Gaslighting: Fourth in a series about opposition to a wave of new natural gas pipelines, power plants and storage facilities on the drawing board in North Carolina.

Listen to an audio version of this story below.

MOORESVILLE, N.C.—It’s a Tuesday night in mid-November, and the parking lot at Lake Norman High School is nearly full. I marvel at all the cars, and wedge my Prius into an empty space.

Police have stationed cars out front; security guards stand at the school’s entrance, not unheard of at a public hearing. Although the N.C. Division of Air Quality doesn’t usually draw large crowds for air permits, I think perhaps people are fired up about this one: Duke Energy plans to build new natural gas plants at the nearby Marshall Steam Station to replace two of the four coal-fired units.

For decades, neighbors of coal-fired plants in North Carolina have breathed polluted air belched by the smokestacks. Now they will have to contend with emissions from the new natural gas plants. A centerpiece of Duke’s controversial carbon plan, a target for environmental activists across the state, the plants will release millions of tons of greenhouse gases and other harmful compounds into the air.

Then I see the cheerleaders. The crowd had arrived for the Lake Norman High boys’ basketball team, which was hosting its season opener against North Lincoln.

Under bright lights, the packed gym reverberates. The bleachers are full. I hear the squeal of sneakers on hardwood, the occasional trill of the referee’s whistle, the thwack of a basketball. The hallway smells like popcorn.

A security guard waves me in, and I turn a corner and enter a dim, funereal auditorium, where two dozen or so people are dispersed among rows of empty seats.

Only four people had signed up to speak. Brittany Griffin, advocacy manager for CleanAIRE NC, a nonprofit group, was first on the agenda.

She is a Black woman in her 30s with black hair who had worked for AmeriCorps in New York City and learned how poor air quality harmed children in the South Bronx. She later earned a law degree and now lives in Charlotte.

Sitting toward the back of the auditorium, she reviewed her talking points, which she had written in a spiral notebook covered in a floral pattern: volatile organic compounds from the new natural gas plants would be even greater than those from the existing coal-fired units … chronic exposure can harm the heart, lungs, nervous system and reproductive organs, and cause cancer … children are especially vulnerable.

Wearing blue jeans and a crisp sweater with wide blue and white stripes, Griffin strode down the aisle to a microphone and faced the panel of three state officials, who were taking notes.

“I’m asking you to deny the permit or require substantial modifications,” Griffin said. “This permit fails to include adequate monitoring for dangerous pollutants.”

In swapping one polluting fossil fuel for another, state records show the new Marshall plants would emit less nitrogen oxide, fine particulate matter and sulfuric acid. However, state records show they would still release 316 tons of carbon monoxide, 63 tons of harmful volatile organic compounds, or VOCs, and 5.6 million tons of greenhouse gases, plus lead and other harmful pollutants, into the air each year.

The draft permit requires Duke to shutter two coal units after the natural gas plants begin generating energy, Griffin testified, but the utility could still simultaneously burn both types of fuel for years and spike pollutant levels.

Two of the Marshall coal units are scheduled to be retired in 2029 and the remaining two in 2032, according to the carbon plan.

“This permit needs an enforceable backstop so Duke can’t operate the coal plants longer than planned,” she said.

Speaker No. 3, Sheena Romasko, was collecting her thoughts when state officials called her name. She lives in NorthView Harbour, an upscale neighborhood of 350 homes next to Marshall Steam Station property and about a quarter mile from the boundary of the utility’s coal ash basin, which state records show holds about 12 million tons of the toxic waste material created by burning coal. Four million tons have already been excavated, according to Duke spokesman Bill Norton.

Romasko is in her late 30s, with long brown hair, and works for a solar installation company. She was miffed that Duke had failed to notify NorthView Harbour residents about the proposed natural gas plants.

“Duke said they forgot about us,” she testified. “They delivered notifications to everyone on the peninsula but our neighborhood.” When Duke did meet with neighbors, utility representatives couldn’t answer most of their questions, Romasko said, especially about air quality and surface water contamination. (Norton said Duke Energy had accidentally omitted NorthView Harbour from a notification for an open house held in February about the plants.)

