Halfway towards the Atlantic Ocean, South Carolina’s Edisto River flows through the tiny neighborhood of Canadys and past a shell of a retired coal-fired power station. This month that long-shuttered power plant was resurrected as a key to South Carolina’s energy future when the state’s Public Service Commission approved two utilities’ plans to work together on its transformation into one of the nation’s largest gas power stations.

Dominion Energy and state-owned Santee Cooper propose the Canadys plant as a pivotal part of their “reliable, affordable and increasingly clean energy” portfolio as the utilities attempt to wind down burning coal. Environmental lawyers and advocates describe the commission’s approval as a rubber stamp on the utilities’ gamble toward a regional gas buildout, at the expense of more investment in renewable energy sources like solar.

Canadys was closed in 2013, and South Carolina’s use of coal power has more than halved since then. Four plants still operate but, by 2030, only one will remain open, according to Dominion and Santee Cooper, also known as the South Carolina Public Service Authority. As yet, there are no plans to close the fourth and largest coal plant operated by Santee Cooper. But both utilities, for months, have been wrangling over how best to provide future reliable energy for their nearly 3 million in-state customers.

We’re hiring!

Please take a look at the new openings in our newsroom.

See jobs

“We are really at a key transition point in South Carolina and the Southeast,” said Kate Mixson, a senior attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center, a nonprofit based in Charleston. “All our utilities are trying to shutter their now very old, very expensive coal plants and the question is: what do you replace those with?”

According to the utilities’ Integrated Resource Plans — mandatory regulatory filings that the commission must approve every three years — Dominion and Santee Cooper propose they join forces to create a huge combined-cycle power plant at Canadys, scheduled to operate by 2031. The plant would provide up to four times as much energy as the former coal plant, according to their plans.

Dominion’s IRP was approved in November and a vote on Santee Cooper’s followed on Feb. 14. Now Santee Cooper is seeking legislative approval for the joint venture. Two separate bills are under discussion in the General Assembly: a Senate bill that “encourages” the utilities to build at Canadys and a House bill that states a gas plant at Canadys is in “the public interest” and adds some notable restrictions on how such conversions are reviewed.

The House bill proposes weakening oversight of new power stations that are “replacing” old facilities, and it seeks to reduce the Public Service Commission’s membership by more than half, from 7 to 3 positions. Current state law requires the commission to approve any new energy facility. The House bill would allow utilities — without commission review — to replace retiring plants with what it defined as “like facilities.”

Mixson described the bill as creating a loophole for energy companies to skirt hard questions. The bill would restrict reviews of “any facility that represents the rebuilding … rerouting … increasing … or otherwise reconfiguring of an existing transmission line or other transmission facilities including, without limitation, projects to increase the capacity of such facilities.”

“It would effectively hand over the keys to the utilities,” Mixson said of the potential change. The rule would be “opening the door for them to make bad investments, while at the same time allowing them to rush past environmental review.”

The bill was sponsored by half of the House’s members, including seven Democratic representatives. Rep. Marvin Pendarvis, a Democrat representing Charleston, described his vote to Live 5 TV News as helping South Carolina reach “a place where we’re going to be able to fulfill the energy needs of our state.”

The Canadys gas proposal has been criticized for months by environmentalists who contend the state has an opportunity — amid the coal transition — to reduce or eliminate fossil fuel consumption. The Southern Environmental Law Center presented a renewable energy proposal to the commission that contended the state could meet its energy needs by first pursuing solar and battery use and, by the end of the decade, adding wind power.

Santee Cooper’s IRP was reviewed by an outside consulting firm, which suggested the state wait on the gas conversion plan and take a “hybrid” approach to provide energy resiliency. The report, commissioned by state regulators, was produced in December by PA Consulting, a London-based firm. It found that Santee Cooper’s plan “largely presents a viable, prudent roadmap” but had made the gas plant conversion a “foregone conclusion.”

The PA Consulting report emphasized the state-owned utility should consider alternate sources of energy, and it recommended the commission “withhold any approvals for the proposed gas facility.” It also recommended that Santee Cooper avoid any binding financial commitments with Dominion regarding the gas plant conversion.

The Public Service Commission would not respond to questions about the PA Consulting report or explain why the commission did not follow the consultants’ recommendations.

A review of documents and testimony submitted by both utilities, however, indicate what regulators weighed.

Santee Cooper’s Manager of Resource Planning Franklin Settle testified to the commission that the utility performed “rigorous analysis” of “all relevant technology alternatives.” The company attempted various models of how to meet the state’s energy needs, he said. Unless “new fossil fuel resources were intentionally excluded,” every model “chose” a large gas plant as the top option.

