Scott Kane, co-founder and co-owner of a solar company operating in Utah and Wyoming, does not work on the utility side of the industry, but when the United States Geological Survey released its map of utility-scale solar projects across the country late last year, he took an immediate interest. Kane is deeply invested in the country’s clean energy transition, and was curious to see how large-scale solar was growing across the country.

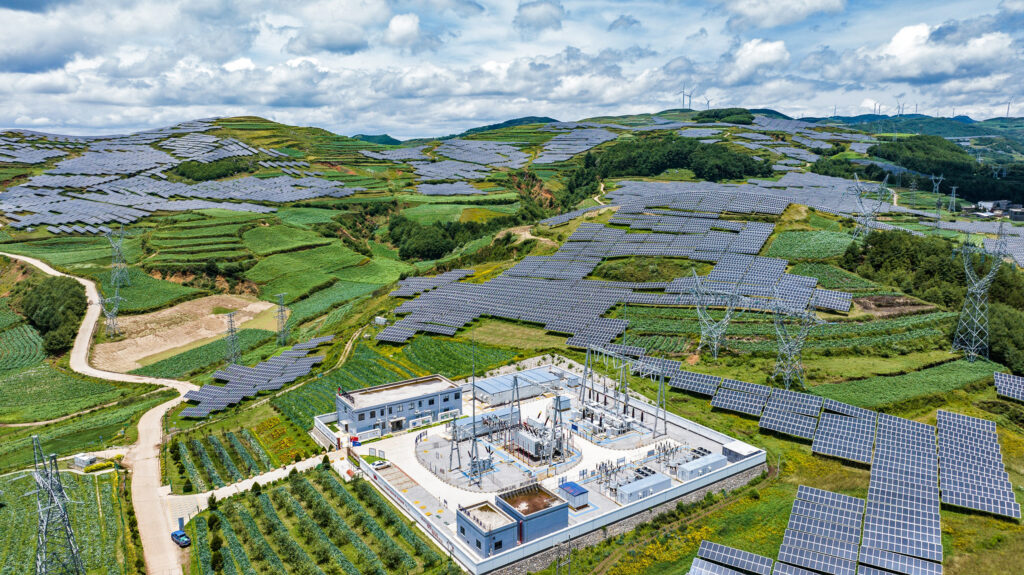

The map showed the location and capacity of ground mounted solar arrays connected directly to a utility’s portion of the grid capable of producing at least one megawatt of power, the industry’s definition of “utility-scale.” Initially, the map held few surprises. States like California, Colorado and Florida, all famous for their sunshine, showed dense clusters of projects. The midwest and northeast were less ambitious in their solar power generation, but had their fair share of facilities, too.

Kane began tinkering with some of the sliders on the map. He moved the “capacity” slider up to 10 megawatts, enough energy to represent a meaningful investment in solar but not so much that most of the dots on the map would disappear. When the map rerendered half a second later, Kane was shocked.

The sun belt, southeast and northeast still showed a large number of clusters; the midwest and northwest, which see less sunshine, had diminished to only a smattering of dots. But two huge swaths of the country containing solid solar resources were almost completely unoccupied by solar projects over 10 megawatts: Appalachia, and the Eastern Rockies.

Explore the latest news about what’s at stake for the climate during this election season.

To illustrate the point, Kane took a screenshot of the map, drew two large red shapes around each of those regions, and emailed it to a colleague interested in Wyoming’s clean energy sector. There appears to be “some invisible force field” that is “preventing large-scale solar from entering our region of the country,” he wrote.

Retracing Kane’s steps on the map shows an almost identical situation today, although four new utility-scale projects are under development in Wyoming.

Wyoming, like many of the neighboring states without larger solar development on the map—Idaho, Montana, the Dakotas, Nebraska and Kansas—has a perfectly suitable solar resource. Much of the state sits 6,000 feet or higher from sea level, making it windier and colder, and daily summer highs are not too punishing—usually in the mid 70s, according to National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration weather data. These conditions, bright with a crisp air, are ideal for solar energy development as panels become inefficient if they overheat.

And yet, Wyoming is home to only two utility-scale solar farms. Solar energy is soaring in other Western states, and prices for the equipment continue to fall, but utility-scale solar projects have not yet caught on in Wyoming.

The state’s famously small population—the country’s lowest—subsists on an economy deeply intertwined with fossil fuels; residents pay no income tax, and the state makes a large portion of its tax revenue from extractive industries. It is also deeply conservative—the very fact of climate change is contested by some state politicians. Gov. Mark Gordon, who is not among Wyoming’s climate deniers, has touted an “all of the above” energy policy that has, so far, poured state-taxpayer money into fledgling technologies like carbon capture and sequestration lawmakers unabashedly hope can extend the life of coal and other fossil fuel industries and infrastructure.

Despite these headwinds, other forms of emissions-free energy have gained a foothold in the state: southern Wyoming is home to some of the nation’s best inland wind resources, and, accordingly, there are some 1,500 wind turbines there. Last month, Bill Gates visited a site near Kemmerer, Wyoming, to break ground on a novel nuclear reactor his company, TerraPower, is building in the struggling coal town.

“We have such an opportunity for developing utility-scale solar,” Kane said. But something is holding it back. “I can’t help but think that it is related to the incumbent industry in this part of the country.”