Romasko’s house sits across the road from the site of the proposed plants. Like the other homeowners in the subdivision, she’s bound by a legal covenant with Crescent Resources prohibiting any activity that creates a nuisance or decreases property values.

To her, Duke should have to abide by the same rules. Nothing says nuisance, she thinks, like two gigantic natural gas plants at your doorstep.

Romasko sounded exasperated, her voice arch and tense. “I wonder why we’re still entertaining this,” she said, before returning to her seat.

The hearing ended within a half hour. The boys were still playing basketball. The next day I checked the box score: Lake Norman 69, North Lincoln 28.

Several days later, Griffin seemed disappointed. She had hoped more people would have attended, but also wished that state environmental regulators made information understandable to laypeople. That would go a long way in encouraging the public to participate.

“There’s the question of whether people were properly notified or not, and allowing folks to understand what is happening, what are the impacts, and having the time to organize the community, to show up and to really have their voice heard,” Griffin said. “I feel like they put the onus on the community to figure it out.”

It helps being a lawyer like Griffin when deciphering Duke’s carbon plan. The biennial roadmap that guides the utility in developing a “least-cost” energy mix of fossil fuels and renewables runs over 183 turgid pages. In early November the N.C. Utilities Commission approved it unanimously, over the objections of clean energy and environmental advocates.

Duke Energy argues that the state’s expansive economic growth, including the proliferation of data centers that consume enormous amounts of energy, means it must continue to burn fossil fuels, particularly natural gas, with more significant investments in solar, wind, battery storage and nuclear power to come later.

That reliance on natural gas comes at a price for the planet. In the carbon plan, the utility acknowledges it will blow past its 2030 deadline to reduce carbon emissions by 70 percent over 2005 levels.

Now, Duke says, it will shoot for 2035. Possibly 2036. Or even later.

By that time, the annual global average temperature, research shows, will regularly exceed 1.5 degrees Celsius above the 1850-1900 pre-industrial average. That’s the level set as the most ambitious target of the Paris Agreement, beyond which are even more dangerous climate tipping points.

Everyone alive today has experienced climate change. It started in the late 1800s, when coal began powering factories, steam engines and homes. Greenhouse gas emissions had yet to ramp up, and the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was 294 parts per million.

A century later, in 1988, levels had topped 350 ppm, which had been targeted as an aspirational “safe climate” level. Above that CO2 concentration, scientists say, the Earth’s climate can’t balance itself and the system can tip toward catastrophic changes. Today, average carbon dioxide levels have surpassed 420 ppm.

I remembered what Thomas Getz, speaker No. 4, had told state officials.

“Everything you’re experiencing was predicted 50 years ago,” Getz said. Scientists had foreseen a climate crisis, he told the officials, that would accelerate if people allowed more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. “In fact, it’s worse,” he said, “because it’s happening sooner. It’s an emergency.”

Tanya Hall, Born 1967, 332.3 Parts Per Million

Tanya Hall was speaker No. 2 at the air permit hearing. Originally from California, she is the chief operating officer of a solar company. She lives near her coworker Sheena Romasko in NorthView Harbour.

But Hall’s objections to the air permit go beyond her commitment to clean energy. She’s concerned about the risk of fires, explosions, noise pollution and toxic chemicals entering the air from the new natural gas units. She’s concerned about how schools, day care centers and homes would be evacuated on streets that are narrow and circuitous. Many dead-end at the lake.

In her 17 years of owning a home in NorthView Harbour, Hall has seen enough to erode any faith that the state Department of Environmental Quality will ensure the utility complies with environmental laws in building and operating the new natural gas plants.

“We have been subjected long enough to the lack of oversight by DEQ,” Hall said.

Since moving to the community in 2007, Hall has witnessed how pollution from the Marshall plant has harmed her neighborhood—and, she believes, her own health. If Duke can’t manage its coal ash in the air and groundwater, Hall wondered, how could anyone expect the utility to responsibly build and maintain two natural gas plants?