Dominion, in response to questions from ICN, said its modeling led to the same conclusion. “A “large, highly-efficient gas-fired” plant was the “optimum replacement for remaining coal generation” recommended to Dominion, the company said in a statement.

By 2040, Santee Cooper and Dominion plan to add a total of over 3000 megawatts of renewable energy generation each, according to their IRPs. But they would still be relying on coal and gas as well. Santee Cooper’s generation will be based on 30 percent renewable and 61 percent from fossil fuels by 2040. Dominion indicated that at least 59 percent of its generation will be through renewable sources by 2050.

Santee Cooper’s spokesperson Mollie Gore said the gas plant was necessary to provide resiliency in the state’s overall energy landscape.

“Solar only produces power when the sun is shining, right? It doesn’t produce anything at night, doesn’t produce anything during thunderstorms,” said Gore in an interview with ICN. “It gets pretty hot down here in August, and we need something that can ramp up and ramp down quickly.” Santee Cooper currently has no battery storage, Gore said. “We’re frankly waiting for costs to come down and technology to continue to improve.”

Mixson said Santee Cooper’s calculations underestimate current battery technology and “arbitrarily slow-walks” the state’s solar potential. Other advocates warn that the utilities’ plans underestimate or ignore some risks that could mean higher prices for consumers.

To Eddy Moore, an attorney with the Charleston-based Coastal Conservation League, the utilities’ plans to build big at Canadys ring familiar.

In 2008 Santee Cooper and South Carolina Electric and Gas (now owned by Dominion) tried to reduce coal reliance another way: with nuclear power and specifically a proposal to build two costly reactors at the Virgil C. Summer station near Columbia. The plant was never finished because of billions of dollars in cost overruns, and rates were increased as a result of what is now known as “Nukegate.”

“There’s a huge sense of deja vu,” Moore said about the Canadys proposal before the legislature. “This is the next nuclear cost overrun.”

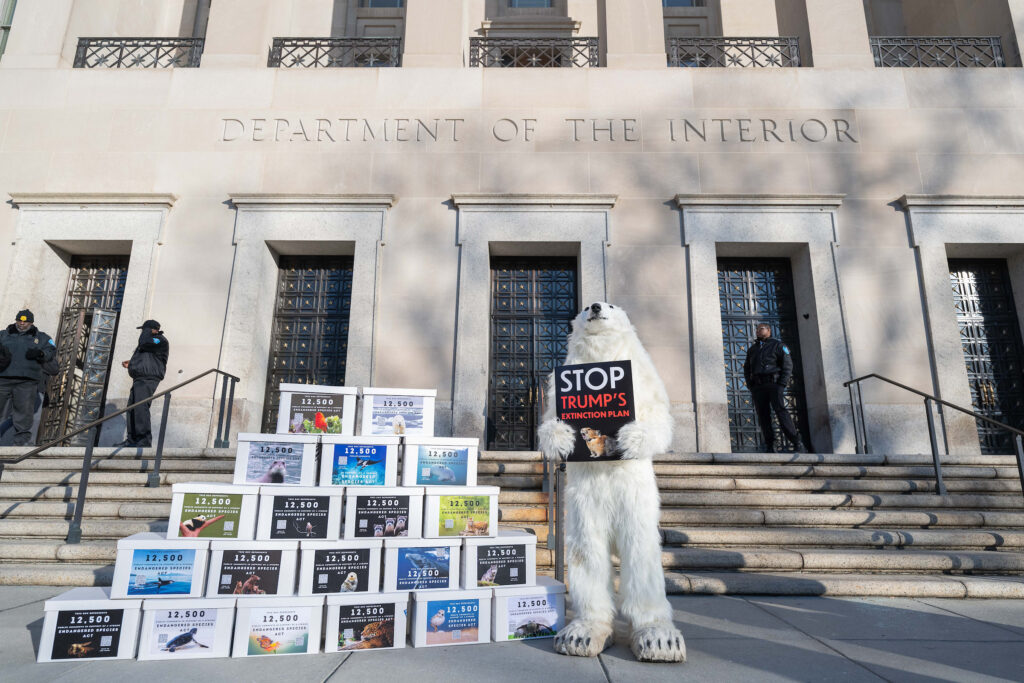

Moore said that combined-cycle power stations are relatively easy to build in contrast to nuclear plants. But construction costs could rise as the utilities seek permits to lay miles of new pipe to transport gas into the plant. Gas plants will also likely face new federal pollution limits this decade, including rules expected in April that impose heightened restrictions on all fossil-fuel power stations and specific emissions rules for combined-cycle plants like the one planned at Canadys.

