This year’s annual United Nations climate talks in Bonn started the way COP28 in Dubai ended last December, with some representatives from developing countries in the Global South feeling excluded from the process and even unwanted.

“Do we really need to stay in Bonn for such conferences,” said Proscovier Nnanyonjo Vikman, co-director of Climate Change Action East Africa, which is part of the global Climate Action Network spanning civil society groups in 130 countries.

”Can we go to another country that is accommodating and would see where we are coming from?” she asked at a June 8 press conference after describing how visa problems prevented her from arriving in Bonn on time.

We’re hiring!

Please take a look at the new openings in our newsroom.

See jobs

The Bonn talks are held each year in June to prepare the ground for the full-blown COP climate summits hosted by a different country each year in November or December. The Bonn meetings are smaller and more technical, which can give developing countries a chance to have more influence, she said.

“By the time COP happens, most decisions have already been made in Bonn. If you can’t access that, that is a violation of your rights,” she said, adding that it wasn’t just civil society groups that had problems getting into Germany, but even government officials from the African region who reported visa challenges.

“I’m raising this because every time we have a Bonn conference, these hurdles come up,” she said. “We cannot just be begging to be in the space, and yet at the same time, we’re the ones having to bear the brunt of the climate crisis.”

Her words echoed the end of COP28, when John Silk, head of the Marshall Islands delegation, said that the outcome of the Dubai meeting was not inclusive because it was approved “without a major group in the room.”

Several representatives of the 39-member Association of Small Island States were still outside the closing plenary finalizing their position when COP28 president Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber gavelled the final approval of the outcome, the UAE Consensus. That agreement, which culminated last December’s climate summit, actually marked “a step backward,” said an AOSIS statement after the summit, decrying the absence of any enforceable measures to cut greenhouse gas pollution enough to slow sea level rise.

It’s not a new issue. At COP26 in Glasgow, some developing countries were kept out of key meetings on climate finance, prompting a sharp letter from United Nations Special Rapporteur David Boyd, who wrote that many people from climate vulnerable regions would not be heard because of “multiple barriers to meaningful participation.”

Recurrent access issues for developing countries in the climate negotiations indicate a systemic problem, said Vikman.

“The voices that should be at the table are pushed out,” she said. “There is an injustice happening and we need to address it. I think we need to decolonize the system.”