“I have no faith in their ability to control any contamination within the air or water that comes from their plants,” Hall said after the meeting. “They have 30-plus years of non-compliance. The health risks are too great around this.”

Hall is thin, blonde, with high cheekbones and blue eyes. When she arrived at NorthView Harbour, she was unaware of contamination emanating from the Marshall plant. But immediately she began noticing the fine dust accumulating on her car in the mornings. “It looked like ashtrays were dumped on my car,” she said. “I actually asked some neighbors, who told me that it was from the steam station less than a half mile away blowing fly ash on my car.”

Her daughter, then 3, at times had to use a nebulizer to help her breathe.

Hall said she called Duke and spoke with a manager, who told her the ash coming from Marshall was “safe and nonhazardous.”

The manager no longer works for Duke Energy; Norton, the spokesman, said the utility has no record of the conversation.

Then in 2017, Hall’s back began to ache, an unremarkable complaint for someone who’s 50.

Doctors took a CT scan. They detected a tumor on her kidney. Hall called her husband and immediately thought of her daughter, then a teenager, who would grow up, get married and live a full life without her.

Hall didn’t smoke or have high blood pressure and wasn’t overweight, elderly or male, all risk factors for this type of cancer. But during the previous decade, she had lived in NorthView Harbour, next to Duke Energy’s Marshall Steam Station. Among the many cancer-causing chemicals, coal ash contains cadmium, exposure to which is a risk factor for kidney cancer, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

NorthView Harbour lies just across the peninsula from ZIP code 28117, where state epidemiologists found that from 2012 to 2016, incidences of thyroid cancer were triple what would be expected. In the adjacent 28115, the number was double what would be expected, especially in young women, at an age when it’s rare.

Investigators haven’t pinpointed a cause for the cancers. Norton, the Duke Energy spokesman, said the utility “is unaware of any scientific evidence to support a link between health effects and coal ash, and there is a considerable body of scientific research that runs counter to such speculation.”

But last year the EPA determined that coal ash is more toxic than previously known. Low levels of arsenic and gamma radiation, present in coal ash, drive an increased cancer risk, the EPA found, even when the ash composes just 2 percent of the soil mixture. At 8 percent, the risk levels are high enough to trigger EPA regulation.

Hall thought she would retire at NorthView Harbour, but not any more. The natural gas plants and the menace of coal ash could drive her out. Now 57 and missing part of a kidney, Hall recently sued Duke Energy, alleging her cancer was linked to exposure to coal ash.

For years she has undergone additional screenings to ensure her scans are clean. She recently had an MRI, which spotted a nodule on her thyroid gland. It could be nothing. Yet she’s worried because of the prevalence of thyroid cancer around her neighborhood. The stress of the cancer returning—or showing up elsewhere—never goes away.

Hope Taylor, Born 1952, 312.2 Parts Per Million

Another Tuesday in mid-November and another air permit hearing, this time about the proposed two new natural gas plants at Hyco Lake, north of Roxboro. Like their counterparts, the Marshall plants, the units would replace those that currently burn coal.

The auditorium at Piedmont Community College was brightly lit. Thirty-six people showed up and 20 of them spoke. The vibe was like a family reunion among environmentalists.

In the fourth row, Hope Taylor, executive director of the nonprofit Clean Water for North Carolina, reviewed her notes and waited her turn. She’s fastidious about her comments. She spends hours writing them and tries to channel a controlled outrage, grounded in facts but with just enough emotion to make it clear how unacceptable the conditions are.

“I have grave concerns about this permit,” she told the panel of six state officials, who were taking notes.

She went down a list. Air pollution. Public health. Delays in complying with greenhouse gas emission reductions, as required by state law. No enforceable date for the existing power plants to stop burning coal.

If Duke can’t find a way to reduce or capture the carbon emissions by 90 percent, then according to new EPA rules, Hyco Lake can generate power only 40 percent of the time. When Duke shuts down and restarts the plants to remain under that threshold, it releases more pollution than if the plant operated around the clock. Worse yet, Taylor said, air permits usually exempt utilities from emissions rules during shutdown and start up.

