urban heat island effect.

Old Goucher’s experience with tree planting had inspired Minor-Terrell, and leaders from the two neighborhoods have been working together over the past several years. “These two communities really helped inspire the concept of BSEC,” Zaitchik said, as he walked to keep up with the group on North Broadway.

Both neighborhoods are now partnering with BSEC and have separately formed a city-wide coalition of six communities called the Baltimore Climate Resilience Coalition. Drawing from past experiences, the coalition aims to turn the participating neighborhoods into green, pedestrian-friendly communities.

Unlike the focus group session at Morgan State, Zaitchik mostly stayed in the background during the site visit, listening to the group conversations and, from time to time, chiming in on ways the partnership between BSEC and its community partners would benefit the city.

“I was taking a backseat because I wanted to emphasize local leadership. We want to show that they are the ones driving the change. It’s not about us,” he said, describing how he learned something new and profound every time he talked with community leaders like Minor-Terrell.

“They have such deep knowledge of the place, which is fundamental to BSEC, because for knowledge to be actionable and equitable, it needs to be place-based.”

Annual Meeting

In early November, back at Morgan State, Zaitchik faced another defining moment as BSEC’s members gathered for their first annual meeting: showcasing the group’s achievements. He sat, legs crossed, in one of the front rows of the Engineering School’s spacious auditorium. Minor-Terrell sat toward the back, with the fellow advocates from Old Goucher.

Zaitchik explained that the session would begin with eight presentations on climate science covering heat, greenhouse gasses, atmospheric dynamics, air quality, water, vegetation and soil health, decision science, and buildings and transportation. Then, the focus would shift to adaptation and mitigation strategies evolving in partnering communities.

“We have the basic science teams organized according to the way that we think about the physical environment, air quality, atmospheric dynamics, water, vegetation, things like that. And what they’re trying to do is define the science questions and the methods to address questions within discipline,” Zaitchik said.

They would address the four cross-cutting issues related to climate change—urban heat, flooding, air pollution and decarbonization. And so the presentations began, as a parade of researchers described their targets, the data they were gathering and the adaptation strategies that might emerge.

Climate change would likely modify air pollution exposure in the coming years, one member of the air quality team said, explaining how its findings would focus on that interaction and what to do to reduce human exposure to hazardous particles in the air.

The atmospheric dynamics group explained how team members were attempting to understand and model the variations of weather within Baltimore and how the urban environment interacted with weather conditions. That was critical for designing equitable strategies to mitigate urban heat, flooding and air quality, as well as prevent hospitalizations related to heat exposure and asthma in Baltimore’s vulnerable neighborhoods.

After the science presentations, some activists in the room made it clear that they wanted to hear more about how the project would address the real issues faced by their communities. “My question is for the vegetation and soil health team,” one said bluntly. “There’s already enough data out there about soil health in Baltimore. What I want to know is when will you come up with solutions to the problems that we already know enough about?”

The question echoed a recurring theme throughout the session: when do data-gathering and modeling end and solutions begin?

Zaitchik, for one, recognized the tension between the research focus of the project and expectations that come with engaging communities.

“Questions like these help to keep our feet to the fire,” Zaitchik said.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

Another complication: the $25 million climate adaptation project that Zaitchik was helping lead wouldn’t fund those neighborhood solutions. Which was why, Zaitchik explained, he was starting to help BSEC partners write grants and other proposals to secure the money they needed for things like tree planting, cooling centers and storm-related infrastructure to protect against flooding.

Minor-Terrell chimed in that it’s always challenging to get city administrations to invest in public health and infrastructure. But she is hopeful that the data being gathered would demonstrate to city managers that communities like Broadway East can benefit from equitable climate solutions.

“I can’t afford not to have hope,” she said. “If I don’t have hope, it means to me that there’s no pathway to the future for my people who live in marginalized communities.”

Her priorities in Broadway East, she said, were basic: She wanted to help families to breathe better air, get some kind of relief from excessive heat, and rid their basements of mold.

The most important accomplishment in the first year of BSEC, Zaitchik said, was establishing these relationships—with understanding of each other as a team.

“From a scientific perspective in year one, getting the instrumentation out with all the supply chain constraints and permitting requirements was huge,” he said. “And bringing in a team of researchers and students, that was big. But in year two, we really need to focus on solutions.”

If BSEC’s data could help communities make the case for needed funding, he said, that would also be huge.

“I would like to see a situation where there is funding delivered for, let’s say, the Broadway East greening initiative, and knowing that that funding was unlocked in some part thanks to our ability to document the benefits of increasing tree canopy in the neighborhood,” Zaitchik said. “If we can demonstrate that a city like Baltimore can adopt equitable mitigation pathways as a result of our efforts, then that would be the ultimate success for us.”