As the director of Creation Care Alliance of Western North Carolina, Sarah Ogletree has spent the last three and a half years working from her base in Mitchell County to empower congregations and interfaith organizations in the fight for climate and environmental justice.

She and other faith leaders active in the climate movement have long believed faith and faith organizations can be a powerful force for climate action, but since Hurricane Helene devastated her community, she has a whole new appreciation for just how central faith organizations are to disaster recovery.

Tallessyn Z. Grenfell-Lee, a scientist, theologian and climate activist, speaks of the need to foster hope in the face of future climate uncertainty.

Rosie Alegado, a native Hawaiian scientist who studies Indigenous seascapes at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, sees her community’s spiritual and cultural traditions are critical in helping Indigenous peoples cope with a very uncertain future.

And Heather McTeer Toney, a former mayor in Mississippi turned environmental justice activist, says her Pentecostal faith has enabled her to reject “dominionism” and embrace the fight over climate change as a duty to care for one another.

Beyond the tangible aid work at Creation Care Alliance, an interfaith nonprofit based in Asheville, N.C., Ogletree, 32, herself Christian, has witnessed how faith leaders are stepping in to help a community overwhelmed by collective grief.

Many people are still missing, and at this point, presumed dead. In the absence of a body, survivors have been left in limbo, with none of the familiar mourning rituals available to navigate their grief.

“I think there’s a real place for leaders that are familiar with gathering people and helping lead them through ritual, to step up right now and help people process,” said Ogletree.

“And a lot of my work over the past 10 years has been focused in climate resilience and community hub building, focused within congregational spaces and also support for eco grief. All of these things have just like really, really, come home to roost in the past couple of weeks,” said Ogletree. “I kind of anticipated [something like] this would happen eventually, but I also didn’t anticipate it would happen this soon. It’s been really jarring.”

Her days are now spent coordinating sleeping arrangements for church volunteer groups, connecting people who lost houses, family and jobs with desperately needed resources, and distributing heating supplies as temperatures dip to dangerous lows as thousands remain in tents, cars and shells of homes gutted by floodwater.

Since the storm, Ogletree has had to reckon with the incalculable scope of loss that comes with living in the era of climate change. She has made peace with the realities of the anthropocene in her own life, but still struggles with what it will mean for her daughter’s future.

“I have this amazing kid… and then I’m holding her, watching my whole world get rocked outside. And, you know, watching tornadoes in a river and things washing away. And she’s a year and a half old, and I’m like, my God, you know, I thought we had more time. I didn’t think she would be a baby in her first severe climate impact,” said Ogletree.

Given the amount of work she has already done around climate grief and hope in the face of loss, Ogletree has been able to find her equilibrium even when staring down a future where bad outcomes are plentiful and certainty is a luxury of the past. “For a long time, I was living with this idea that there would either be a full climate apocalypse or it would be a technocratic utopia, and there wouldn’t be any in between,” said Ogletree.

It is only through processing her grief that she has come to realize, “in life, it’s very rare that things are either terrible or beautiful. Usually, there is a lot of both all tumbled together by the act of living.”

Though she isn’t certain what the future holds, Ogletree is grateful to have her daughter and finds strength through her faith.“Who am I to say what makes life worth living? And who am I to say that there won’t be beauty?” said Ogletree. “Things are terrible and beautiful. There’s grief and there’s joy, and those things are connected, and I don’t think we can experience one without the other.”

Climate Change’s “Attached Hope” Problem

Tallessyn Z. Grenfell-Lee, 50, a consultant on ethical leadership in the era of climate change, calls that kind of conviction to living and working for the good of others and the planet “unshakable hope,” and she sees it as vital for maintaining a sense of purpose as climate change continues to worsen.

Grenfell-Lee wasn’t always a theologian and ethics consultant. She spent many years as a biotech researcher at Harvard and MIT. During that time, she found that her colleagues, particularly those focused on climate change, were wrestling with how to both deal with the psychological implications of what they were finding, and how to effectively communicate about climate change with the public without making people so scared they shut down.