Despite the pollution issues, county officials support the plants. Duke Energy is key to sustaining the local economy, responsible for about 20 percent of the county’s property tax base. Duke, whose annual gross revenue last year was $29 billion, also donates hundreds of thousands of dollars to local charities through its foundation.

For Taylor, these figures only reinforced how dependent the county’s economy has become on Duke Energy.

“You must deny this permit to prevent the further energy colonization of Person County,” Taylor said.

Energy colonization. She was glad she finally got to use that term.

Taylor lives eight miles from the Person County line down a long driveway, where she raises dairy goats near the small town of Stem. Gourds decorate the wooden front steps to her yellow, 780-square-foot house that she shares with two cats, Vesper and Ducky, and a black lab, Midnight.

A sunroom, about the size of a service elevator, faces south toward a meadow and warms the kitchen. At night Taylor likes to sit there and peer through a telescope to gaze at the stars or watch the Perseid meteor showers.

From a small table that straddles the kitchen and the sunroom, she has used her position at Clean Water for North Carolina to fight Duke Energy and the fossil fuel industry on numerous fronts: the now-defunct Atlantic Coast Pipeline, fracking and coal ash contamination in drinking water wells.

Now she’s battling the enormous natural gas buildout and the document that’s supporting it: Duke Energy’s carbon plan.

“You must deny this permit to prevent the further energy colonization of Person County.”

Taylor is 72, with brown eyes and short, silver hair swept over her eyebrows. Originally from the West Coast, Taylor graduated from the University of Maryland with a biochemistry degree when few women were in the field. After graduating, she took a job at the National Institutes of Health. For a young biochemist, the position offered stimulating intellectual and scientific challenges; it also helped that the interviewer didn’t ask her when she expected to have children.

Taylor, though, wanted to work close to the land and later moved to a farm in West Virginia, where she lived off the grid in a yurt. In 1985, she moved to North Carolina to work at the Duke University Medical Center, studying protein structures. She then parlayed her scientific expertise into environmental advocacy.

The late afternoon sun poured into her house and filtered through a fig tree outside a window. Unripe fruit still hung from the bare branches. It was unusual, having green figs this time of year. Taylor blamed June, a dastardly hot and dry month when the trees were using their energy trying to survive. Climate change ruined the figs.

Taylor’s kitchen table is a snowdrift of environmental documents. Here she has spent hours dissecting Duke Energy’s carbon plan. As she read it, she was dismayed at the Utilities Commission’s almost naive trust in Duke’s energy demand modeling and the agency’s disregard for opponents who couldn’t afford thousands of dollars on their own modeling software.

Of the seven utilities commissioners, only one, Jeff Hughes, mentioned climate change in the ruling. No commissioner addressed the public health risks from air pollution.

The carbon plan is a centerpiece of House Bill 951, legislation that passed with bipartisan, albeit not unanimous, support in 2021 and was signed into law by Gov. Roy Cooper, a Democrat. At the time, state lawmakers, Cooper and many environmental advocates heralded the legislation as a game-changer in decarbonizing North Carolina.

There was a glaring omission. While the bill requires Duke to sharply reduce its carbon emissions, the word “methane” appears nowhere in it. Methane, the primary component of natural gas, is a climate super-pollutant, 80 times more warming than carbon dioxide over a 20-year period. It leaks from fracking wells, pipelines, compressor stations and power plants.

That omission gave Duke and state lawmakers cover for the natural gas buildout. Now it’s nearly impossible to strengthen energy legislation. The Republicans have held a majority or supermajority in the legislature ever since.

“We should have asked for amendments,” Taylor said. There was a tinge of regret in her voice. “We’re really paying for it now, with the carbon plan.”

Duke Energy says “new natural gas generation and its accompanying infrastructure is an essential part of meeting the state’s carbon reduction goals by enabling coal retirements and providing critical support for weather-dependent renewables. … A diverse resource mix is absolutely critical to maintaining the Carolinas’ competitive advantage.”