Coal Over Solar

Appalachia and the eastern Rockies have, historically, been the bedrock of the U.S. coal industry. Mining companies and utilities in both regions have honed the process of mining and burning coal for energy over decades, building a mature industry boosted by federal subsidies. As a result, despite the clean energy transition, coal remains the number one source of energy generation in the several Western states today, according to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

“Coal’s dominance in the region makes it harder to bring solar online just because there’s a lot of political, economic and cultural barriers that are keeping developers from being able to build in these areas,” said Vivian Yang, an energy analyst at the Union of Concerned Scientists, a clean energy advocacy nonprofit that monitors the country’s energy transition. Unlike some of its neighbors in the West, Wyoming has no state laws requiring utilities operating there to generate a certain amount of electricity from renewable sources in the coming decades. Without such policies there’s “a lot of uncertainty and risk for the development of renewables in the market,” Yang said. She added that disparaging comments from state leaders about renewable energy may make developers skittish to bring new solar farms to Wyoming.

But the presence of coal may not totally account for a stunted solar industry in the West, said Dave Eskelsen, a spokesperson for Rocky Mountain Power, which provides electricity to customers in Idaho, Utah and Wyoming. The company is a division of PacifiCorp, a large utility that also serves California, Oregon and Washington.

Eskelsen acknowledged that, in Wyoming, there have been fewer solar resources “coming into” the utility’s integrated resource plans, a document that estimates, among other things, the company’s future energy needs and how it plans to meet them. He couldn’t say for sure why that might be, but noted that the most important factors facing any new energy project—regardless of how the energy is generated—are “availability of resources, and proximity to a transmission interconnection.”

Yang saw this as a limiting factor, too. “There just isn’t enough transmission” for new solar projects in many places, she said. “Throughout the country we’re just struggling with insufficient transmission to get more clean energy online.”

A new power plant located near existing grid infrastructure will have lower costs associated with its interconnection, savings that can sometimes make a difference to developers and a utility regardless of how the electricity is generated. For that reason, Eskelsen was wary of singling out coal as the main reason solar is lagging in Wyoming. “That’s too simple an argument,” he said.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

Wyoming’s wind industry represents a renewable energy source that was proliferating at the utility scale in Wyoming because it has, in many cases, a smooth runway to the grid and an excellent resource, he said. “One of the reasons we have most of our wind resources located in Wyoming is because the wind density in certain places in Wyoming is very favorable, and it produces a very high capacity wind resource. Renewables, he added, have “been very, very beneficial to our customers” because they do not carry a fuel cost, which can help keep electricity bills lower.

But for solar development, the company has had success at lower latitudes farther south, particularly in Utah. The Beehive State and other parts of the Sun Belt, “tend to produce better [solar] sites,” he said.

Change on the Horizon?

But the slow development of utility-scale solar projects in many coal states may be changing, at least in Wyoming. The state’s Industrial Siting Council, one of the principal bodies that issues development permits, lists four utility-scale solar projects under development. The average energy value for those projects is 320 megawatts, more than double the size of either of Wyoming’s existing solar facilities.

This is important progress for the state, said Kane. “There is economic development happening at a really large scale in surrounding states that is much reduced here.” Wyoming has missed out on hundreds of millions of dollars in sales and property tax revenue, he continued.

Utility-scale solar farms could be located in almost every Wyoming county, he said, except Park and Teton counties, which are home to large national parks and national forests that are likely more valuable to locals as in-tact recreation and conservation ecosystems. As a result, solar energy could be a “much more evenly distributed tax generator” compared with the fossil fuel industry, which generates local tax revenue in communities where coal, oil and gas are extracted that is then, by law, redistributed to other communities, Kane said. In addition to sales and property taxes, fossil fuel companies are also taxed for extracting minerals from the ground in Wyoming; there is no comparable tax the state could levy on the renewable energy industry, and as a result, the tax revenue from the solar industry would not completely replace the dollars generated by fossil fuel taxes.

“There is economic development happening at a really large scale in surrounding states that is much reduced here.”

There’s a jobs factor, too. According to data and research by the Interstate Renewable Energy Council, Wyoming had 165 jobs in the solar industry in 2022. That figure paled in comparison to neighboring states like Colorado and Utah, each home to more than 7,000 such jobs. Even Montana and Idaho, states that lack robust utility-scale solar, had more than double the Cowboy state’s figure. Like taxes, jobs associated with large-scale solar development could also be more democratically spread out across Wyoming, Kane said.

Waiting too long to take advantage of this new industry could carry more than just economic consequences for Wyoming. The emissions from burning coal are bringing climate and health consequences that can be “really devastating” for local communities, Yang said. And the continued reliance on coal for electricity generation will also hit utility customers’ pocketbooks, she added. Since operating a solar power plant is cheaper than running virtually any coal power plant in the country (the lone exception being Dry Fork in Campbell County, Wyoming), state ratepayers will continue to fork over more money to utilities if coal is kept online and solar is kept off the grid, she said.

But with at least four more projects in the pipeline, Wyoming’s grid could soon experience a seven-fold increase in the amount of solar electricity it carries. If every project in the state’s permit pipeline were approved and built, Wyoming would have more solar farms rated over 80 megawatts than every other Rocky Mountain state except Utah.

Kane was pleased to hear those numbers, but, after years of hearing about similar projects and rarely seeing them constructed, he doesn’t put much stock into plans.

“I feel like there have been headlines for the last five years of utility-scale solar projects coming to Wyoming,” he said. “But few of them have seen the light of day.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,