Grenfell-Lee has always felt deeply connected to her faith, coming from generations of clergy and theologians. During her time in academia, she found that faith was broadly a taboo subject. When she saw that her colleagues didn’t have a framework for discussions around ethics and doubt that so often come up in the context of climate change, Grenfell-Lee decided to go back to school to get a doctorate in social, environmental and theological ethics, where she focused on the ecological ethics, and what she calls climate change’s “attached hope” problem.

Many people define hope as the desire for a specific event or outcome, said Grenfell-Lee, who calls this type of hope “attached hope.” But if all you have is attached hope, and the outcome you wanted doesn’t happen, it can feel like everything you did was for nothing, she explained.

“The thing a lot of people don’t realize is that there’s another definition of hope. And it’s an ancient definition. It’s a hopefulness that is about doing the right thing, no matter what happens. That’s our non-attached hope,” said Grenfell-Lee. “I call it unshakable hope. And that’s the kind of hopefulness that we need. We need a hopefulness that is bigger than an outcome.”

Grenfell-Lee’s faith is central to her unshakable hope, but she is quick to point out that religion isn’t a requirement for cultivating non-attached hope; it is just the framework she uses. People just need better stories. “Storytelling is as old as being human. And the stories we tell ourselves about situations dramatically affect whether we approach the day from a place of scarcity and fatigue, or from a place of boundless joy,” said Grenfell-Lee.

The kind of stories she is talking about are often cultural touchstones. “In every culture throughout history, when people have faced down the worst possible things, these ideas have arisen in the human spirit that we can sing in the face of death,” she said. “You’ve got story after story about this. And it’s not disrespectful of suffering, it’s the opposite. It’s a triumph of life and the human spirit over anything.”

The problem, said Grenfell-Lee is that they often aren’t the narrative we are taught to picture ourselves in. She is not talking about narratives that speak truth to power, or songs of justice and freedom. “I’m talking about Adele singing, ‘Let the sky fall, when it crumbles, we will stand tall and face it all together.’ I’m talking about the Lord of the Rings and the Riders of Rohan screaming ‘Death!’ and just riding down into the deep of it, joyfully,” she said. “These [stories] speak about something that’s bigger than survival. It’s bigger than death and fear and suffering. Something that’s a bigger vision. Our cultures and our histories are full of beautiful, powerful poetry, and prayers and songs that all speak to this idea.”

However, as far as Grenfell-Lee can tell, even though we still tell these stories, they are no longer a part of our epistemological framework. Finding ways to re-incorporate narratives of fighting for what is right even though you are destined to lose is central to having successful climate communication. This isn’t to say that Grenfell-Lee thinks we are doomed, but given the uncertain nature of the future of humanity, having stories in our arsenal that remind us to keep fighting for what is right even when we know we will fail is essential.

One of the big things Grenfell-Lee hopes t0 help people in the climate space realize is that people don’t need more facts about climate change. “The more information we give people, the more frozen they get, the more scared they get, the more paralyzed they get,” she said. “People have just started realizing that the problem that we’re working on is not a science problem. It’s an ethics problem, and it’s a social issue and it’s a spiritual issue.”

For Grenfell-Lee it all comes back to the question: “What stories are we telling ourselves about what we’re observing and what we’re experiencing?”