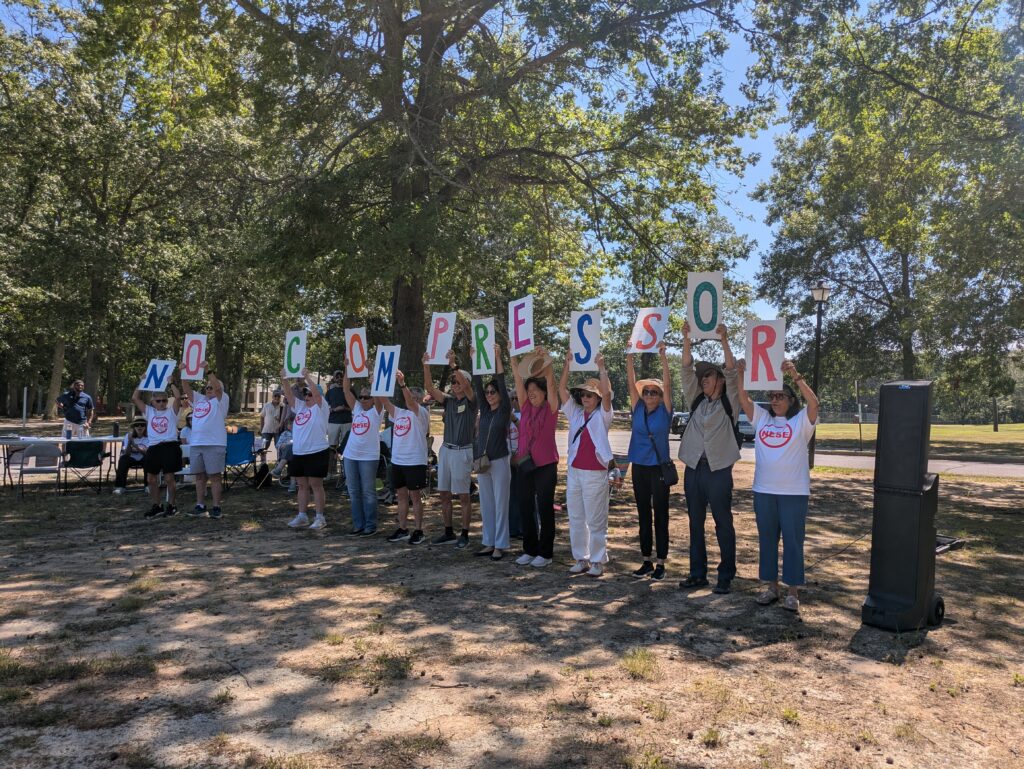

Taylor sees the fight against the natural gas buildout as a much different one than that of eight years ago. That’s when grassroots advocacy groups, led by activists from communities of color, battled the Atlantic Coast Pipeline—and eventually won.

Since then, Taylor has noticed energy companies have changed tactics. They got better at their own game.

Instead of one large project, the new buildout is fragmented, with pipelines, compressor stations and a liquified natural gas plant spread all over central and southern North Carolina. Each project has its own state or federal regulations, ownership, permits, timelines and documents. Affected communities are strung over hundreds of miles in a half-dozen counties.

“There is an advantage in having one long pipeline for organizing purposes,” Taylor said. “Instead of a continuous, 600-mile collaboration, we have apparently disconnected fights.”

Even in neighborhoods around the Hyco Lake plant, there is not a consensus about how to transition to clean energy. Residents have told Taylor that the coal-fired plants are cleaner than they used to be.

So why not keep burning coal? several residents told her.

Taylor felt a little shocked but came to understand their viewpoint. Spend the money that would go toward building the natural gas plants and pipelines on a permanent, more cost-effective solution—wind and solar. Duke is framing natural gas as the bridge fuel to renewables. Some residents are saying, don’t use the bridge.

In early December, the N.C. Utilities Commission approved that bridge, issuing certificates of necessity for the Hyco Lake and Marshall Steam Station natural gas plants. The Department of Environmental Quality has yet to approve the air permits, but it’s expected to do so.

Taylor was prepared for the setback. Her previous fights have shown that environmental progress is incremental. She’s aware that part of her responsibility is to keep a community’s hope alive, to reassure people that if their argument doesn’t work this time, it still might later.