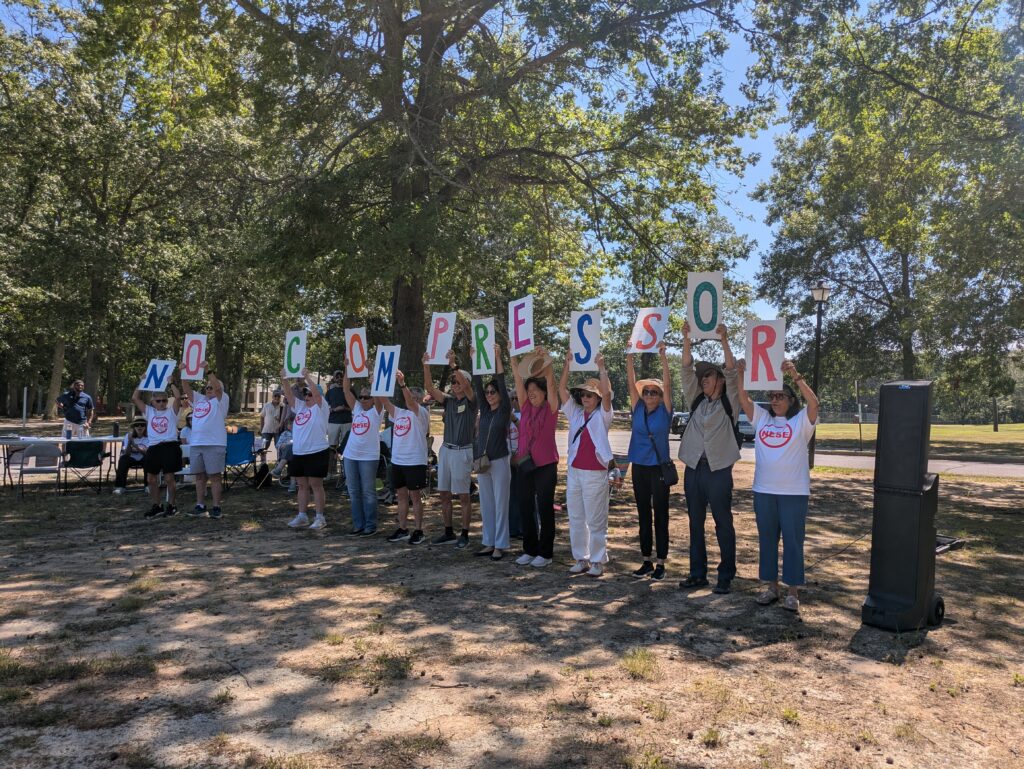

Both utilities acknowledge the converted plant would require new interstate pipelines. Gore said Santee Cooper would not share potential pipeline routes because they had not yet been finalized. She did not say when the potential routes would be made public, but she promised “everything involves using existing right of way.”

Moore said he was skeptical. “The recent history of the construction of interstate pipelines is filled with delays and huge cost overruns,” a fact which Dominion also acknowledges as a “principal risk” in its IRP. If pipelines were delayed, Dominion said in its IRP, plans to end coal use could be also delayed..

If the plant at Canadys was delayed even one year — by pipeline permits or otherwise — it would violate new pollution standards drafted last year by the Environmental Protection Agency.

The EPA rules, some that are still being finalized, note the potential carbon emissions at gas plants like the one planned for Canadys. If the plant runs over 50 percent of its capacity — which both utilities plan to in their IRPs — then the companies would have some costly problems, Moore said.

Santee Cooper and Dominion would be left with three choices, he said. They would have to capture 90 percent of Canadys’ carbon emissions by 2035 or blend almost a third of their fuel with lower emissions hydrogen by 2032, going almost completely hydrogen powered by 2038. The more likely scenario is the utilities would have to operate Canadys under 50 percent capacity to avoid the regulation altogether, he said.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

“We don’t know what the final rules will be, but the draft rules say, if you had to boil down 400 or 500 pages to one sentence: don’t build a combined-cycle plant,” Moore said.

“When you add all of those things” — potential regulations, interstate pipeline permit delays and the volatility of gas prices — “you basically come out with the same multi-billion dollar cost risk that we experienced with the nuclear plant,” he said.

Santee Cooper’s IRP does not address the draft rule that could affect Canadays, but it estimates potential costs of up to $13 billion related to federal “policy that would impose on utilities additional costs related to CO2 emissions.” Gore told ICN that Santee Cooper would address the EPA rules’ impact “if there is a final rule issued in the next few months.”

With the deregulation attached to Canadys’ approval, both Mixson and Moore see a door opening for a gas buildout across the region. Last month, another utility, Duke Energy, based in North Carolina and which operates in several states, revised its IRP to add plans for a new gas plant in South Carolina.

“It’s not really just a story about Santee Cooper and Dominion or the South,” Moore said. “It’s the gas industry trying to push to get these multi-decade multi-billion dollar revenue streams that are up for grabs between the gas industry and the renewable industry.”