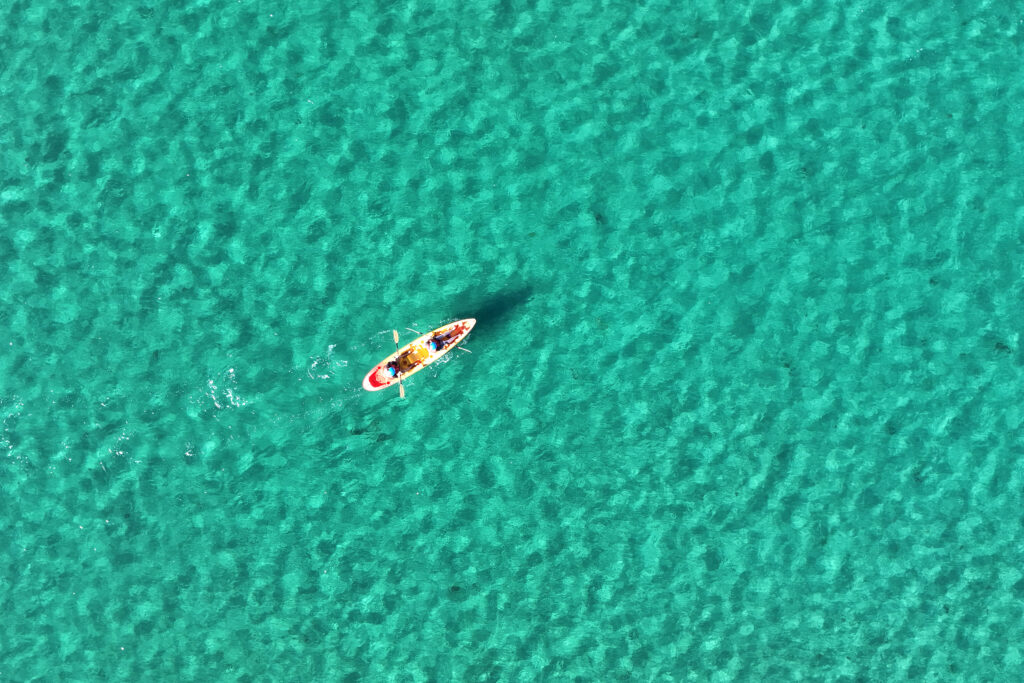

Indigenous Seascapes

Rosie Alegado is an ʻŌiwi (Native Hawaiian) scientist who studies Indigenous seascapes at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, where she directs the Microbial Ecology and Evolution in Hawai’i Lab (ME*E Lab). The ME*E Lab also collaborates with local coastal communities in Hawai’i on aquaculture and seascape health projects.

“When I talk about Indigenous seascapes, what I really mean is that these are coastal and marine spaces that have been occupied and managed by peoples for millenia,” said Alegado. “When I use the word Indigenous seascapes, I really mean a place that people think is wild and beautiful, but in actuality, it is intermittently tended to by Native communities. And it looks that way, because actually there’s a lot of stewardship happening. Like an aquatic forest garden.”

“We’re using Western scientific tools towards a purpose. They become just another lens to view the landscape from a different angle,” said Alegado. “It’s just another tool to increase the agency of our communities, so that our communities can co-manage their resources.”

“Many native cultures have experienced the apocalypse already. We were decimated, and we have come through, we survived and our cultures have evolved and adapted and we are resilient.”

— Rosie Alegado, an ʻŌiwi scientist

Her framework for understanding the climate crisis is based on both her community’s spiritual and cultural traditions, and also deeply informed by her perspective as a Kanaka ʻŌiwi.

Alegado recognizes why many people, particularly Westerners, seem to freeze when the topic of climate change comes up, she said. It’s hard to wrap your head around your way of life ceasing to exist, and even harder to see a potential future on the other side unless your culture and family have already survived the end of their world.

“Many native cultures have experienced the apocalypse already. We were decimated, and we have come through, we survived and our cultures have evolved and adapted and we are resilient,” said Alegado. “So, we’ve already worked through it… After something like that has already happened to you these kinds of existential threats just hit different.”

“I think for a lot of people who have never had something apocalyptic happen to them, they’re just losing their minds.” But, said Alegado, “change is a constant in a culture that is attuned to nature. I already know there are things in the environment that I will have to let go.”

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

Alegado points to her spiritual heritage as a native Hawaiian as one of the most influential pieces in her understanding of the relationship between humans and nature. “We don’t see humans as separate from nature. We are nestled systems within each other, not separate ecosystems,” she explained.

“Our belief systems teach us that humans impact nature, and nature impacts humans,” said Alegado “We have a reciprocal relationship with our gods. If we feed our gods carbon dioxide, of course what you can expect to get back is climate change!”