Bobby Jones, Born 1950, 311.2 Parts Per Million

About 100 miles southeast of Taylor’s home in Stem, on a sunny day in early December, fellow activist Bobby Jones cruised in his car through the rural outskirts of Goldsboro, the radio tuned to smooth jazz. He is a tall, bald, Black man with deep brown, hooded eyes, a wide grin and a wiry, gray soul patch that extends from his chin.

Jones passed the Neuse River, which flooded in Hurricane Matthew eight years ago. He passed enormous hog farms whose waste seeps into the groundwater. He drove by small and tidy houses, whose wells had become contaminated by leaking ponds of coal ash at Duke Energy’s nearby H.F. Lee plant.

Jones slowed down at the former home of his best friend, John Gurley, an environmental justice advocate, who died of cancer last year. Gurley was white and helped Jones get a foothold in neighborhoods that otherwise would not welcome him.

“He was the most courageous man I’ve ever known,” Jones said.

Jones stopped in front of an old mobile home, where Jennifer Worrell, another environmental activist, lived.

“She was tough,” Jones said. “I saw her walk out in front of one of these trucks whose driver told her he was hauling coal ash.”

She died of cancer, too.

“We know what Duke Energy is all about, and we have the scars to prove it.”

Outside the driver’s side window, the occasional Confederate flag blew stiff in the breeze. Before the election, Jones could ignore the flags as just part of the scenery. But with President-elect Donald Trump’s new administration looming six weeks away, Jones noticed them more. Now those symbols of hate had a bite.

A week earlier, Jones had attended a public meeting held by the NC Clean Energy Technology Center, housed at NC State University. The center had sent a team to Goldsboro to receive feedback about Duke Energy’s proposal for the “red zone.” These are areas with great potential for large solar farms, but need high-voltage lines and towers to transmit the power. They are also a key clean energy component in Duke’s carbon plan.

Goldsboro is in the middle of the red zone. Some residents, including Jones, feel wary of the utility’s proposal, not because they oppose solar energy—very much the opposite—but because Duke is in charge of the projects. Residents are concerned that disenfranchised areas, often communities of color, would lose land to eminent domain, yet reap little of solar energy’s benefits. They would prefer widespread rooftop solar installation to utility-scale projects, although there are technical challenges to the former.

“We are very pro-clean energy,” Jones said at the meeting. “But we know what Duke Energy is all about, and we have the scars to prove it.”

Jones is almost 74 years old. As a child, he helped his family pick cotton and tobacco throughout eastern North Carolina and remembers being doused with DDT while working in the fields. They didn’t know how to protect themselves, so some people got sick, and others died.

Jones graduated from a segregated high school. As a young man, he attended N.C. A&T, then transferred to a college in Colorado, where he took up backpacking as a hobby and felt a deep connection with the environment that would continue all his life.

With a degree in clinical psychology, Jones worked for 30 years for the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, helping people with mental illness and intellectual disabilities; he developed, implemented and directed various programs across the state. After he retired, he founded the Down East Coal Ash Environmental and Social Justice Coalition, which advocates for people in eastern North Carolina burdened by pollution.

Jones stopped at an RV park near the Neuse River, where people live year-round. His family couldn’t afford to go to the beach when he was a boy, so they headed to the river, where they caught catfish and swam. Even now, he still feels deeply protective of the Neuse. “For my culture and like Indigenous cultures,” Jones said, “it’s pretty commonplace for a river or tree or valley to take on human attributes.”

He headed down a dead-end road to the primary reason he mistrusts Duke. “I know Duke Energy, and I know what they want”—profit, Jones said. “They don’t give a damn about my community or any other community.”

He arrived in front of Duke Energy’s STAR facility, an enormous white dome that looks like a space observatory, flanked by a smokestack exhaling clouds of emissions.

Jones parked his car facing out, toward the exit.

In 2016, the state legislature required Duke to identify places in North Carolina to burn ash for “beneficial reuse.” The utility chose three, including Goldsboro.

The ash comes from the old unlined ponds next door at the H.F. Lee Plant, which burned coal until 2012, when Duke replaced it with a natural gas unit.