Shrinking Civic Spaces

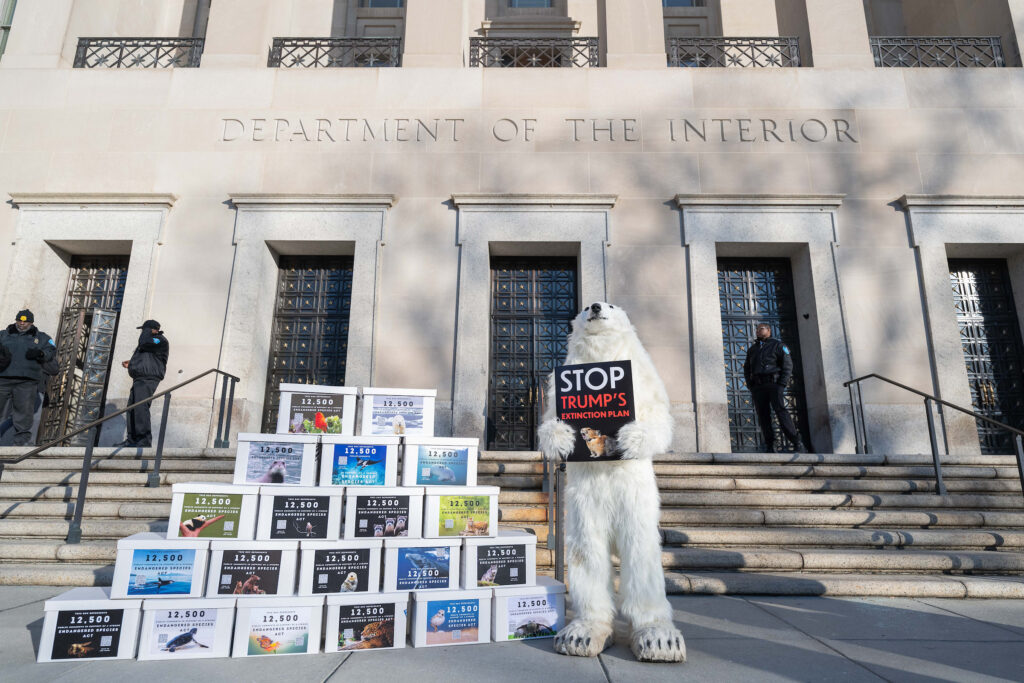

Representatives of developing nations and social scientists note that robust civil society voices enrich global climate negotiations and contribute to better outcomes, but societal trends appear to be moving away from including them, with repression of climate activists and other environmental advocates and defenders on the rise around the world, according to a recent United Nations position paper.

“What we’re facing is civic space shrinking around the whole world,” said Ann Harrison, a senior advocate with Amnesty International. Environmental and human rights advocates are facing an “array of intimidatory tactics and sometimes violence and all too often, murder.”

In some cases, she continued, governments are directly responsible, at other times they stand by while private security forces stifle dissent on behalf of corporate interests, she said, adding that such repression was noticeable at all recent climate summits, including COP26 in the United Kingdom, a country with an “increasing official intolerance to peaceful environmental protest and climate protest,” she said.

“We all need these rights to be in place so we can all hold our governments to account for the actions they take, or indeed, actually fail to take.”

Ahead of 2022’s COP27 in Egypt, the government rounded up at least 1,500 people supposedly in connection with what was being called a climate revolt, and about 1,100 of them are still imprisoned, she said. In the United Arab Emirates, which hosted last year’s COP28, the activities of civil society groups are not tolerated at all, she said.

“It’s impossible to protest safely in the streets, and there are many human rights defenders in the country who were in prison at the time,” she said. “They’re still in prison, and that means that there’s no one in the country who’s able to speak out and hold the government to account for anything.”

The upcoming COP29, scheduled for Nov. 11 to Nov. 22 in Baku, Azerbaijan, will be the third consecutive climate summit hosted by an authoritarian regime with a poor human rights record. That is a big problem, Harrison said, because “human rights are essential for what is trying to be achieved at U.N. climate talks.”

“We all need these rights to be in place so we can all hold our governments to account for the actions they take, or indeed, actually fail to take,” she said. And it’s not just the law, she added. Science assessed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change recognizes that “equity, social justice, climate justice and rights-based approaches and inclusivity lead to more sustainable outcomes … and support the transformative change we need to advance climate resilient development.”

Open civic spaces for environmental advocates, human rights defenders and indigenous peoples are critical because, she said, “their voices bring their knowledge, their lived experience, to bear, both on climate negotiations and also at the local level.”

The Bonn talks also failed to make much progress toward the important goal of setting a new global target for climate financing, which faces a deadline at COP29 in November. The stalling of that process is not coincidental with the difficulties developing nations have had participating, said Lien Vandamme, a campaigner with the Center for International Environmental Law, because climate justice is at the heart of the finance issue.

The climate crisis is “more than just an emissions problem,” she said. “Climate justice is about people and their rights.The endless pursuit of economic interests of wealthy countries and their polluting industries is causing harm to communities which have done nothing to cause the crisis.”

At Bonn, wealthy countries once again refused to talk about the trillions of dollars developing countries need to adapt to global warming impacts and for a just transition to a safe climate future.

“That demonstrates how far away we are from true justice, and blocked any progress in Bonn,” she said. “The only way forward out of this impasse is for wealthy nations to show up in Baku ready to pay up for what they owe.”

Azerbaijan Persecutes Activists and Journalists

Host countries for the climate summits are decided in rotation among five regional groups in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: African States, Asian States, Eastern European States, Latin American and the Caribbean States and the Western European and Other States.

Russia’s influence tainted the selection process for this year, because Vladimir Putin wouldn’t agree to have any of the other countries in the Eastern European region host due to their support for sanctions against Russia in response to its invasion of Ukraine.