A Response to Dominionism

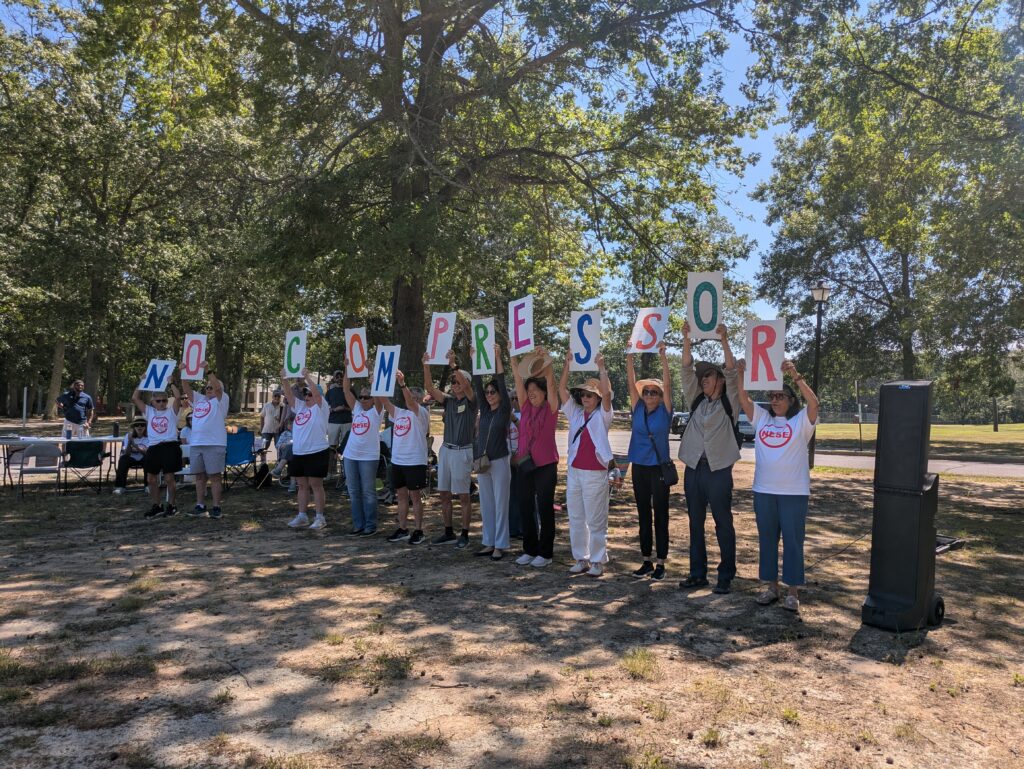

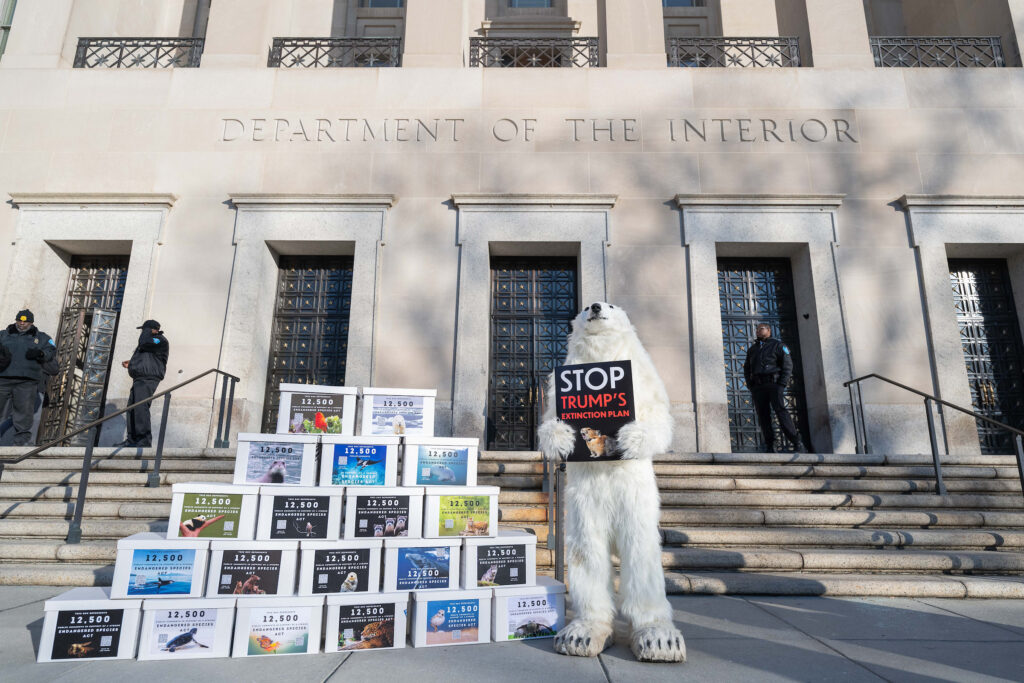

Heather McTeer Toney, a former congresswoman from Mississippi turned climate crusader, sees her own faith as a source of strength and knowledge in the face of the climate fight.