But the contamination from H.F. Lee has not always been contained.

In 2014, after the disastrous Dan River coal ash spill in Rockingham County, Jones wondered if the H.F. Lee plant was releasing contamination into the Neuse.

Then one day Jones said he got a phone call from a stranger, a man.

“‘Meet me tonight at 11 o’clock and I’m gonna take you on a boat. I’ll show you,’” he remembered the man telling him.

Jones felt nervous but also intrigued and wanted to get the proof. He asked if he could bring someone. The man agreed.

At 11 o’clock on a dark, chilly night, Jones said, he and John Gurley showed up at the Neuse River meeting place. Two white men were there, both carrying guns, Jones remembered.

“Me and John, we got on their boat and they took us on the Neuse to Duke property,” Jones said. The men stood guard as Jones and Gurley walked as far as they could go without being caught.

They took pictures and video of what they said was discharge from the plant entering the river. Without testing, it’s impossible to know what chemicals the discharge contained—Duke’s Norton said it was likely stormwater—but Jones believes it was contaminated with ash.

Jones never learned the men’s names or where they were from. “I really don’t want to say that I’m fearless, but in a situation like this, they had the same love for the Neuse and for the community as I did,” he said. “We connected on those grounds.”

Another release occurred in 2016, when floodwaters from Hurricane Matthew overtopped several inactive coal ash basins and released fly ash and related particles known as cenospheres into the Neuse River, the drinking water supply for the city of Goldsboro and other communities downstream.

Waterkeepers found high levels of arsenic in the Neuse nearest to the old ash basins after Matthew; Duke and the state sampled in different locations and found much lower concentrations.

In 2018, after Hurricane Florence, releases happened again.

More recently, in 2021, roughly 150 tons of the ash escaped through a door at the STAR facility, but stayed on the property.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

In his car, Jones passed an old state prison. It’s now closed, but razor wire that remains around the perimeter fence glitters in the sun like tinsel on a Christmas tree. He thought about his four children, his grandchildren, his community, all those lives being altered by climate change even as Duke’s carbon plan still relies on burning—coal, gas, diesel oil, even poultry and hog waste—to generate electricity.

“I know my children and grandchildren will not be the ones who can afford clean water and clean air,” Jones said. “They will be the ones relegated to cancer alleys. So I’ve got to fight. And I’ve got to encourage others to fight. Because we already see climate change. We don’t have to wait for it to happen.”

Jones often thinks of the final words of John Gurley, as cancer had hollowed out his body. “The last conversation we had, we were talking about Duke Energy. And he said, ‘Bobby, hold them accountable.’”