Calls to reform the selection process grew louder after the Baku decision because of Azerbaijan’s very poor human rights record.

“It’s concerning that, by the time Azerbaijan hosts COP29, there may not be any independent, impartial civil society left (in that nation),” said Arzu Geybullayeva, a research consultant with Human Rights Watch. The country has never been a bastion of freedom and there has been a massive new crackdown since last summer, she added.

“We’ve seen arrests on bogus charges of political and civic activists, labor rights activists, journalists and human rights defenders,” she said, after documenting the roundup of more than 20 journalists since last November, when the COP29 decision was announced. The journalists are both from well-known and established opposition outlets, as well as smaller regional media platforms, and many face fabricated smuggling charges.

The crackdown started before the announcement that Azerbaijan will host COP29 and continued in the runup to a snap presidential election held last February, which took place “in an environment of impunity, fear, intimidation,” Geybullayeva said. Main opposition parties boycotted the vote and official international election observers said the vote lacked genuine pluralism.

There is currently a push for new parliamentary elections in the country that could come about around the same time as COP29, which could raise additional security concerns for the climate talks if any violent unrest flares up in connection with the voting.

“The situation puts everyone who is involved in civic space and civic work in potential danger and at risk,” she said, adding that there are only a handful of environmental advocates in the country who all “tread very carefully.”

And at this point, civil society groups have no idea how they will be treated at COP29 because important details of the conference arrangements are still secret, despite the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’s promise to make the hosting agreement with Azerbaijan public.

Last year, the UNFCCC updated its protocols for intergovernmental agreements and “Those conclusions had strong language about the need for the respect for human rights in and around all UNFCCC meetings,” Harrison said. “And it reiterated the need, and encouraged host country agreements to reaffirm commitments to human rights and to the principles of the U.N. Charter. And that in the interest of transparency, host country agreements should be made public.”

Civil Society Resists Authoritarianism

For social scientists that have been documenting links between fossil fuels and authoritarianism, COP29 in Azerbaijan may provide fertile new ground to study.

The oil and gas industry provides most of the government’s revenues, Geybullayeva said, adding that last April, Azerbaijan President Ilham Aliyev said his country’s fossil fuels were a gift from God during his announcement of an expansion of their production.

Most of the increased output is intended for European Union markets, she said, adding that a deal to double fossil fuel exports from Azerbaijan to the EU was finalized in 2022, ahead of the decision to hold COP29 in Baku. Aliyev has positioned Azerbaijan as defending the right of other fossil fuel-rich nations to continue investments and production, she said, “because the world needs it.”

With the recent intimidating crackdown on environmental defenders in Azerbaijan, “it is hard to see how any local environmental group or journalists can effectively hold the government to account for domestic climate policies,” she said.

“The potential chilling effect of the state’s response to the few instances of climate activism cannot be underestimated,” she said. “Who dares to speak up against the fossil fuel industry under these conditions when the Azerbaijani oil and gas industry provides most of the government revenues?”

For now, it’s unclear whether Azerbaijan will tolerate any form of public activism during COP29, and that does not bode well for ambitious climate action, she said, encouraging the international community to exert pressure on the Azerbaijani government.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

“Press the host to allow civil society to demand and scrutinize climate action before, during and after the conference,” she said. “Press the host government to ease its grip on civic space and respect its human rights obligations by upholding the rights to free expression, association and protest.”

She said other countries should insist that Azerbaijani authorities immediately and unconditionally release all those arbitrarily detained for exercising their right to free expression ahead of COP29. And they should emphasize the importance of a thriving and independent civil society to “press the government of Azerbaijan publicly and privately to respect its human rights obligations and immediately and unconditionally release arbitrarily detained journalists, activists and human rights defenders.”

She also said the host country agreement should be made public immediately and scrutinized to ensure that it complies with international human rights law. In the longer term, she said selections of future COP hosts should include human rights criteria, which is a “precondition to ensure ambitious climate outcomes.”

“Without the full and meaningful participation of journalists, activists, human rights defenders, civil society, youth groups and Indigenous people’s representatives, COP29 is much less likely to deliver on the Earth and climate action the world so desperately needs,” she said.