Raised in a community “steeped in faith,” she has always had a bedrock deep connection to her Pentecostal faith. Though she has always found guidance from the Bible’s teachings, the concept of dominionism never resonated with her.

Toney defines dominionism as the idea that God has given us this world and we are now here to rule over it and use it as we see fit. She is not alone in rejecting that philosophy; nearly all of the environmentally focused organizations rooted in the Christian faith have largely rejected that idea, said Toney.

We act from a place of understanding that God has given us the responsibility to care for creation, explained Toney. “That resonates back to the Black Christian responsibility, from a historical perspective of caring for one another, not wanting to repeat slavery and have dominion over others, but really respecting the space that God has given us to care for creation.”

Toney has also found a framework for her climate grief within her community’s interpretation of the Old Testament Book of Lamentations. Even in Lamentations, which is all about grief, sorrow and darkness, according to Toney, “there’s still these reminders throughout the lamentation that it’s not over and done. We are not cast aside… The Bible still reminds us throughout the book of sorrow that God has not forgotten us.”

Toney holds up her beliefs that we are not alone, and that there is hope, as pillars of strength when she is at her most drained. This heritage of hope and faith in God is something that, according to Toney, she has gained from a lifetime surrounded by people of faith.

The teachings, to rely on community care, have unwavering faith and hold onto hope even in the darkest times, echo through the generations in Black traditional churches, said Toney.

These traditions have kept us “through moments of reconstruction, moments of civil rights, and even this moment we’re in now, this is a moment we’ve lived before,” said Toney. “I fall back to that same tradition, to the feeling and the knowledge that I have ancestors who’ve been here before, they prayed their way through. I’m living in the blessings and prayers of ancestors who didn’t get to see this space. So I have absolutely no right whatsoever to fall down and wallow.”

Transcendent Compassion

To Grenfell-Lee, this ability to help people move from a place of sorrow to a place of hope and joy for the future they will not get to see—but are still able to revel in the possibility that someday, someone will—is what makes lament so powerful.

“Lament is a practice that places any kind of grief or rage or fear into a larger picture, where you then see, there is something bigger than my rage and my grief, there is something bigger and it’s big enough to hold it,” said Grenfell-Lee.

In her experience, lament requires taking a leap of faith and saying, “the Earth is big enough to hold my rage no matter how big my rage is. The universe is big enough to hold my grief no matter how big my grief is. Love is bigger, life is bigger. And that in and of itself is an act of radical trust.”

Through that trust, Grenfell-Lee believes space is created for peace, hope, gratitude, laughter and even joy. “It’s like a miracle. And that’s why the psalms of lament go through this place where they start with incomprehensible destruction and despair, and end with praise and thanksgiving.” It is like a template for finding our way through our most intense emotions, said Grenfell-Lee.

Some questions still keep Grenfell-Lee up at night. In the existential quiet of the night, she finds herself wondering whether as a species we have the capacity for magnanimity in the face of potential extinction.

“Can we do that, as humans? Can we offer that kind of faithfulness to the rest of the Earth, even if humanity doesn’t survive?” asked Grenfell-Lee. “Can we have a vision that’s bigger than survival, that’s about healing and wholeness and working together for the whole Earth and blessing them joyfully, blessing the rest of the creatures of this Earth with gratitude and joy and love, even if we know we won’t ever get to go home?”

Grenfell-Lee believes that to foster that sort of transcendent compassion, we need more stories where being the hero doesn’t come with a happily ever after. The stories we need right now are the ones where being the hero just means doing the right thing no matter what, even when it means you won’t ever get to go home, said Grenfell-Lee.

Only through finding cultural touchstones in narratives that celebrate unshakable hope, she said, can we build a foundation strong enough to stare down climate change—even when it means facing the apocalypse.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,