Carrboro, N.C., Incorporated 1911, 300.6 Parts Per Million

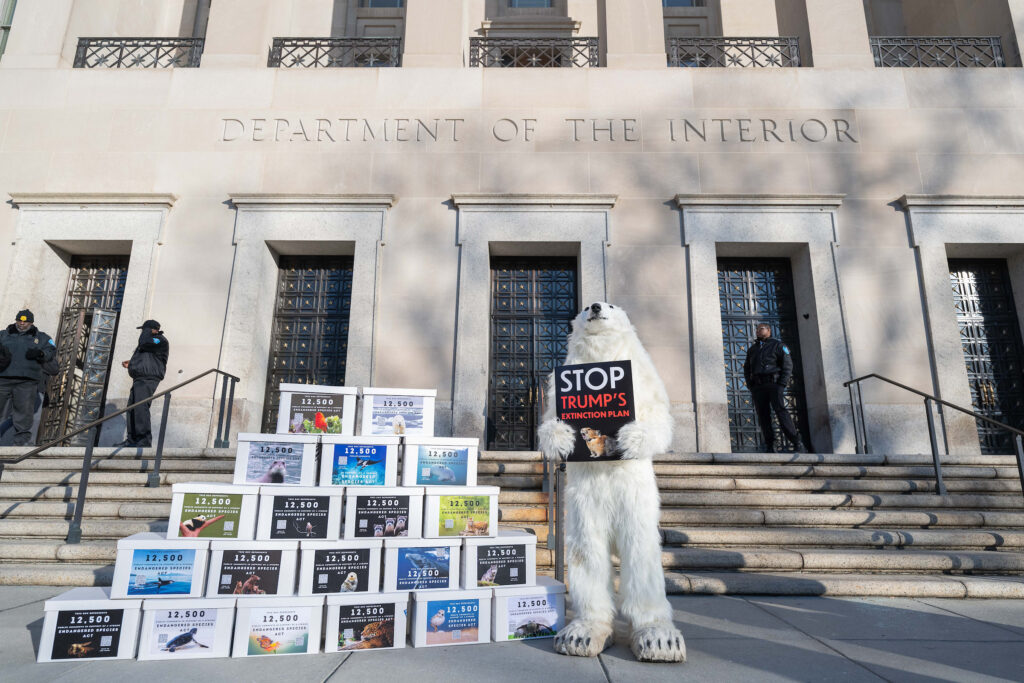

Later that same day in early December, the North Carolina town of Carrboro sued Duke Energy for its contribution to climate change.

Carrboro, population 21,000, is one of the few small towns in North Carolina where a car isn’t necessary to live. It lies just west of Chapel Hill, six-and-a-half square miles of historic neighborhoods and old mill houses, arts centers and communal spaces, bisected by a railroad and bordered by the countryside.

The town’s lawsuit cites a recent report by the Energy and Policy Institute, a watchdog group, alleging that Duke had misled the public about the dangers fossil fuels posed to the global climate.

“The nationwide climate deception scheme has worsened the climate crisis, harmed the community and cost the town millions of dollars” by delaying the transition from planet-heating fossil fuels to renewable energy, the lawsuit reads.

“Our job is to speak truth to power, and that means holding Duke Energy Corp., the third- largest climate polluting corporation in the United States and one of the largest corporate polluters in the world, accountable for its actions,” said Mayor Barbara Foushee at a press conference at Town Hall.

Since 2012, Carrboro has experienced more than 100 flooding events, according to a town map, the frequency and intensity of which have been at least partially revved up by climate change.

Jean Su (left), senior attorney and energy justice program director at the Center for Biological Diversity, and NC WARN Executive Director Jim Warren speak during the Town Hall press conference. “They’re making the global climate crisis worse despite widespread and accelerating misery,” Warren said of Duke Energy. Credit: Town of Carrboro

As a result, Carrboro has incurred tens of millions of dollars in costs to improve drainage, repair roads and weatherize homes of low-income residents. Now, Carrboro officials want Duke to pay not just for the past harms, but future ones induced by climate change.

Duke issued a statement saying it is reviewing the complaint and “will continue working with policymakers and regulators to deliver reliable and increasingly clean energy while keeping rates as low as possible.”

Beside Foushee stood a phalanx of town officials, lawyers and Jim Warren, executive director of NC WARN, a friend of Bobby Jones and a longtime critic of Duke Energy. The nonprofit, which has sued Duke several times over renewable energy policies—unsuccessfully—is paying for the lawsuit.

“Duke’s bosses keep expanding the use of fossil fuels, expanding methane—a disastrous move, according to climate scientists,” Warren said.

I had just spent the afternoon with Bobby Jones and watched the press conference online from a Sheetz parking lot. It occurred to me that at its heart, Carrboro’s lawsuit could be read as a condemnation of the Duke Energy carbon plan: a mammoth ramp up of natural gas, with the largest investments in renewables coming when it might be too late.

I reflected on my own naivete upon pulling into the parking lot at Lake Norman High School, thinking for a moment that all those people had turned out for an air permit hearing. But as I find myself obsessing about the fate of the planet, I understand the activists’ focus on the carbon plan, now that the state has blessed extending Duke’s deadline for emissions reductions by five or six years.

When I was in college, we’d already reached the upper-limit “safe” level for carbon dioxide in the atmosphere of 350 ppm. Now, we’re at 420 ppm.

As Thomas Getz, speaker No. 4 back at Lake Norman High School, said, “It’s an emergency.” And the most frightening question that raises for me is this: How much time do we have?

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,